What Silent Film Taught Me About Storytelling

Dominic Smith on the Power of an Obsolete Art Form

In 2013, the Library of Congress reported that more than 75 percent of all silent films are gone forever. As a writer obsessed with the gaps and silences of history, this statistic grabbed my attention. At the time, I was working on The Last Painting of Sara de Vos, which explores the largely forgotten story of the women painters of the Dutch Golden Age, but the idea of this disappearing medium stayed with me. It seemed less like a gap or silence and more like an entire missing layer of our storytelling history.

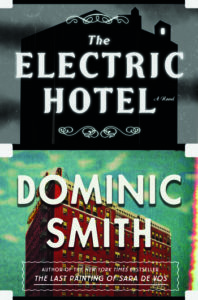

A few years later, when I was looking for a new novel project, I found myself returning to the vanishing world of silent film. Just as I had immersed myself in museums and restoration studios to understand 17th-century Dutch art in my previous novel, I wanted to steep in the medium and atmosphere of silent film. Research for The Electric Hotel, which tells the story of a lost silent masterpiece that ruined the careers and lives of its filmmakers, took me deep into what remains of the early film era.

At the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., I navigated the fluorescent, underground warrens to watch films made before WWI, and I trekked out to the Library’s Packard Campus in Virginia, where they regularly screen old silents to live music and where the most vulnerable celluloid is stored in a former nuclear bunker. It turns out the celluloid nitrate, which is highly flammable and prone to decay, does well underground with controlled temperatures and humidity levels. I picked my way through Fort Lee, New Jersey, looking for signs of the old studios. Fort Lee was not only America’s first movie town, it was also the place that popularized the cliffhanger as a narrative convention—picture damsels in distress and serialized melodramas filmed out on the Palisades. I even made the pilgrimage to Lyon, France, to the childhood home and photographic plate factory of the Lumière brothers, the inventors of cinema. I stood in the spot where the very first film was made.

It’s hard to say exactly what I was looking for in all these encounters. Research for a historical novel can cast you adrift in far-flung locations, not knowing exactly what you came there to see. It can find you laboring in distant reading rooms and libraries, suffering from a kind of archive fever that insists the next box of manuscripts or artifacts will finally reveal the time period to you. I’ve made a rule that if I ever find myself ordering up a lock of Byron’s hair or Churchill’s fountain pen (or their analogs) in some archive, then it’s time to immediately quit the research and begin the writing. Part of my motivation in the silent film research was to understand how and where these films were made, and why they had disappeared in such large numbers, but I was also looking for a moment of bracing contact with the medium itself. I wanted to experience a silent film the way a moviegoer might have experienced it after its initial release a century ago.

So many of the silent films we’ve seen have that jittered, slightly accelerated look, as if everyone walked 20 percent faster before 1927.

In the fall of 2017, I attended the world’s largest silent film festival in Pordenone, Italy. More than a thousand people come to Le Giornate Del Cinema Muto each year—scholars and professors but also librarians and accountants and cinephiles who sit in the dark for a week and watch these old silent ghosts shimmer across the screen. They spoke about silent film directors and actors the way art enthusiasts speak of old masters, with reverence but also with a collector’s glee for trivia—the provenance of previous exhibitions, the anecdotes of lost masterpieces. Hitchcock’s first film is lost, but if it were to show up in an attic or basement somewhere, there’s a good chance it would be shown first in Pordenone.

The Verdi Theatre, where the festival takes place, is an operatic space with swooping balconies, red plush seats and a cavernous orchestra pit. This is where I had my conversion experience, where I finally felt myself swimming in these nitrate shoals. One day, there was buzz at the festival because 23 minutes of an early Louise Brooks film, Now We’re in the Air, had recently been rediscovered and painstakingly restored. It had been found in fragments in a Czech archive, the English inter-title cards missing. As the first restored images dappled across the screen, as the music floated up from the pit, the entire auditorium sat transfixed.

It’s fair to say that Now We’re in the Air was not a rediscovered masterpiece. The plot for this “aviation comedy” involved air balloons and airplanes and a scheme to bilk a fortune from a wealthy family. Louise Brooks, who would become the iconic flapper girl of the 1920s, played twin sisters, Grisette and Griselle.

