What the NFT Phenomenon Tells Us About the Monetary and Creative Value of Art

Zachary Small Explores the Intersection of New Technologies, Financial Speculation and Artistic Creation

Among the abandoned SoHo storefronts in Manhattan, a gallery lit by candles and computer screens illuminated the cobblestone streets, where a lineup of newly minted millionaires anxiously waded through the winter winds to see what their crypto fortunes could buy. The doors opened on December 9, 2021, to a cavernous space in which dozens of guests sipped champagne and devoured morsels of designer sushi as jazz musicians played. There were venture capitalists and supermodels; basketball stars and their sycophants; film scions and political lobbyists; technophobes and technocrats; technobabes and technorats.

That evening inside Bright Moments Gallery epitomized the new gods and their rituals. They spoke in strange and unfamiliar tongues. Hieroglyphs on the bathroom walls included new terms like “metaverse” and “Ethereum.” Above the toilet was philosophy: “NFTs are the bridge from conceptual art to contractual art.” The messages continued deeper into the gallery, where someone had wallpapered the elevator with hacker mantras like “You can’t spell culture without cult” and “Fear kills growth.”

Tokenization had already exposed the fragility of the traditional system that defined artistic value.Beyond that elevator was a dark cement basement where Tyler Hobbs stood, flanked by two gallery associates: one holding an iPad and the other looking for security threats in the shadows. Clients would join the artist and enter their online wallet information into the tablet, securing the NFTs that Hobbs had coded into existence over the preceding weeks. This precious art cargo had, with the tap of a screen, turned Hobbs into one of the wealthiest artists you’ve never heard of.

The absurd scene inside Bright Moments Gallery made Hobbs look like a fake. He was a lanky thirty-four-year-old former software engineer from Texas, sitting in an empty cellar below a gallery full of partying supplicants and blank walls. And despite a lack of inventory, attendees upstairs had paid $7 million altogether for ninety-nine original artworks. Rembrandt he was not; Hobbs used code instead of a paintbrush. But he never cared about re-creating the past glories of art history; the romantic vision of a starving artist never held much appeal. Before cryptomania, Hobbs rarely earned money from his artworks. It was nothing more than a passion project. “Digital art was usually a sentence of poverty,” he later explained to me. Nowadays, it’s his bank account.

The first windfall came seven months earlier, when Hobbs started turning his creations into NFTs. He understood that tokens were traded on the blockchain, a decentralized ledger system recording ownership information to prevent thefts and forgeries. The blockchain could also classify NFTs as unique assets, deriving their price based on rarity and demand. Hobbs learned these dynamics the easy way in June 2021, selling 999 NFTs almost immediately after offering them online and earning nearly $400,000 worth of Ethereum cryptocurrency in the process. He claimed that secondary sales, which typically come with artist royalty fees of between 5 and 10 percent in the NFT world, had brought an additional $9 million into his pocket.

Hobbs was just one of dozens—if not hundreds—of amateur artists who suddenly found themselves swimming in crypto cash and struggling to understand their own success as more than a combination of hard-earned recognition and dumb luck. He wanted to believe that society’s equation for determining cultural value and the price of art had changed during the pandemic, as people became more accustomed to living online. He wanted to believe that his sudden windfall was a reward for the years he had spent struggling as a starving artist. In other words, he wanted to believe in the fundamental lie that we all believe: merit equals money.

NFTs united the most conspiratorial corners of the internet: the power brokers and the power hungry, who believed that technology could change the world, one pixel at a time. In their rearview mirror: two financial crises and a raging pandemic that had already killed more than six million people worldwide. Up ahead: the capitalist fantasia of a multibillion-dollar industry summoned by artists and algorithms.

Hobbs found himself working in the zeitgeist of economic and technological forces. The same financial institutions and wealthy investors who had capitalized on the pandemic recession and the 2008 financial crisis were looking at NFTs as a technology that could perpetuate the rampant volatility and speculation that had contributed to their record profits. Selling securities as art was a guise for laundering those dynamics often found in the unregulated art market. These forces succeeded by asking questions that none of us, including government watchdogs, could answer: What is the value of art? And how do you put a price on something that is traditionally seen as priceless?

*

If tulipmania provided an outlet for the social anxieties that succeeded a devastating plague, then the NFT boom fulfilled a similar function during the Covid-19 pandemic. Lockdowns produced a strange alchemy in which virtual life became reality, and a speculative financial boom entangled the economic, political, social, and medical emergencies of the time. The framework that structured civilization nearly collapsed, and we lived between the creaking gears of recovery.

