What the Toxic Morality of Crowdfunded Healthcare Says About American Society

Nora Kenworthy on 21st-Century Patchwork Solutions to Persistent Social Inequality

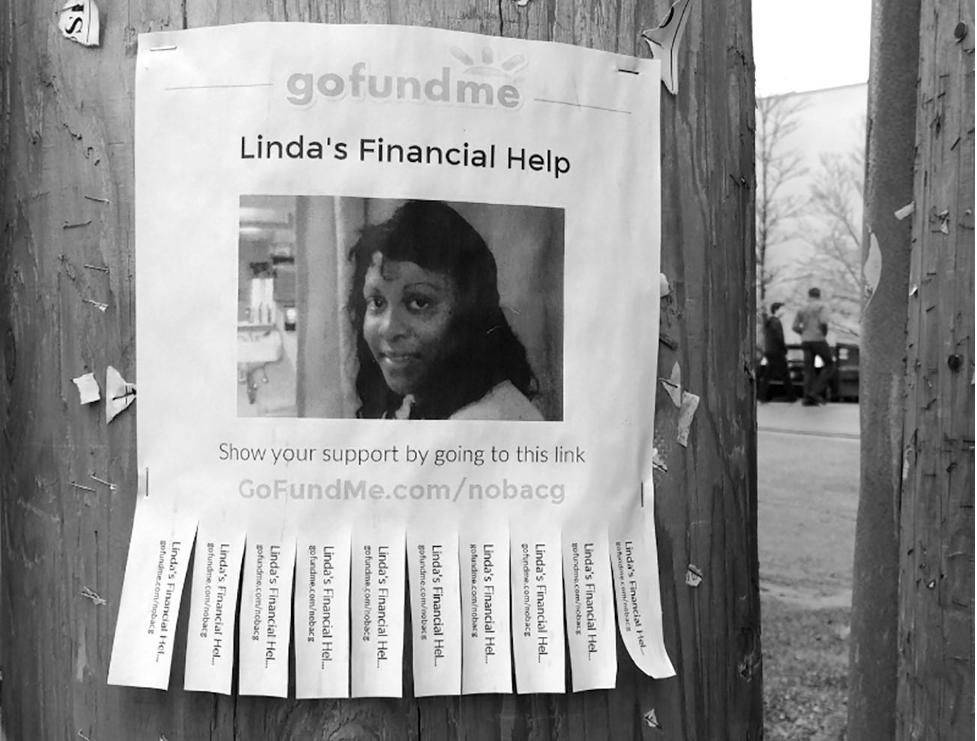

The first time I saw a medical crowdfunding campaign, it was in the form of a flyer posted to a telephone pole in Seattle. At the time, in 2014, people who started a GoFundMe were provided with a printable flyer they could circulate since the site had little name recognition. Much like dog walking or babysitting flyers, the tear-off tabs at the bottom directed passerby to a campaign’s web address.

At the time, it reminded me of an electronic version of the donation jars I often saw in grocery and convenience stores for a neighbor’s surgery or cancer treatment. Though the Affordable Care Act (ACA), or Obamacare, had been passed several years earlier, many Americans still went uninsured or struggled with the costs of care that insurance would not cover. Getting sick or injured in America, as many know all too well, is a very expensive business. Crowd-funding offered a way out: an easy digital way to ask friends, family, and strangers for small donations. If enough of them gave donations, you could raise money to pay off bills, afford a much-needed surgery, or have time to recover without going into debt.

Crowdfunding refers to a practice of appealing for donations or investments from large groups of people, typically using online digital platforms. These digital platforms can be grouped into two general categories: entrepreneurial crowdfunding supports business or creative projects, and charitable crowdfunding collects donations that go to individual or collective causes.

There are crowdfunding platforms for supporting artists, helping pay for animals’ vet bills, contributing to classroom supplies for teachers, or even helping underwrite breast enhancement surgeries. But the largest proportion of charitable crowdfunding in the United States seeks donations for health needs. Most commonly, people seek medical crowdfunding to pay off medical bills and debts; to help minimize some of the harms of health emergencies, accidents, and disasters; and to cover the many additional costs that come with illness, such as taking time off work.

Crowdfunding can powerfully reproduce the status quo rather than change the fates of those who are most in need.

