On Phone Sex, First Writing Jobs, and Unexpected Teachers

Lynn Melnick Learns Some Early Lessons About Persistence

When I was not in the 11th grade because I had stopped going to school, I took an equivalency exam and enrolled in community college. Because I’d failed so spectacularly at high school, I hadn’t learned much after 8th grade. Even when I showed up, I was in the principal’s office a lot, or I was smoking in the girl’s room, or I was giving blow jobs in the back of the dark auditorium. So it wasn’t that I wasn’t busy; I just wasn’t learning grammar or the structure of an essay.

Community college was $5 a credit in California back then, plus the cost of books. I signed up for two classes my first semester: an intro comp class and poli sci. I went to the campus bookstore and bought two college-ruled notebooks, one in pink and one in purple. Pink was for the comp class. “Santa Monica College” was embossed on the front of each.

The Big Blue Bus down Pico Boulevard in Los Angeles was 50 cents in 1990 and after I enrolled at school, not far from the ocean, I took the bus east and more east and then transferred to another line and ended up downtown in a ramshackle office building where I held a part time job at a phone sex line.

The ad for phone sex workers had promised $9/hour, which was obscene; the minimum wage at the time was $4.25. On impulse a few weeks earlier, I had called them from a pay phone somewhere in Hollywood and a brusque man with a heavy Slavic accent gave me the office address.

The office was a big square and stunk like wet fiber because there was a leak from the roof and a perpetual damp stain on the industrial carpeting. There were about a dozen women spread around the periphery and they were their own little factory of movement. One woman was bouncing up and down in her chair panting. Another was knitting. Lisa always had her schoolbooks with her, and sometimes her kids.

No one looked up when I came in. I panicked and almost left but then John, the owner, emerged from the only separate office. He was a portly white man with a face that completely changed when he smiled. He sweat a lot, wore mostly brown suits, treated everyone at the office with a genuine respect I don’t think many of us were used to.

He took out a pen and marked up where I needed to slow down, what details would improve the story, and how to hold tension until the (literal) release at the end.I totally flunked phone sex. I was horrible at it. I was so shy and couldn’t figure out how to coordinate each man’s desire to the things he wanted to hear to get off, and I couldn’t remember what sounded like what—how many fingers to suck to sound like a dick or how hard to clap to sound like a spank. I became so overwhelmed and embarrassed, I cried. John felt sorry for me and asked me if I could write. Yes, I nodded, though I hadn’t done much of it. I didn’t tell him I wanted to be a poet. He told me he had a job writing scripts that would be recorded for people who called in and were too shy for a live girl, or who didn’t want to pay for a live girl. He told me if I could get his dick hard with my script, I could have the job. He set me up at an empty desk near the carpet stain.

I wrote a script about a man sitting alone in a movie theater who is interrupted by a beautiful woman who miraculously wants to sit on him. I showed it to John, and he took out a pen and marked up where I needed to slow down, what details would improve the story, and how to hold tension until the (literal) release at the end. He crossed out several superfluous sentences. Callers won’t care what color the seats are, he said. The whole paper was a mess of edits, but he gave me the job anyway.

It was the first writing job I would have. John said he could pay me only $7/hour, which was still a ton of money, and it was in cash. I sat at the desk near the stinky carpet drip, in the middle of the room, far enough from everyone else and the cacophony of phony fucking sounds, and I wrote scripts: missionary sex, butt sex, group sex, lesbian sex, oral sex, rape, bondage, mind control, feet. I made up what I hadn’t experienced, or I asked the women in the office. Anitra had been a dominatrix and gave me some tips. Lisa coached me on where to place stage directions for sex sounds.

I got used to the work like any other job, and I was happy there and proud of my scripts, but I didn’t tell many people about it. It was cordoned off, another part of my life. I was trying to turn my world around.

I’d been working at the phone sex line for a few months already when I started Hari Vishwanadha’s Reading and Composition 1 class at Santa Monica College. The purpose of this intro course was to learn to outline, draft, and revise an essay. Mr. Vishwanadha seemed middle-aged but was probably under 40. He was thin, wore shirts with buttons but with the sleeves rolled up. He had a thin moustache and spoke quickly. He was stern and yet somehow also gentle.

After we got our term paper assignment—seven to pages on the subject of our choosing—I walked over to the library to find something to write about. I wish I could tell you how I landed on Civil War photography as my research essay topic, but I have no memory of the process. I had no particular interest in the Civil War or the portrait photography of lauded and long-dead men. Maybe it seemed like a real capital-T Topic. Maybe there was such an endless amount of information my research would be easier. Maybe I opened the catalog to Matthew Brady and grabbed those books before catching the bus down Pico to write phone sex scripts.

