Ma Lou

Ezili, o! M san zo, ey!

Ezili m san zo!

M san zo lan tout kòm!

Ezili, o! M san zo, ey!

M san zo lan tout kòm!

Ezili o! M san zo.

Oh Ezili! Hey, I have no bones!

Ezili I have no bones!

I have no bones in my entire body!

Oh Ezili! Hey, I have no bones!

I have no bones in my entire body!

Oh Ezili! I have no bones.

–Vodou traditional for Grann Ezili

*

Port-au-Prince, November 25, 2014

“Oh. Oh ye, oh ye. Manman’mwen. Oh ye, oh ye, oye. M’pa gen zo ankò!” My old mama used to say these words when she grew too old to draw water from her own well. I remember. When I made my way back to see her in her last days—standing in the tap-tap truck for long hours as we traveled the serpentine road leading out of the capital to the villages of the coast, all the way to Saint Marc, where I was born, and my mother was born, and her mother before her—I was troubled to see her diminished frame in her bed. I could see her bones through the frail, wrinkled skin that lay limply across them. I could see the bones, but still she moaned to the goddess plaintively: “I have no bones; I have no bones.”

Now that I am old like her, I understand the moaning of her last hours. Yes, Mama, you had no bones, and I did not understand you. I did not understand. She complained of cold during the hot days and of heat in the coolness of night. I rubbed a cloth dipped in river water over her flaccid skin, slowly, slowly, in circular motions, to warm her, to cool her. She sighed as I did this, sighed for the temporary relief, without a sense of hope, as a soldier of war would after being shot, waiting in the trenches to be found by enemy or kin, hoping not to be found by an enemy. At night, I lay beside her and put my arms around her, two blankets covering us. She shivered in the night even when it was still hot. She died July 15, the day that the devotees climb the waterfalls in Saut d’Eau, seeking penance from Metrès Dlo, seeking healing and renewal. “No bones,” she said, her eyes wide open, looking through me. “No bones.”

But, in the end, all that remained was skin and bones. When she died, the wick of light in her eyes flickered, then disappeared, a lifetime of misery extinguished, very slowly. Just a heap of bones.

A month ago, the dictator’s son died. I wonder who mourned his lifeless body. What the gods had to say. Whether his passing meant that we would be delivered of whatever curse his father, the god of death, had set upon us. Thinking about it, I realized that he was a man like other men. A heap of bones like my mother.

I thought about going to Saut d’Eau for a long time after Douz, to bury my mother’s bones. I had never been but had always wanted to go. I thought about the stories that my husband, Lou, told me about the place. He went there just before we met, on the feast day in July. He asked the gods to bring him to someone like me. Not someone, he corrected himself, you. A soul mate. You, he said emphatically. Lou was a vodouisant all his days, made altars, offerings, participated in the feast days. I watched him without saying anything. I was a Catholic, and that was that. We never discussed our difference. Had he been here after what happened, happened, he would have danced with the mourners. I would have watched him. Lou’s memories were my own. That’s why it didn’t bother me that once we were married, everyone took to calling me Ma Lou, echoing my constant references to him in my speech (“my Lou,” “my Lou,” I always said, as I still do, as if everything he told me were sacred and true; I wanted to believe that this was so). Everyone still calls me by his name, though Lou is long gone. After what happened, happened, it seemed to me then that it would be best to believe in gods that had not harmed me. Lou’s gods. My mother’s gods. Being sent to Catholic school early on severed me from them, even if I was only to become a market woman. At least I could read, count, and pray the catechism. I thought this made me lucky, but in other ways, it made me poor, like a pocket turned inside out, empty of coins.

My Lou had told me about the mapou cut down when the priest and a parish official stationed at Saut d’Eau were told that Ezili Wèdo, goddess of the waters, had made a shimmering apparition. Saut d’Eau was made up of two waterfalls and it was said that the second belonged to Damballah, the serpent god, giver of all life. The priest had the tree cut down, but the gods remained. That priest later lost both his legs in a freak accident. The police captain who had overseen the cutting down of the tree temporarily lost his mind. His faculties returned when he went into the waterfalls and asked for forgiveness. Now, everyone goes to the falls. Even I went, some two years ago, when I could begin to stand on my own two legs, move forward again, to cleanse the bones.