Digital crowdfunding sites mostly emerged in the years following the 2008 financial crisis, which marked the beginning of an increasingly precarious economy for citizens in many countries, including Americans. As governments implemented austerity measures to cut back public programs, digital platforms helped usher in new “gig economies.” While pop culture embraced the “hustle and grind” ethos of these new markets, gig economies also limit rights and organizing, make worker struggles ever more invisible, and leave workers less safe, healthy, and protected.

Crowdfunding, while organized for the charitable economy, adopts the same ethos as the gig economy: users have freedom and autonomy, and their success seemingly depends on their ability to hustle, work hard, and outcompete others. But beneath this ethos is a harsher reality: success is rare even for those who work very hard, platforms often exacerbate inequalities, and many are left more precarious than they started out.

Despite these realities, the feel-good veneer of charitable crowdfunding is powerful and has ushered in a meteoric rise for platforms like GoFundMe. Started in 2010, GoFundMe initially grew slowly. But by 2015, founders Brad Damphousse and Andrew Ballester sold their majority stake in the company to investors; at the time the deal was valued at$600 million, and the site had amassed an estimated $1 billion in donations. Two years later, GoFundMe had reached more than $3 billion in donations, generating an estimated $100 million in annual revenue for the company.

By 2019, CEO Rob Solomon disclosed the platform had raised more than $7 billion in donations, and a year later, GoFundMe said it had processed more than $9 billion in donations, from more than fifty million donors. And by 2022, the company reported it had raised more than $17 billion from more than two hundred million donations. Throughout this period of astronomical growth, the company aggressively acquired competitors, edging out nearly all other platforms in marketplaces such as the United States. And it made these acquisitions without publicly announcing further venture capital investment, indicating that it is generating enormous revenue to sustain this expansion.

Along the way, GoFundMe has garnered widespread public recognition, positioning itself at the helm of a dramatic cultural shift in how Americans think about, and practice, charity and help seeking. “We’ve become part of the social fabric in many countries,” Solomon said in 2017. “We’re a part of the zeitgeist. When news events happen in the world, GoFundMe is a big part of the story.” A year prior he had claimed, “if we were a non-profit or a foundation we’d be the fourth or fifth largest nonprofit in the world, and the second largest foundation after the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.”

It is undeniable that crowdfunding has become a major cultural phenomenon. GoFundMe sees charity—what it often calls “the giving space”—as an enormous market for potential profit-making. But as this book will explore, it also seeks to alter how people engage in help seeking and caregiving. Nor does GoFundMe plan to stop there: in 2019, Solomon told a journalist that the company’s “grand ambition” was to ensure that all online charitable donations—whether to individuals or nonprofit organizations—eventually go through the site.

Crowdfunding’s rise to prominence can also be tracked by the exponential growth in money raised by its most successful campaigns. One of the earliest crowdfunding success stories was the “Saving Eliza” campaign, started by parents of a young girl with Sanfilippo syndrome, a rare genetic condition, who were seeking donations to fund research that they hoped would save her life. With the help of compellingly produced videos and ample media coverage, their original campaign raised more than $2 million.

In 2016, Equality Florida started a fund for victims of the Pulse Nightclub shooting, which became GoFundMe’s largest campaign to date, raising more than $4 million in a matter of days. By 2018, Brian Kolfage’s highly controversial “We Build the Wall” campaign to fundraise for President Trump’s proposed wall on the Mexico-US border raised $20 million before becoming embroiled in legal troubles.

In the summer of 2020, as Black Lives Matter demonstrations spread across the United States, campaigns for victims of police violence became some of the highest-earning personal campaigns on the site: the George Floyd Memorial campaign raised more than $14 million. As COVID-19 wracked the United States that year, GoFundMe’s most successful campaign to date raised $44 million: its purpose was to address food insecurity arising from the pandemic.

It sometimes feels that we can trace America’s moments of crisis, trauma, hate, and, sometimes, hope by hopscotching from one viral campaign to the next. But the stories these campaigns tell is only one facet of the realities of crowdfunding. Most of us experience crowdfunding when friends, family, or we ourselves have to turn to it for help. Few of those campaigns go viral. Some do very well, and most earn a modest few thousand dollars. But if we look a bit closer, we see that crowdfunding can powerfully reproduce the status quo rather than change the fates of those who are most in need.