I have held many jobs and written many things since 1990. There are things I know I’ve dashed off and they’ve been beloved. There are things I’ve labored over and it showed and those I labored over and it didn’t. But I honestly don’t think I have ever worked harder on any piece of writing than I did on that paper for Reading and Composition 1. I typed and retyped. I spent hours in the library lugging big jacketless books around, clutching them to my chest and then thudding them into a cubicle to get one more fact, one more perspective. I spent hours transcribing the paper from my scribble on pink paper to a perfectly typed document. I didn’t have eraser tape; I started over every time I made a mistake.

I knew Mr. Vishwanadha’s office hours well. I’d had him approve my essay topic and outline, my first paragraph, my general vision for the paper. I turned it in at the 10-page maximum. Do you know that feeling where you just feel so high after doing a thing you love and doing it well? I felt that.

I got a B-.

I picked up the paper from the stack in Mr. Vishwanadha’s mailbox in the English office and a wave of dizziness made me reach for the wall. I signed my name at the top of his office hours sheet and sat on the linoleum in the hallway. While I waited, I edited phone sex scripts. I’d learned to make them leaner, to create tension in fewer words, to hint at the excitement around the corner without blowing the whole wad at once. John would suggest edits in the interest of perspective; he often thought the men should be treated more manly. The women in the office were sometimes bored enough to offer me their ideas, too, which were spot on due to their lived experience of taking the sex calls. “RIP HER CLOTHES OFF,” Anitra had written in all-caps on the top of one of my scripts. Most of the girls kept cloth to rip in their cubicles. Okay! I ripped her clothes off.

I channeled that girl in the hallway at Santa Monica College: a little defeated and yet sure she could do better.Mr. Vishwanadha showed up at his office, on time as ever, and I took out my pink notebook and sat down in the chair beside his desk. He was disappointed too, he said. As a writing teacher now, I understand his empathy was genuine, but at the time I didn’t know if I could believe it. We went over edit ideas. He showed me where I had failed to back up assertions with proof. He complained that I spent too long describing the photos rather than the history and importance of the photos. He good-naturedly laughed at some very bad sentences.

Try again, he gently prodded. I will revise your grade accordingly, he said. Meanwhile, I gave serious thought to quitting school. I’d been offered a better job at the phone sex company, chatting with men who didn’t want sex talk, but were just lonely and wanted to chat. It paid $8 an hour.

I typed my final revised draft of the Civil War photography paper on the phone sex office typewriter because my own was broken. I told Lisa and Anitra that if I didn’t get an A on the paper, I would quit school and double my work hours. Lisa called me a dumbass white girl, which I was. I had no idea how many chances I’d had to rise from the seedy underbellies in which I had found myself as a teenager. No idea. I had no idea how privileged I was to have had a K-8 education that taught me enough that I could survive college while having skipped most of high school.

Mr. Vishwanadha gave me an A- on the revised paper, and an A in the class.

I stayed on at my phone sex office job for only a few more months. I didn’t mind writing the scripts, but I was running out of ideas and starting to imagine a life for myself that didn’t leave a knot in my stomach. I joined the Scholar’s Club at Santa Monica College, took a job tutoring other students in the writing center in the library on campus, and turned 17. I made $5.85 an hour, on the books, and I felt great. I used all the tricks that John and Mr. Vishwanadha had taught me about outlining and pace and supporting details and when my students became frustrated with all my pen marks on their papers I told them, this is a sign of your eventual success.

I have now spent my life thinking about writing and being a writer, and many years teaching writers. Those early lessons I got on craft—from likely and unlikely sources—have stayed with me through every essay, every editing job, every student manuscript, and through to writing my memoir. Having spent most of my writing life as a poet, I didn’t know if I could write a whole book of prose, but it was exhilarating to try, to be at the beginning again. I channeled that girl in the hallway at Santa Monica College: a little defeated and yet sure she could do better. I just kept at it until I got it right.

__________________________________

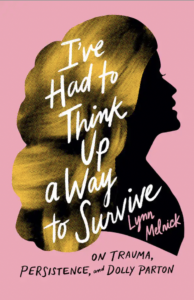

I’ve Had to Think Up a Way to Survive: On Trauma, Persistence, and Dolly Parton by Lynn Melnick is available via University of Texas Press.