What the Dead Leave Behind: On the Way a Life Can Inhabit a House

Emily Austin Navigates the Grief That Lurks Within the Best of Memories

I spent a lot of time at my grandparent’s house as a kid. Both have now died, but the house still stands. It exists in my hometown on a ravine lot that backs onto a gully. They bought the house in the 1970s for five dollars, or however much houses cost then. Strangers live there now.

When I think of my grandparents, I picture my grandma asleep in the front room of that house, with a book open on her chest, and my grandpa, also asleep, in the back room with America’s Most Wanted blaring. It is bizarre to think of that house existing without them snoring in it. It is even more strange to think of it with new people inside, who I do not know, and who did not know my grandparents.

I used to bike to the house as a kid and pretend I did not know how to operate a VCR so my grandpa would put in a movie and watch it with me. I would draw on all their printer paper. My grandma would collect the sheets after I left and bind little books of my terrible scribblings. My grandpa was hesitant to ever move out of the house because it was near my high school and sometimes my siblings and I would visit over lunch. The backyard faced a gully that had tree roots that wove in and out of the dirt, and a ravine my siblings and I would play beside while my grandpa watched, hands on his hips, telling us not to go too far. Whenever I was sick at school my grandpa was who would pick me up, and he would take me to that house, where I would lay on the couch, and recover by watching true crime documentaries with him and my grandma.

After they both died, I felt bad when I went by that house. It was not just that I felt sad, something about the strangers inside it bothered me. The thought of someone else in their living room, where my memories of them are anchored, was somehow an affront.

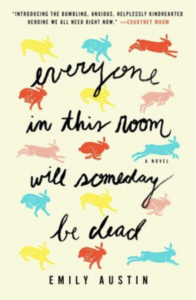

Death is difficult to face. Rather than look at it head on, most of us cope by ignoring that someday we, and everyone we know, will die. Some of us try to do things like have children or write novels that will hopefully exist after we are gone. (I wrote a novel titled Everyone In This Room Will Someday Be Dead, which is, as you might be able to tell, topically related.) Others try to face the truth, despite the depression and grief that comes with doing so.

There is a truth to life that is difficult to access if you are not grieving or depressed.

Depression and grief are sometimes described as dark clouds that hang over us and distort how we see things. When you are a depressed, grief-stricken person, however, it does not feel like your perspective has been distorted. It feels like you see things more clearly than other people do. It is true that we will all die. It is true that the objects we touch and the garbage we create will exist in landfills long after our own bodies decompose. It is true that our family and friends will all die. They will leave behind clothing, half-used shampoo bottles, and used toothbrushes.

When my grandma died, my sisters and I helped my grandpa by cleaning out her closet and toiletries. She put half used bars of soap in drawers to keep their clothes smelling fresh. She wrote funny and wise stories and journals, and there were sheets of paper and torn cardboard with her handwriting on it throughout all of her things. I remember pouring out a half-drunk glass of water beside her bed.

When people die, their homes will likely be sold and lived in by strangers, and it will occur to us left behind how devastating it is for a building to last longer than a person, and how offensive it is for the sanctity of that building to go unperceived by outsiders.

This year I bought a little post-war house in an estate sale. Before me, it was owned by a woman and her family for about sixty years. When I moved in, I found little notes taped inside the kitchen cupboards with phone numbers and recipes, and a calendar behind a shelf from 1992 covered in reminders like “return Blockbuster videos.” The kids, who I assume are in their fifties or sixties now, wrote their names on an unfinished wall in the basement. There are flowers I did not plant sprouting in the garden, and a cup of bleach I inherited by the washing machine with the word “JAVEX” scrawled across it in someone else’s handwriting.

Over the holidays, I intentionally placed a lit Christmas tree by the front window. I did that as a sort of signal, thinking it might be nice for her family to see if they ever drive by. This spring I have been taking care of the garden, weeding the flowerbeds, and referring to the returning perennials as someone else’s flowers.

The novel I wrote is about a morbidly anxious young woman named Gilda who stumbles into a job as a receptionist at a catholic church. There she hides her atheist lesbian identity and becomes obsessed with the previous receptionist’s death. Gilda is fixated on death and is hyperaware of how simultaneously insignificant and important everyone is. Writing her provided me with a healthy way to lean into my own morbid anxiety, and she and my new house helped me arrive at a sort of enlightenment.

I do not feel bad anymore when I envision the strangers in my grandparents house because I know when they chip the wall, they will see a layer of their paint, and that inside the closets might still have wallpaper from when they lived there. There is still a laundry chute in the bathroom upstairs, and the windows still face the same view. I think that even if the house burned to the ground, there would still be some perceivable indication that Jim and Gloria were once there.

It occurs to me frequently that my house was owned by a woman and her family before me. I am very aware that the house was once, and in many ways still is, someone else’s.

There is a truth to life that is difficult to access if you are not grieving or depressed. If you find you have looked behind the curtain and seen that truth, try to walk even further behind the stage. When someone we care about dies, and we are forced to face the awful truth of it, we do things like resent the new people who move into their old homes. We ruminate about how devastating it is for a building to last longer than a person; however, I have learned in my little house, while writing and rummaging further behind that curtain, that is not really true.

__________________________________

Everyone in This Room Will Someday Be Dead by Emily Austin is available via Atria Books.

Emily Austin

Emily R. Austin was born in Ontario, Canada, and received a writing grant from the Canadian Council for the Arts in 2020. She studied English literature and library science at Western University. She currently lives in Ottawa. Everyone in This Room Will Someday Be Dead is her first novel.