Finally, there is a facet of crowdfunding that most of us will never see or experience: many campaigns are started only to get a few, if any, shares or donations. These campaigns aren’t likely to show up on social media feeds or on the landing pages of GoFundMe’s website. They are a remarkably common, if nearly invisible, phenomenon. During the early months of COVID-19 when a surge of people turned to GoFundMe to seek and give help, nearly half of campaigns got no donations at all. This is the hidden side of the new crowdfunding marketplace.

*

Despite the grim odds of viral success, many people do find that crowdfunding has distinct benefits. For some, it can offer a lifeline to cash that tides them over during moments of serious crisis; for others, the benefits are more emotional than financial. It can offer connection to friends and family, particularly when isolated by illness or its treatment. It can provide an easy way to communicate during health crises, even helping people feel validated or empowered. Some people also told me that it strengthened their relationships with family and friends, deepening ties to social support.

Others found that navigating crowdfunding platforms was far easier than traversing the complicated bureaucracies of the US social safety net. But these experiences sit alongside, and even coexist with, feelings of shame, humiliation, stigma, judgment, and failure when it comes to asking for help online.

Many Americans will say, at first glance, that they think sites like GoFundMe are great. Yet these same people will also express sadness at seeing the many campaigns that go unfulfilled, fears about scammers and fraudulent campaigns, and feelings of ambivalence about who to help and why. My purpose here is not to portray digital crowdfunding as simply good or bad but to explore the complexities of how it has embedded itself in our contemporary lives and social support systems, and examine the impacts of its ubiquity, both for individual users and for society at large. Nor am I solely interested in the experiences of influencers or highly visible campaigners. Rather, my focus is on why everyday people turn to crowdfunding and what they find when they do.

Trevor, a single father from Arkansas, reflects some of the ambivalent feelings and lesser-told stories of crowdfunding. We were texting one night while I was rushing to make dinner for my daughter, when Trevor revealed that he worried I might not want to interview him because of how badly his campaign had gone. “I certainly have data for you, but it isn’t a pretty picture,” he told me. Indeed, Trevor’s campaign was a wrenching archive of bad breaks and financial woes. He had type 1 diabetes and was recovering from a severe accident while navigating a flat-lined labor market and single parenthood. He worried about whether he could provide Christmas for his son and about having to choose between buying insulin and keeping their house from foreclosure.

Trevor’s page seemed bracingly honest to me, but his campaign had been unsuccessful by almost any measure. He found himself among that large but unseen group of crowdfunders whose campaigns had never gotten donations. He hadn’t even, he later confided, gotten any page views beyond my own voyeuristic visits.

As we texted, Trevor seemed to waver between blaming himself and shrugging off his campaign’s lack of success: “It’s nobody’s fault, and certainly not yours….Life is a grinding stone, it either grinds you down, or polishes you up depending on what kind of metal you’re made of. Those of us who fight to survive will always cast a wide net. That or I’m a failure as an individual and I have to beg strangers for extra money while I work 40+ hours a week as a full-time single dad. That’s the struggle in my head anyways. Regardless no one has donated a red cent lol so it doesn’t cut too deeply.”

Trevor used the metaphor of a “grinding stone” to invoke the dominant American myth of meritocracy. But his experience speaks to the precarity and stress of crowdfunding, how it leaves some people’s prospects more polished while many others’ turn to dust. Much like the broader myth of meritocracy, crowdfunding seems like something where hard work and deservingness will beget success, but this is rarely the case. For whom, exactly, is crowdfunding an opportunity, and for whom is it a dismantling?

When we later got a chance to speak over the phone, Trevor repeatedly insisted that his campaign had been “just another line that could be cast into the water”—yet another way of trying to get help. Trevor lived in a state where it was hard to get Medicaid, and he admitted to feeling great shame about using those benefits when he qualified for them. For him, GoFundMe appealed to his sense of independence and his skills as a part-time web developer. But as Trevor looked deeper into the GoFundMe economy, he felt less and less deserving of help:

I understand the dynamic to run a successful GoFundMe…to just get it out on Facebook, make It a huge social media scene…and I did research to look at other people’s GoFundMe pages and I was just like, holy shit. I have no right to be asking for money on this page with some of the [other] stories that I read and what they’re going through. So, my fucking story of just being a poor single dad with just bills he can’t afford, you know medical bills, that’s…a lot for me to ask. I certainly couldn’t go on Facebook and make it some big social media thing where I’m begging for money to pay for insulin. I mean, my pride’s worth more than that to me.

