What the Eruption of Mt. St. Helens Can Teach Us About Real-Time Disasters

Ruby McConnell on Catastrophe’s Hard-Earned Lessons

For months in the spring of 1980, the American people watched with fascination the slow progression of a potentially violent natural phenomenon over which they had no control. A bulge had formed on the flank of Mt. St. Helens, an active volcano just outside Seattle, Washington, and it was growing fast, stretching the mountain to what looked like capacity. After a series of steam bursts, scientists from the USGS rang the alarm; a large-scale eruption of some kind was clearly imminent. From there though, the details of just exactly what might happen and when, became murky.

Cascade composite volcanoes, unlike their shield-volcano counterparts on Hawaii or Iceland, are changelings, prone to a wide range of behavior including sustained explosive eruptions capable of generating super-heated pyroclastic mudflows. They are common throughout the world, especially at active plate margins, and their potential for devastation is well-documented; Mt. Vesuvius was one of these kinds of volcanoes. Even so, in 1980, some 2000 years after Vesuvius destroyed Pompeii, little was known about the complex systems that generated such eruptions and even the underlying theory, plate tectonics, was only 15 years old at the time. The volcanologists tasked with monitoring the mountain and predicting its behavior were learning as they went.

You didn’t have to be an expert to know the volcano represented a public safety hazard. The bulge was proof enough of that. The problem was logistics. Mt. St. Helens was the site of major industrial logging operations, a beloved and bustling area for outdoor recreation, and home to many rural residents. And Seattle was a major hub for airline travel and shipping and a commercial center for the region, an eruption could interfere with transportation, ground planes, and make roads impassable.

Officials took action, establishing an evacuation zone around what they determined to be the area most in peril. At first, people complied. But the days dragged on and no eruption appeared; people grew restless. Locals protested the evacuation from their homes and fishing grounds, volcano tourists gathered, businesses pushed to resume operations, people became used to the sight of the bulge. Geologists stuck to their guns and officials backed them; they held the evacuation line.

Then, on the morning of May 18th, they watched as the mountain crumbled. The bulge rumpled and fell, propelled by a lateral blast moving in excess of 300 miles an hour, of ash, pumice, and gases which collapsed into pyroclastic flows that channeled down riverbeds melting the underlying glaciers and snowpack as they went. Fish jumped from the boiling rivers to the banks. It took less than 40 seconds for the entire north flank of the volcano to fail, taking with it the top 1,300 feet of the mountain. Two hundred and thirty-two square miles of prime timber land was felled. The resulting vertical plume, degassed like a well-shaken pop can, erupted continuously for more than eight hours, raining burning ash, pumice, and chunks of ice on the entire state and spreading measurable amounts of ash all the way to the east coast. In Seattle, planes were grounded and flights diverted. Traffic stopped. Streetlights turned on at noon.

It went on for hours, killing dozens of people and sending a plume of super-heated ash into the air that eventually circled the globe.

Last year, on the 40th anniversary of the eruption, we should have been treated to a revisitation of these events. Everyone loves volcanoes. We would have happily taken in a week or more of eruption spectacle—televised specials depicting in grainy newsreels and vivid digitization the rumpling landslide and lateral blast, the grey-black plume churning and rising eight miles into the air, reporters running for their lives from volcanic debris flows, miles of trees knocked over like match sticks, and everywhere, the post-apocalyptic scene of civilization shrouded in ash, kids throughout the Pacific Northwest playing in it, adults shoveling it from rooves, their faces covered by makeshift masks.

It is the nature of things to sustain, to re-establish equilibrium.

But we missed it. Because by May 18, 2020, the entire world was engulfed in another catastrophe circling the globe, one that transformed the landscape of our lives in much the same way that the eruption transformed the landscape of the Pacific Northwest. After months of waiting, the COVID surge had come, leaving us devastated, our cities and schools and churches and neighborhoods emptied of all signs of life, our faces covered in masks. Faced with such catastrophe, how could we have turned our minds to another?

Maybe we should have.

