What the Word “Beauty” Meant to Helen Frankenthaler

Douglas Dreishpoon on the Reflections of an Iconic Artist

Helen Frankenthaler never questioned why she painted or for whom. Expressing herself through art was something she had done since childhood. Making art channeled her emotional energies, kept her focused, stable. Being a committed artist meant finding ways to accommodate external concerns, knowing full well that the world outside the studio would never be the world inside, where one fearlessly confronts angels and demons head-on.

Seeing the process of painting as perpetually in flux enabled Frankenthaler to see the medium of painting as perennially relevant—a mounting challenge as the 1960s rolled into the1970s and 1980s and a critical mass declared modernism moribund.[1] As the death toll from AIDS escalated, with more and more artists mobilizing in the streets, Frankenthaler’s solitary studio practice, dedicated to abstraction and the pursuit of beauty, seemed to many solipsistic, out of step.

With a raging epidemic claiming the lives of countless individuals, any retreat to rarefied aesthetics could be construed as reactionary.[2] But beauty defies simple definitions, binary differences, and art-historical distinctions. Go back to John Ruskin’s second volume on Modern Painters, to the chapter “Of False Opinions Held Concerning Beauty,” or re-read Dave Hickey’s provocative essays on the same subject, to understand how nuanced the word is.[3] Beauty may well boil down to a state of ideational grace untainted by outside influences, a creative urge transcending fickle politics and party affiliations.

The novelist Toni Morrison, in a 1992 interview with The Paris Review, a year before she received the Nobel Prize in Literature, advocated for beauty “as an absolute necessity. I don’t think it’s a privilege or an indulgence,” she urged. “It’s not even a quest. I think it’s almost like knowledge, which is to say, it’s what we were born for. . . . I don’t think we can do without it anymore than we can do without dreams or oxygen.”[4]

What did beauty mean to Frankenthaler? “Today,” she told Voice of America correspondent Susan Logue Koster in1993, a day after her sixty-fifth birthday, “there’s a fashion in the art world where the word beauty is ostracized as being obsolete, meaningless, and that other considerations in art are far more important. Beauty is a very tricky word, and the way I use it means an order and a sense of rightness that moves you and that usually has to do with the scale, and the light, and the tradition, and everything else that goes into a painting.”

Like the myth of the Matissian armchair, Frankenthaler’s vision of beauty reflected the depths of a human condition.

Four years later she said to curator Julia Brown: “All beautiful painting has a sense of necessity and urgency, as if it were imperative that the artist make this work, that it had to be born. The painting becomes a means of expressing one’s inner gift. It is a catharsis.”[5] Beauty had many faces. Some were light, others dark. Some were raw and unhinged, others full of grace. Whatever its significance, beauty’s representation was never superficial. Like the myth of the Matissian armchair, Frankenthaler’s vision of beauty reflected the depths of a human condition. Still, her persistent use of the word, particularly during such a politically fraught period, made her (and the work) vulnerable.[6]

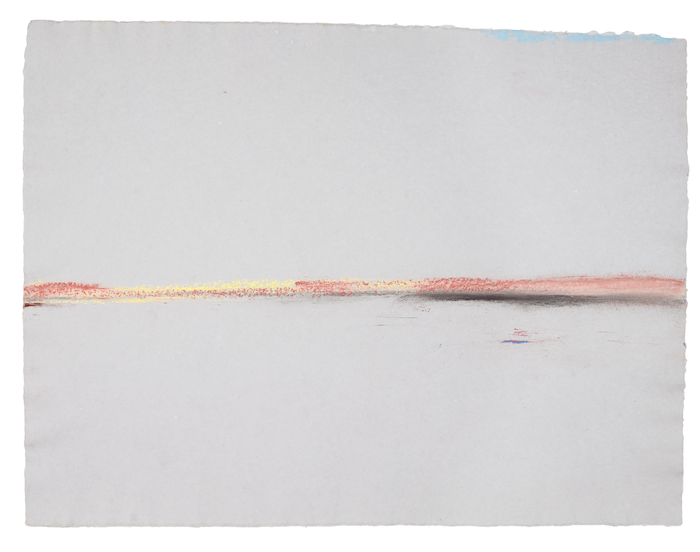

© 2022 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; plate 73, Untitled, 2003, pastel on paper. 18 × 23 ½ inches (45.7 × 59.7 cm)

