What The Endless Summer Gets Right—and Wrong—About African Surf Culture

Kunyalala Ndlovu Considers New Possibilities For Framing Global Surf Culture

I saw Teju Cole in a packed auditorium at the Directors Guild Theatre in Manhattan, in late October 2019. He had taken part in an evening conversation with fellow author Zadie Smith, talking through a number of ideas of public interest. The one that struck and stuck with me: you have the right to reimagine your own world through another individual’s narrative—in particular a photograph.

On reflection, I consider surfing to be one of the most visual cultures, which is probably the only reason you, dear reader, are here. Surfing is one of the few recreational activities where a number of its devotees decided to take part in the culture in part after experiencing a film or seeing a photograph. These framings of light are the gateway drug to the greater experience, and have always been portrayed in such a manner that desire sits at its core.

But perhaps there is more. Allow me to peel back the wax backing to make this stick. Observe this photograph I’m looking at from Teju Cole (above), simply named “Brazzaville, 2013.” A young black boy not much older than 12 sits on the outside of a river, but on the inside of a wall holding a red pole in the middle, with the cold water churning behind him. In the top right corner, we can see in soft focus some other boys playing in the water in the distance. He looks poised, not too dissimilar to a grom in the lineup waiting for his moment of action—only he knows the precise moment.

When you view this image before you, all at once you’re compelled to fill in the gaps of what is unknown, including the obvious—no surfboard or surfer in sight. Yet all it made me think about was the experience of surfing in Africa. Is he playing, or is he waiting? With who, or for who? Where is this spot? Most important, how close is he to the ocean?

The African continent, depending on who you speak to, holds a duality: of being both the first and the last place one might consider for good surfing, let alone a different type of surf culture. Surfing on the whole has remained essentially a Western trope that seemed to only bed down in South Africa, a land that notoriously kept anyone who wasn’t fair-skinned off all the good beaches for many years. Waves were still found elsewhere, but were not as well documented, and this perception has been driven by an overly saturated bank of surfing photography and film that drives surf culture through a Western gaze. So far so good.

Then came our first visual cloudbreak moment in surfing image culture—the glorious 1966 16mm masterpiece, The Endless Summer, shot on the holy grail of celluloid cameras, a Bolex H16. This was an object I personally desired, after discovering the surf films of Thomas Campbell. This clockwork beast is robust, light enough for one person to operate, and—like every good surfer has to use their arms to paddle into a wave—it is entirely hand wound. In a world of cumbersome equipment, this was an A-bomb going off—so much so that a young David Attenborough, elsewhere on the African continent, simultaneously reframed how the world experienced wild animals—with no one’s permission, just an inappropriate curiosity. Remarkably, the first stop of the film shows our expected white male voyagers Michael Hynson and Robert August arrive at bustling Labadi beach, in Ghana.

For the record, and my peers, I’ll state that this scene stuck in my mind, over the ever-clichéd Cape St. Francis scene. Notice the two outsiders arriving with their logs and no wax—famously using hair wax, which melted off instantly in that blistering sun. Fully confident in the waves before them, they start a session in front of a number of young boys and men on the beach, who had apparently never experienced surfing before. But when one pauses the moment the two outsiders walk down toward the water, you can see in the background, in soft focus, little boys playing with what appear to be flat pieces of wood in the water. They were in fact surfing; they just didn’t have that name for it yet. But who gets to decide that, anyway?

The remaining onlookers could have their moments of observation posited as their own form of inappropriate curiosity. Freeze-frame on a young black boy, not much older than 12, holding on to some rope, looking into the distance with a big smile, and the hot West African waters churning behind him. His name was Samuel Assam Adjeijo and he was one of the Head Coil Ropers—young fishermen who form massive teams to cast their spiderweb of nets out into the ocean.

It is at once all about African surfing, and at once nothing to do with surfing in the typical sense.

The most compelling part of that composition is this: Samuel Assam and his friends, by accident, became some of the first visual framers of African surf in popular culture. All things considered, and when one can look past the pinch of racist commentary in this film, it pulls forward a clear picture of outsiders bringing in a new interest that locals should theoretically fall in love with. It is at once all about African surfing, and at once nothing to do with surfing in the typical sense.

If one can reimagine aspects of African visual culture on the periphery of surfing, we open up a myriad of avenues for driving a new culture for the continent as well. Samuel assumes the role of the foil character—the character who exists to highlight the qualities of the protagonist. The picture was a picture of African surf, with the presence of wooden boards off camera, hair wax floating in the ocean, perfect waves breaking to become the story within the story.

I’ve only ever had the privilege of meeting Royden Bryson once; through a friend of a friend, he kindly took us out for a surfing lesson while we students had the worst hangovers. Royden is no stranger to the churn or to the foam of a river. If you look closely at the photo above, you can see him tucked neatly like a hairpin into a brownish green barrel in the Zambezi River. This photo, taken by legendary African surf photographer Greg Ewing, was composed between two river banks, between two borders of two landlocked countries: Zimbabwe and Zambia. It is the most compelling African surf photo I’ve ever experienced, amplified further by the fact that it is nowhere near an ocean. It is once again the correct positioning of African surfing—the story within the story within the story.

As legendary Magnum photographer Alex Webb once poignantly remarked, here are moments where instead of us trying to take the photo, we must realize that it is the photo that takes us. If we surrender to this shift, maybe we will begin to see a reframing of authentic African surf culture as diverse as the continent it inhabits. Every good photographer knows that as we train our eyes and minds to see new things, even the light must suffer, as it touches parts of our minds that have never experienced it before. This is our starting point. As The Endless Summer crew remarked of their attempts to frame a global surf culture, “We were determined, mainly because no one told us we couldn’t.”

And so say all of us.

Yes, on the continent we’ll have to work harder in driving new ideas, images, and culture, but this is not a disadvantage; rather, it’s a golden opportunity. While the Western surfing-photography oeuvre is awash with more of the same, African surf culture has a slab of what everybody else does not—we just have to let it show us. Hawaii may be too far, but have you tried surfing the Zambezi River? How many more rivers on the continent might work one week out of every year? Remember that long wave in Angola that’s barely been touched? Also, what’s going on in Somalia? From Google Earth it looks like point break country, all facing south—is it completely flat all the time? The possibilities are endless for us to reimagine a new future of surfing culture.

Readiness is all.

__________________________________

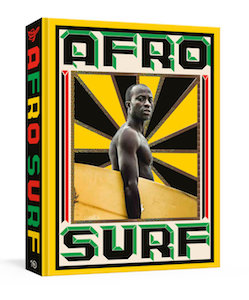

Excerpted from AFROSURF. Used with the permission of the publisher, Ten Speed Press, a division of Crown Publishing Group. Copyright © 2021 by Kunyalala Ndlovu.

Kunyalala Ndlovu

Kunyalala Ndlovu is a creative polymath whose expansive practice delves into the realms of film, art and writing. His focus encompasses experimental film-making, slice-of-life writing and working with brands, businesses and institutions to help them authentically connect to culture.