Now, a generation later, those of us that were kids in the spring of 1980 are being faced with many of the decisions, uncertainties, and fears our parents and grandparents were facing as they watched the bulge grow. What are we to do? What will happen next? How will we recover from this? For us, these questions come not as a bulge on the flank of a distant mountain, but as a stream of braided traumas: as pandemic, wildfires, ice storms, and rising sea levels. And they come, increasingly, from within humanity in the form of systemic injustices, mass shootings, and violent militants in the halls of democracy.

If we had revisited the unfolding of those events, it may have informed our handling and framing of where we found ourselves in 2020. It may have taught us something about our collective ability to innovate, collaborate, and adapt to real-time disasters, or implement public safety endeavors like mass vaccinations, or about the reach of our understanding of and control over natural systems, about timescale, risk, uncertainty and error.

So many of the choices and challenges we faced and will face ask us to rely on science, on policymakers, elected officials, and one another making sound decisions, the stakes have been so high. Maybe it would have helped us to learn about old Harry Truman, a prospector and bootlegger, who refused to evacuate his cabin saying, “You couldn’t pull me out with a mule team. That mountain’s part of Truman and Truman’s part of that mountain.” and now is buried under Spirit Lake. Maybe we needed to see a mountain fail, entire forests felled in moments, the sun blotted out of a city skyline to be reminded that in geologic time, catastrophe has always come, and it has always brought hard lessons.

One of the people who died that day, Dave Johnston, was lost to such a lesson, a scientific failure of imagination. Dave was a volcanologist working with the USGS to help monitor the volcano. On the morning of the eruption, he was camped at their closest observation point, a low ridge that sat just five miles from the volcano. From there, the bulk of the bulge stared straight out at him. They thought it was safe, but when the flank collapsed, he barely had enough time to yell “Vancouver, Vancouver! This is it!” into his radio before being engulfed in the lateral blast of depressurized lava and gas that followed. The hindsight was immediate. Previous to that day, in all of our human experience, volcanoes had erupted up, out of a central vent not laterally and without any previous experience, they had simply neglected to foresee it as a possibility. Today, we know that such behavior is not uncommon. The deposits from similar eruption have been recognized at similar volcanoes around the world.

When the eruption stopped there was nothing left. By all accounts the volcano had completely obliterated the blast zone. Nothing survived. What hadn’t been incinerated was sitting tens of feet under still-cooling deposits. Even the river was gone; buried. It would take hundreds of years for life to return, everyone said, if ever.

But it did. Rains came and the sun shone and birds flew overhead and chipmunks burrowed and the river dug its way out from the ashes and so did everyone else. Over time, the lessons learned on the mountain made their mark. Mt. St. Helens instigated the modern era of real-time volcano hazard evaluation, monitoring, and communication.

Today, the Cascade volcanoes and active volcanoes around the world are monitored by a network of scientists, as are other natural hazards such as earthquakes and storms, allowing policymakers and the public to make informed decisions about how we choose to live alongside them. By the spring of 2020, the land was in recovery. Trees were growing, the river had surfaced and was cutting a new path through the deposits, wildflowers were in bloom, and, yes, the mountain was still steaming, though COVID protocols meant few humans were there to witness it.

Call it endurance, call it resilience or faith or perseverance, but understand that the lesson from the volcano is this: it is the nature of things to sustain, to re-establish equilibrium. Humanity does not stand alone in the face of forces larger than ourselves. We are part and parcel of these systems and in that there is solace and hope.

__________________________________

Ground Truth: A Geological Survey of a Life is available from Overcup Press. Copyright © 2021 by Ruby McConnell.

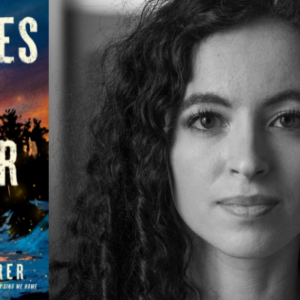

Ruby McConnell

Ruby McConnell is a registered geologist and outdoor adventurer who writes about nature, art, and culture with a particular emphasis on the intersection of the environment and human experience. A recipient of numerous honors, including the Oregon Literary Arts Fellowship, she has written extensively about the Pacific Northwest and the environment in scientific and literary journals. McConnell is the author of A Girl’s Guide to the Wild, A Woman’s Guide to the Wild, and The Nature Journal and Activity Book. She lives in Oregon with her husband, Paul.