Most people were happy to see the old guard in place during this era of uncertainty. President Joseph R. Biden Jr., was the oldest person to ever win the White House, and Congress was controlled by two politicians who were older than him: House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell. The top-grossing film in movie theaters starred a sixty-year-old intellectual property named Spider-Man, and the most successful song on the radio had first been released by the singer Kate Bush in the 1980s. Even the economic challenges were old, combining the stagflation crisis of the 1970s with the poor debt-to-GDP ratios of the 1940s alongside the overvalued tech companies of 2000 and the sovereign debt problems of 2009.

Life might have continued spinning around the circumference of these historical reference points if uncertainty was not such an effective crucible for change; if the young did not inevitably rise to challenge the old.

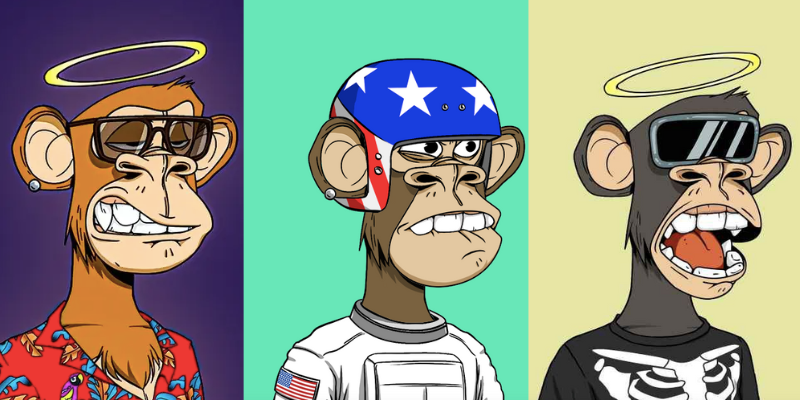

So many questions were left unanswered within their vortex of dada that I experienced inside Bright Moments Gallery and elsewhere throughout my journey of writing this book. The prattling of otherwise intelligent businessmen undermined an extensive reporting effort to outline the NFT industry seriously at the critical moment of its ascension. It made no sense. Grown men were infantilizing themselves in the public eye, claiming that cartoon images of pothead monkeys and pixelated alien dudes would spark a new economic age of digital ownership. The claims were so immediately ridiculous that many government regulators dismissed the industry as a short-lived fad that would perish the way Beanie Babies had. And yet! Their increasingly deranged pitch had attracted nearly $30 billion in venture capital within a period of two years. Younger generations also embraced NFTs as a symbol of their own rising power in society and a definitive breaking point with older models of cultural production.

The contradictions were obvious, so my journey of discovery began with a few simple questions: Why were investors willing to debase themselves for digital collectibles? How did the economic conditions of the pandemic fuel a speculative market cycle? Who benefited from a digital culture war? And what role would artists play in determining the future of the internet?

As a reporter with The New York Times, I had already chronicled the market’s development and realized that an even greater story was hidden beneath the headlines. But I also knew that finding the truth would require an extensive investigation unlike anything that would fit neatly into the newspaper’s column inches. So from hundreds of interviews with artists, gallerists, investors, entrepreneurs, academics, fanatics, skeptics, regulators, watchdogs, and even a priest emerged this portrait of the virtual world triumphing over the physical realm.

Then everything crashed. During the succeeding summer months, when I wrote the majority of this book’s twelve chapters, the cryptoeconomy shredded through nearly $2 trillion, and the once-booming market for nonfungible tokens deflated by nearly 97 percent of its record volume. Suddenly there were NFT collectors being charged with insider trading, international manhunts for crypto developers, and thousands of digital heists. I felt like I was back to where my career had begun: tracking down money launderers and fraudsters in the art market.

My purpose recalibrated with the changing fortunes of my subjects, and a growing consensus that the tech sector was headed toward another recession. A vision of a more ambitious story emerged, one that would tell uncomfortable truths about how the wealthy enlisted the starving artists as bannermen in their battle to re-create the pre-2008 financial system, building an army of crypto Rembrandts battling for relevance and survival. Over the last forty years, the contemporary art market has served as an economic laboratory for the rich to develop a shadow banking system of alternative assets and hedged liquidity. NFTs were a by-product of those experiments, providing financial tools branded as digital art that could be monetized at lightspeed. The implication of this exchange has been wide-reaching. Even after the secondary market for NFTs imploded, the underlying technology has become a normalized part of the art world and the financial system; it has also helped innovate other industries, like gaming, music, advertising, health care, and logistics.