© 2022 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; plate 73, Untitled, 2003, pastel on paper. 18 × 23 ½ inches (45.7 × 59.7 cm)

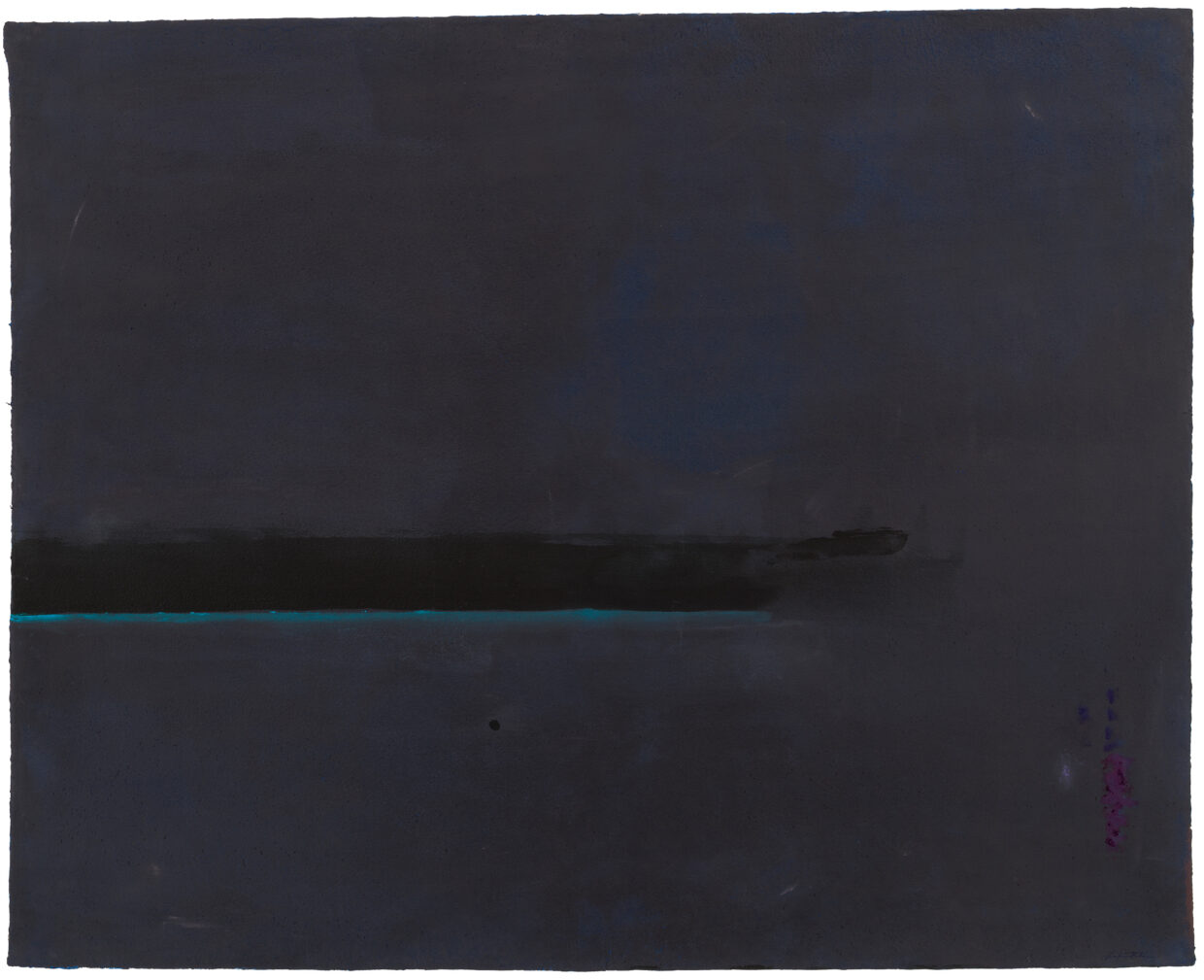

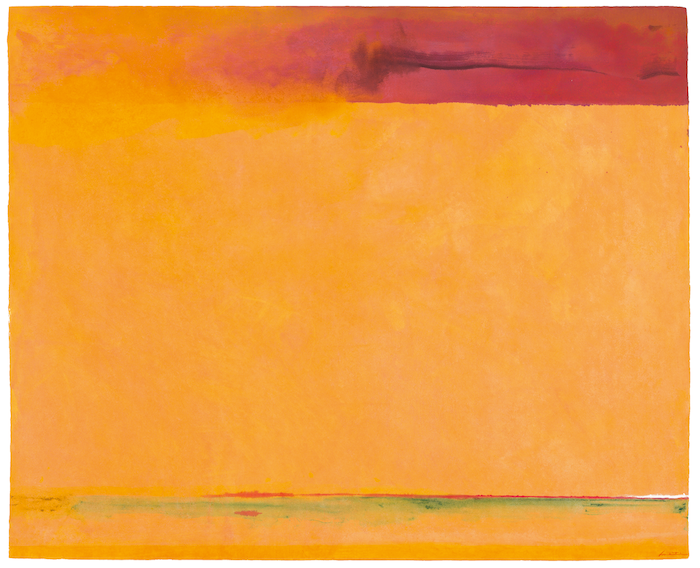

Though at times dispirited, she courted beauty, in the studio more than anywhere else, as she rose to the occasion, time and time again, to paint. Blessed with memorable encounters, a vast art-historical image bank, and technical prowess, the artist moved in whatever direction suited her mood and imagination. Some of the most poignant late works, conceived as minimal pastel horizons (Untitled, 2003, plate 73), or as acrylic trails dissipating into silent space (Southern Exposure, 2002, plate 67), feel like veils of time fleeting. In works bearing titles like Almost Dark, Ebbing, The Other Side, and Port of Call (all 2002, plates 65, 69, 64, and 63), one senses a glimpse of finality. Looking at Driving East (2002, plate 66), it’s hard to know whether the flickering light along the horizon is ascending or descending. Is it dawn or dusk?

© 2022 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; plate 63. “Port of Call,” 2002; acrylic on paper. 60 × 74 ⅞ inches (152.4 × 190.2 cm)

© 2022 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; plate 63. “Port of Call,” 2002; acrylic on paper. 60 × 74 ⅞ inches (152.4 × 190.2 cm)

© 2022 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; plate 67

© 2022 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; plate 67“Southern Exposure,” 2002; acrylic on paper. 60 ½ × 73 ⅞ inches (153.7 × 187.6 cm)

Approaching artistic lateness is inherently complicated. “Does one grow wiser with age?” Edward Said asks in On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain, his own swan song. “And are there unique qualities of perception and form that artists acquire as a result of age in the late phase of their career?” Said accepted the “notion of age and wisdom in some last works that reflect a special maturity, a new spirit of reconciliation and serenity often expressed in terms of a miraculous transfiguration of common reality.” But he also recognized another dimension of artistic lateness, “not as harmony and resolution but as intransigence, difficulty, and unresolved contradiction.”[7] Both tendencies, evident in Frankenthaler’s late works, had been there from the start.

There’s every reason to be philosophical about growing old. Simone de Beauvoir clearly understood the realism of aging as she herself crossed the midlife threshold and wrote The Coming of Age. Could it be that artistic creativity (visual, literary, musical, theatrical, filmic, choreographic) is one of the last bastions where any individual, regardless of their age, can still impact the cultural realm? “Like all human conditions,” De Beauvoir proposes in the book’s preface, “[old age] has an existential dimension—it changes the individual’s relationship with time and therefore his relationship with the world and his own history.”[8]