For me, the rush of seeing this film had nothing to do with the plot or the aerial shots over whirring landscapes. It was, instead, anchored in a feeling of immediacy and veracity. So many of the silent films we’ve seen have that jittered, slightly accelerated look, as if everyone walked 20 percent faster before 1927 (the year sound roared in) than they do now. It turns out that this effect is largely a technical fault, due to hand-cranked cameras and projectors struggling to maintain consistent frame rates. Now We’re in the Air was, more or less, seamless and pristine. And as I watched it, I felt a visceral kind of nostalgia for the audiences of this earlier time. I was seeing a portion of this film as it had been screened 90 years earlier.

When those 23 minutes were over, I felt a kind of deflation and I went back to my hotel room to Google Louise Brooks, only to discover her sad demise. In a 1979 New Yorker profile, the critic Kenneth Tynan described her as “the most seductive, sexual image of Woman ever committed to celluloid.” In the article, Tynan writes about going to see Brooks long after the Klieg lights have dimmed on her career. She is in her seventies and all but forgotten, beset by degenerative osteoarthritis, and living in a tiny two-room apartment in Rochester, New York. Brooks died six years later.

In fact, only the right things need to be dramatized, and the rest can be artfully invoked, inferred or just outright told.

The story of Louise Brooks—the paradox of her vitality on-screen with what awaited her in later life—directly inspired the creation of my filmmaking characters in The Electric Hotel. But, more immediately, after my experience in Pordenone, silent films started to infiltrate my life. I routinely watched two films a day, technically under the guise of “research,” but more truthfully as a way to find my way back to the red plush seat in the Verdi Theatre. There was nothing in my Hulu or Netflix queues that held my attention, but I was delving deep into the early works of Jean Renoir and F.W. Murnau. My dreams filled with the imagistic distortions of German Expressionism and I found myself trying to lip read conversations across a crowded coffee shop. When I went to write a scene in the novel, I kept thinking about inter-title cards, the inserted dialogue of silent films, and I brought that kind of economy and distillation into the evolving pages of the novel. Even the format of the manuscript pages themselves—paragraphs separated by white space, the omission of quotation marks—faintly resembled early photoplays.

Over the course of writing The Electric Hotel, silent films began to teach me how to listen to my characters and their world in a whole new way as a writer. And they reminded me of narrative lessons that I thought I’d already mastered.

For example, I’ve always been interested in narrative economy as a writer, but silent film reminded me how doing more with less is a kindness to the reader or the viewer. When I teach MFA students, I sometimes see the temptation to create too many scenes, as if a complete dramatic breadcrumb trail is essential for the story to have an emotional payoff. In fact, only the right things need to be dramatized, and the rest can be artfully invoked, inferred or just outright told. If a character is experiencing an emotional change or conflict, if the inner life is pushing at the surface, then it might be a good candidate for dramatization. I found myself throwing out one scene after another in my evolving novel. At one point, I took three early chapters and distilled them into one, interwoven sequence.

Silent films also offered a crash course in subtext and gesture. Since early moviegoers didn’t want to slog through endless inter-title dialogue cards, subtext, gesture and being able to read a scene visually were all essential. (During the early film era, many early actors were still emerging from the big gestures and acting styles of the Victorian stage, but it’s also true that naturalism was on the ascent.) If subtext is what lurks below the surface of a scene, in the realm of the unsaid, then body movement and gesture allow the reader or the viewer to feel the pressure of the subterranean. In the midst of binge watching early Jean Renoir, my novel scenes began to layer and deepen with subtext and silence.

In the early days of silent film, the cameras were mounted in one place and they had a fixed focal length. If you wanted to get a closer shot of an actor’s face, you had to move either the actor or the camera. There was, by definition, a sense of stillness in the way scenes were staged. Actors entered and exited from within the same visual plane. As moviegoers, we spent longer in each visually defined space, and therefore we had more time to make connections between the contents of a room or outdoor area and the emotional lives of the characters. This careful use of objects and atmosphere is something I started to think about as I staged the scenes of my novel. Was is possible to stay in each place a little longer, to make the details and objects matter a little more, without sacrificing pace?

When I think back now on these lessons and my days in Pordenone, I feel connected in some real and tangible way to that first audience who assembled in the Paris winter of 1895 to watch two French brothers unveil their cinématographe invention. I can feel their awe, hear them calling out when an omnibus appears to careen directly towards them. I can see them, watching this silver-skinned vision of their own lives on screen, whispering with delight. This, it turns out, is the moment of contact I’d been craving all along.

__________________________________

The Electric Hotel by Dominic Smith is out now via Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Dominic Smith

Dominic Smith is the author of The Last Painting of Sara de Vos, a New York Times bestseller and a New York Times Book Review editors’ choice. His new novel, Return to Valetto, is out now. More details at www.dominicsmith.net.