Before going, I thought a long time about the priest who’d lost his legs. Thought about the boy in the camp whose leg they’d cut off, whose mother had lost her hold on reality. Were they being punished for something? For not believing? But I could not believe in gods that would punish the helpless. No. The earth had buckled and, in that movement, all that was not in its place fell upon the earth’s children, upon the blameless as well as the guilty, without discrimination. It wasn’t the boy who’d lost his leg, who was guilty, it was the rest of us who looked away from people like him, people who could have been us, lame, stumbling, afraid to go out of their houses in the light of day for fear of what could happen next. We’d lost our legs—sea legs, land legs, the ability to stand up for ourselves. I needed to cleanse the bones myself, to put all this behind me, return to the land, to my mother’s land, remember everything, and forget the last two years of death begetting death. But, for some time, before going to the waterfalls, I did not know where to start. How to rise again and set out. I am just an old market woman. A relic.

Yes, yes, me, Ma Lou, I admit, finally, that these bones of mine are old, worn out, fragile like the eggs I take to market that everyone wants, even the Dominicans. I never thought I would see the day that Dominicans would want anything we produced for ourselves. But all they really want is to sell us their good-for-nothing eggs produced in factories. My eggs are warm from being dropped from the hens’ insides. That’s how fresh they are. That fresh.

Fresh like Jonas, who used to count his steps all over the market. Counted how many of everything I had to sell, how much I made with every sale. Counted the eggs I had, to see how many his family might purchase. They were five all together. Not the poorest. Not the richest. Just counting their pennies like all of us, counting and putting them away when there weren’t enough to buy what they wanted. “Don’t worry,” I told him, when he would come to me with his fingers filled with grimy folds of paper, our useless gouds. “Don’t worry,” I’d say. “You save, and one day you’ll have enough to purchase the whole dozen! For you, and for your family, the whole carton just for you.” He would smile when I said that, be less embarrassed if that day he had been sent to purchase two or three eggs, sometimes only one. He came, that day, to get one egg for his mother, but he never reached home.

He’s gone, that boy, along with his sisters, wee things that came to the market only when the mother was there, trailing behind like ducklings, with the same odd waddle of a walk that only winged creatures have. Perhaps this is why they weren’t for this earth for very long. The girls five and two, the boy all of eleven in that New Year. She sent the boy, alone sometimes, to run errands for the family, sometimes let me have him run errands so he could make a little of his own money on the side, a few gouds to call his own, to make him feel grown, or growing. I knew him well, as did my clients for whom I had him run errands, especially up at the hotel on the mountain, perched above the city. He was quick, quick, and mostly reliable. He reminded me of my own son, Richard, at that age, except that I had a presentiment that unlike mine, he would grow up to be a fine man. I had been wrong concerning them both. My son grew to be a wealthy, respected man, though I no longer knew him by then. Jonas would never become the man I could see hovering already in the shadows of his eyes and vanishing smiles.

The girls were crushed beneath a house over there, not far from the market. Playing in the streets. Darting in and out of the houses, nothing unusual. I watched them do this daily from my seat low to the ground. Watched the boy count his steps from his stoop to the market, then to my stall, backward, forward, as if he could solve a mystery with his calculations—so much like his father, the accountant with hardly a cent to his name, but rich in other ways: his family, for one. Anyone could see that he had married the love of his life, ran to her like a man runs to water in a desert. No wonder it would be fire we would have to save her from, in the end, months after the disaster. The boy had left my stall with his one egg for his mother in hand, then gone down the street and into a house with a television on, turned out to face the street so that everyone could gather inside and outside to watch the futbòl games or, that day, a soap opera. The woman who owned the house was a childless woman, a widow or a divorcée. She, too, would not survive.