Trevor revealed that he posted his campaign online but never told anyone about it. He hoped someone would just come across it and decide to donate. Trevor was an astute observer of the moral hierarchies of the crowdfunding system, internalizing that he was not as deserving as others—so much so that he felt asking for help was shameful, an affront to his “pride.”

How many campaigns are like Trevor’s—created but not shared? It’s hard to say without access to industry data, but industry experts have told me that this phenomenon is more common than we might think. It’s also hard to say whether Trevor gave an accurate account of his campaigning. Maybe he had shared his campaign with his social network, gotten no donations, and his aforementioned “pride” prompted him to tell me a different story.

It is clear that for many crowdfunders, asking for help online is not, as one crowfunder I interviewed, Emily, put it, “amazing.” It is an experience filled with discomfort, shame, and loss of pride. In fact, Emily felt some of that herself when she first started her campaign. “I was really down and depressed, because I felt like I was asking for charity,” she reflected. “I felt like I didn’t really deserve [donations] because I’m not doing anything.” Emily and Trevor’s experiences raise questions about how crowdfunding is affected by social taboos about asking for help and how it reinforces long-standing ideas about who is and is not deserving of assistance.

When people turn to the crowd for charity, they often do it with very low expectations and concerns about how they will be perceived; when Emily experienced that “people actually do care,” it was with a sense of pleasant surprise. But is $1,000 of support for two years of cancer care really “amazing”? And does it distract us from more systematic ways we could care for people and think in terms of what everyone deserves regardless of how they are perceived by the crowd? As I will argue throughout this book, crowdfunding powerfully lowers the expectations of vulnerable people as to what they deserve while enabling those in positions of privilege to assume they are more deserving of assistance because their campaigns are often more successful.

Crowdfunding is appealing precisely because there are so few other options for affording care when crisis hits.

These dynamics are typically invisible to donors, broader publics, and even, at times, crowdfunders themselves. They arise from implicit moral values that crowdfunding feeds on and reinforces. I call these “moral toxicities”—harmful ideas, rooted in widely shared social values, about whether and under what conditions, people deserve help, healthcare, and social protection.

I call these moral toxicities, because, like toxins, they suffuse our environments and can harm our health in numerous ways. Like environmental toxins, these harms are much more likely to accumulate in, and impact, already vulnerable and marginalized populations. Because of crowdfunding’s tremendous visibility, and because it asks users to engage in complex moral questions about whose needs should be supported, it becomes a powerful amplifier and normalizer of certain moral toxicities.

In Crowded Out, I explore how crowdfunding spreads and reinforces several key moral toxicities and examine the broader impacts this has for how we think about health and social care in our contemporary world. The first of these toxicities is free market ethics—the widespread idea that unfettered, competitive marketplaces should extend to things like healthcare systems or, in the case of crowdfunding, deciding who gets financial help for life-threatening conditions. The second moral toxicity is selective deservingness—the idea that not everyone is equally deserving of help, assistance, or access to healthcare. It is fueled by long histories of social policies in the United States that punish, surveil, and dehumanize poor people, immigrants, people of color, and those most in need of assistance. The third toxicity combines rugged individualism with false meritocracy—promoting the idea that every person is solely responsible for their own fates rather than the social or economic inequalities that broadly shape our life chances in the United States.

Finally, there is the toxic belief in downstream solutions: the idea that clever, often technological fixes can be used to patch over gaping, systemic problems in our social safety nets. Of course, crowdfunding can also amplify powerfully beneficial moral norms as well—such as mutual solidarity, communal caregiving, and collective transformation.

We can see how moral toxicities shaped Trevor’s crowdfunding experience. He felt uniquely responsible for his survival and less deserving than others, so much so that he hesitated to share his story or even use Medicaid when he had it. He blamed himself for his failure to succeed in either the crowdfunding marketplace or the broader US economy. And as he kept his page up for more than a year, he hoped, even still, that crowdfunding might provide a fix for the complex problems he faced.