Frankenthaler’s own history was paced by intimate friendships, nurtured and sustained. “I suppose the older we get the more we appreciate the continuity of friendship—the fortunate gift of sharing the present with the nostalgia,” she wrote to the sculptor Anthony Caro.[9] Her closest friends had always been a sounding board for ideas and feelings, fears and conundrums. Her letters and notes to Caro, painter Grace Hartigan, author Sonya Rudikoff, and sculptor Anne Truitt, honest and heartfelt, reveal the challenges each of them faced at this point in their lives. “I think the older we get the longer it takes to rally, in many ways—and a different set of fears hangs over us,” she admitted to Rudikoff.[10] Whatever her physical and emotional challenges, and there were many during the last decade of her life, the painter remained committed to art and to the people who mattered to her. “Over time, we’re left with the best” was how she summed up her pursuit of an art unencumbered by rules. At that moment, nearing the end of her candid conversation with Brown, there was no reason to believe otherwise.

*

[1] Painting’s contested place in a postmodern discourse played out prominently in journals and exhibition catalogues (see Douglas Crimp, “The End of Painting,” October 16 (Spring 1981), 69–86; and Yve-Alain Bois,“ Painting: The Task of Mourning,” Endgame—Reference and Simulation in Recent Painting and Sculpture (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1986), 29–49). For a nuanced account of painting’s perennial hardships, see Katy Siegel and David Reed, High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting, 1967–1976 (New York: Independent Curators International, 2006).

[2] Such were the optics, during the culture wars, around Frankenthaler’s association with Hilton Kramer and The New Criterion, a conservative organ for writers railing against art’s multicultural incursion into politics.

[3] John Ruskin, “Of False Opinions Held Concerning Beauty,” in The Complete Works of John Ruskin in Twenty-Six Volumes, Modern Painters(Philadelphia: Reuwee, Wattley & Walsh, 1891), 253–62; and Dave Hickey, The Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty (Los Angeles: Art Issues Press, 1993).

[4] Toni Morrison to Claudia Brodsky Lacour, Princeton University,1992, accessed in “Episode 13: ‘Before the Light’” podcast, October 23, 2019, https://www.theparisreview.org/podcast/6047/before-the-light.

[5] Frankenthaler’s conversations with Julia Brown, in New York and Connecticut, during the spring and into the fall of 1997 appear in the publication that documents the exhibition After Mountains and Sea: Frankenthaler 1956–1959 (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1998), 27–47.

[6] Frankenthaler’s defense of beauty and quality, as criteria for determining artistic merit, had rippling consequences during her tenure(1985–1992) as the sole visual artist on the National Council on the Arts; see Michael Brenson, Visionaries and Outcasts: The NEA, Congress, and the Place of the Visual Arts in America (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 115–120.

[7] Edward W. Said, “Timeliness and Lateness,” On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain (New York: Pantheon Books, 2006), 6–7.

[8] Simone de Beauvoir, The Coming of Age, translated by Patrick O’Brian (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1972), 9. The book was published (in French in 1970) when De Beauvoir was sixty-two years old. In it she advocates for the aged in the same empathetic way she advocated for women decades earlier in The Second Sex (1949).

[9] Helen Frankenthaler letter to Anthony Caro, June 18, 2000, Helen Frankenthaler Foundation Archives, New York.

[10] Helen Frankenthaler letter to Sonya Rudikoff, September 23, 1990, Sonya Rudikoff Papers, Manuscripts Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Helen Frankenthaler: Late Works, 1988-2009, with a preface by Elizabeth Smith, text by Douglas Dreishpoon and Suzanne Boorsch, and roundtable with Katharina Gross, Pepe Karmel, and Mary Weatherford. Available via Radius Books.

Lead image: Helen Frankenthaler working on Untitled (1991) in her Saddle Rock Road studio, Shippan Point, Stamford, CT, July 1991. Helen Frankenthaler Foundation Archives, New York. Photograph by Vincent Dion.

Douglas Dreishpoon

Douglas Dreishpoon is director of catalogue raisonné at the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, chief curator emeritus at the Buffalo AKG Art Museum, New York, and consulting editor at The Brooklyn Rail. His anthology of sculptors’ writings, Modern Sculpture: Artists in Their Own Words, for the Documents of Twentieth-Century Art series (University of California Press) is forthcoming this fall. An art historian-curator in musician’s clothes, he holds a PhD from the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.