When the earth moved, the houses fell to the ground within seconds, jolted when the ground stopped swaying and crushed everything that had remained. The girls were not the only ones left crying below: the whole street swayed; the earth rippled like a carpet heaving itself of crumbs and dirt that a distracted housekeeper had forgotten to sweep away. I left my stand and all my wares—the piles of mango, the eggs (they would fall, smash against the ground), the packs of Chiclets, the ripe avocadoes—and made my way toward the voices, not thinking of my own small house up and away in the hills. I was not worried for my own: Anne, my granddaughter, had left for her work, far away in another country, after her mother’s funeral, and Richard, her father, my son, well, we had stopped worrying for him long ago, carrying with us solely the memory of him as the small child we had raised, before he left us, leaving behind, carelessly, a stray seed for us to water. We buried our grief in the process, watching Anne grow. Our son, the man, we did not know.

I watched. That’s what old market women do: we watch. But this time, the lot of us market women sprang to action, even as our bones creaked for lack of cartilage and oil. Like the others on the street, we used anything in hand we could find. Useless things like spoons and forks, the metal ends of umbrellas, as if our puny things, our fingernails, could move all that. Only the lucky were saved. Being lucky meant simply that you were closer to the surface, or that fewer things blocked the way to being found. We heard people on their cell phones, all up and down the street, begging frantically for help, giving directions to where they thought they were beneath the rubble, within the rooms of their houses. Phones rang and we heard people answer them. Then—fewer and fewer voices. The tinny, persistent ringing of cell phone tones: different songs rising like wind from underground with no answer.

We heard our own voices, screaming at each other, asking for help, not knowing what to do. Faces covered with dust, and sweat, and other things later to be determined. What to do? There was nothing to do but to scream, try anything, flail our hands, scratch at the earth like my chickens when they get confused because their fresh-laid eggs disappear, one by one, and still they lay more. Try anything and still, it’s too little. After the earth rose and split open, yes, I saw angels walking, but there had also been dust, white dust, everywhere, caking all objects and every moving thing. The dust came from the concrete crumbling to pieces as buildings flattened, but there were also other things mixed in, blood and bones. Had I mistaken the walking dead for angels, survivors stumbling through the debris with the same white flakes covering their bodies from head to toe that covered mine?

Eventually, we, the market women, remembered our oil lamps and lit them, one by one, those of us who could. Only part of the market had been crushed, the part against a wall. Still, it was impossible to tell what belonged to whom, and at that point, no one cared. We worked at freeing those we could, said prayers for the others, promising deliverance to those we could not get to, to give them some solace, some hope in their final moments, because salvation would soon be theirs. Then back down the street, darting back and forth. Using the goods from the market to feed those working at rescue. Doing what we could, as we always did, our large bodies moving through the rubble as if we were land whales, made for swimming through dust-laden air, made for parting human waves.

We treated everyone alike. They had become all the same, were always the same. Something we had always known from our low-to-the-ground perches, observing life like budgies, our heads wrapped in colorful scarfs to keep the heat of the sun from roasting our brains, sweat slipping down our necks, draping the half-moon of our chests exposed above the breasts. We fanned ourselves, but it didn’t help. Chalè! Heat came with the territory. But not this. Not this. A different kind of heat. Sitting here under the hot sun all day, we ripen.

_________________________________________________________

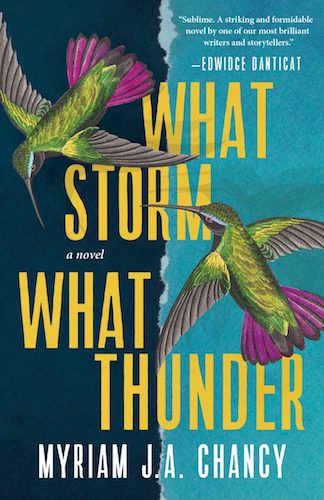

Excerpted from What Storm, What Thunder by Myriam J. A. Chancy. Published with permission from Tin House. Copyright (c) 2021 by Myriam J. A. Chancy.