The results of what became a three-year investigation are now yours to read. One might consider it only a slim volume in a much longer history of cultural economics, but the story is nonetheless an enthralling case study for those curious to understand the dynamics of speculation, and how the forces of art, technology, and money once conspired to change the world.

Throughout the book, I have carefully reconstructed scenes and incorporated dialogue drawn from my own interviews and

those sourced from publications, financial statements, internal documents, private recordings, investor slideshows, blockchain data, photographs, and videos. Every detail and conversation appearing in these pages has been subjected to fact-checking, and throughout my reporting I have followed the strict rules of journalism that I learned at The New York Times to ensure my

impartiality and credibility. I have never directly participated in the cryptoeconomy and have no financial interest in the artists mentioned here. The revelations within these pages were also shared with the appropriate people, giving them enough time and information to comment on my findings. Finally, I owe an immense debt of gratitude to the many sources who spent hours and hours speaking with me. These conversations were frequent, spread across several years, and often came during challenging life events. It’s a great privilege to have gained their trust, and an immense honor that they have entrusted me to tell this story.

What follows is a largely chronological account of the NFT market’s rise, fall, and reboot. There will be important side quests along the way: a discussion of NFT artworks in light of the historical reception of photography; a look at how World of Warcraft determined the mechanics of the cryptoeconomy; a war between the billionaire Kenneth Griffin and the crypto investors attempting to buy a copy of the United States Constitution; the time a Miami businessman set fire to a priceless Frida Kahlo drawing that he wanted to sell as a digital collectible; the role NFTs played in the fraud perpetrated by Sam Bankman-Fried and his company, FTX; and how cryptocurrencies normalized incredibly risky bets in the financial sector during the March 2023 banking crisis.

The story includes a baroque cast of characters whose entrances and exits sometimes feel like they are pulled from a nineteenth-century Russian novel. I have done my best to stage-manage their appearances without straying from the truth. But a certain amount of whiplash should be expected; these are eccentric people skilled at using misinformation and needlessly confusing jargon to convince the public of their superiority. Many use pseudonyms to evade scrutiny—yes, there’s a Vincent Van Dough and a Cozomo de’ Medici. Artists have remained at the center of this story despite the noise, and there are four major artists who can tell the tale of NFTs better than anyone else: Tyler Hobbs, Mike Winkelmann, Justin Aversano, and Erick Calderon.

Each man represented a different kind of starving artist who entered the NFT bubble imagining that his career would be one thing and exited the crash realizing that it had become something entirely different. Their desires were simple at the beginning. One hungered for recognition; another craved wealth. But tokenization had already exposed the fragility of the traditional system that defined artistic value, leaving artists to strike hard bargains with greater economic forces in the technology and finance industries. The requisite struggle to bind art and money together into a single concept—the NFT—provoked the most primal feelings of greed, vanity, doubt, and revenge.

*

Those feelings were palpable inside Bright Moments Gallery as Hobbs took the stage. With every push of a button, he generated another artwork from his algorithm. The jazz band stopped playing, and the crypto hordes quietly sipped their champagne as he grabbed the microphone. He reviewed the newly minted NFTs as they appeared, laughing at the variable quality of the results but always providing his best sales pitch: This one looks great. Now, this is truly something avant-garde. Look at the curves on that one. The code attempts to balance unpredictability and quality, using a series of probability equations to determine the likelihood of characteristics like color, scale, and squiggle. The resulting psychedelic swirl of rectangles that Hobbs calls “flow fields” typically resemble the modernist block paintings of an artist like Piet Mondrian, only if someone dropping acid took a wet squeegee to his 1943 painting Broadway Boogie Woogie.

The new art slowly consumed the blank gallery walls as Hobbs kept pace, minting the NFTs, which were instantaneously assigned to collectors via the smart contracts that they had signed in the basement. The old-school artists who bore witness to the experiment were gobsmacked. “This is the art of our time,” said Tom Sachs, an artist who spearheaded his own financialized art movement almost thirty years ago by incorporating luxury brands like Hermès into sculptures of McDonald’s value meals. “This is the new avant-garde.”

Nobody within this audience of the crypto nouveau riche remembered what had occupied the empty storefront before the Bright Moments Gallery had taken over. Maybe it had once been a traditional gallery? Or maybe it was a Prada store? A furniture store? No, a grocery store? None of that really mattered anymore. The crypto hordes had found their own Rembrandt, and the digital art renaissance was beginning—not with a bang, but with a computerized beep.

__________________________________

From Token Supremacy: The Art of Finance, the Finance of Art, and the Great Crypto Crash of 2022 by Zachary Small. Copyright © 2024. Available from Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.