Trevor is hardly alone in these perspectives—these values are so common that it sometimes feels like they are in the air we breathe. They are particularly central to American political and social discourses. But Trevor’s story shows how crowdfunding can further reinforce the power of these moral toxicities, particularly as he turned to this economy and deemed himself unworthy of its help. Trevor’s experience reminds us that “appealing to the crowd” can be a profoundly isolating, and even damaging, experience.

In the crowdfunding economy, moral toxicities are joined by the financial toxicities that are all too common in market-based health systems. From Emily’s burdensome cancer treatment costs to Trevor’s worries over the cost of his insulin, experiences of illness and injury in the United States are made much harder and more harmful by the costs that accompany them. I would argue that the financial and moral toxicities of our health and political systems create ideal conditions for crowdfunding to become an attractive—and in some cases the only—option for help.

Even people I speak to who are enthusiastic about crowdfunding often say that it is a good option for support given how bad things are. As Akhil, a tech worker from near Seattle told me, “[crowdfunding] is very important because systems created by government…there will always be people who fall through [them]…crowdfunding used to happen in local communities earlier, and now it is more spread out [due to the technology].” Akhil is right that many communities have had systems of mutual support for decades, and even centuries, before the appearance of crowdfunding sites.

But the appeal of these sites now, in this contemporary moment, has to do with the sheer volume of need created by market-based health systems and how technology is being leveraged to bandage over these gaping needs. As Lillian, a woman from New York explained, “mostly, people in America…they have financial problems…paying off medical debts. So, for our society [crowdfunding is] a very good opportunity which has helped a lot of people.”

Lillian and Akhil are not alone in these opinions. A University of Chicago survey estimated that nearly a quarter of all Americans had started or donated to crowdfunding campaigns raising money for medical expenses by 2020. At the same time, 85 percent of respondents to the survey said the government should have a great deal, a lot, or some responsibility “for providing help when medical care is unaffordable.” Crowdfunding is appealing precisely because there are so few other options for affording care when crisis hits.

Lisa, a nurse from Tennessee, said she completely understood why people would crowdfund when medical care is so unaffordable:

[I’ll] be caring for patients, for, you know, a couple months, and then their insurance isn’t willing to cover [them] anymore, and so either I have to discharge them or they can appeal it and choose to stay if they’re paying out of pocket, but obviously it’s not like people have thousands and thousands of dollars like on the side ready at will to just drop to pay for whatever they need.

Camilla, from Kentucky, agreed:

My family is not from America, so I’m first generation here. And I personally think it’s insane that [parents of a] type one diabetic…would have to be worried about affording insulin and even have to do GoFundMe [to get it]….I haven’t seen GoFundMes for, like, plastic surgery, because you hate that your nose is not perfect. You know, the things that I’ve seen medical expenses for…on GoFundMe are necessities.

Even casual observers of crowdfunding can recognize that the financial toxicities of the American healthcare system make it a necessary option for many people. In 2022, more than half of Americans couldn’t cover the cost of a $1,000 emergency expense. In half of the states in the US, the median out-of-pocket spending on medical care among people who had employer-provided health insurance was more than $1,000 each year. While costs of hospitalization can vary significantly, researchers found that by 2013, the average out-of-pocket cost of hospitalization for adults with insurance was more than $1,000. Left with few other choices for paying hefty medical bills, crowdfunding is often embraced as a last resort. There, but for the grace of GoFundMe, go we all.

Rather than equalizing access to healthcare, however, crowdfunding exacerbates inequities by reinforcing these toxicities; it provides the most help to those who already have more, not less, access to income, education, health benefits, media literacy, social capital, and other kinds of privilege. Troublingly, in states where medical debt and insurance is highest, medical crowdfunding campaigns tend to earn the least. As a result, crowdfunding is an inescapable cultural phenomenon that reinforces both the financial and moral toxicities of marketized health systems.

In doing so, it is reshaping how we value, access, and practice healthcare and public health. Understanding crowdfunding’s role in our health system—and understanding how it is changing that system—is crucial for anyone who cares about health equity, the future of health technologies, and building fairer health systems for all.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Crowded Out: The True Costs of Crowdfunding Healthcare by Nora Kenworthy. Reprinted with permission from The MIT Press. Copyright © 2024.

Nora Kenworthy

Nora Kenworthy is Associate Professor at the University of Washington Bothell. She is the author and editor of several books, and her writing has appeared in the American Journal of Public Health, Social Science and Medicine, PLOS One, Scientific American, the Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times.