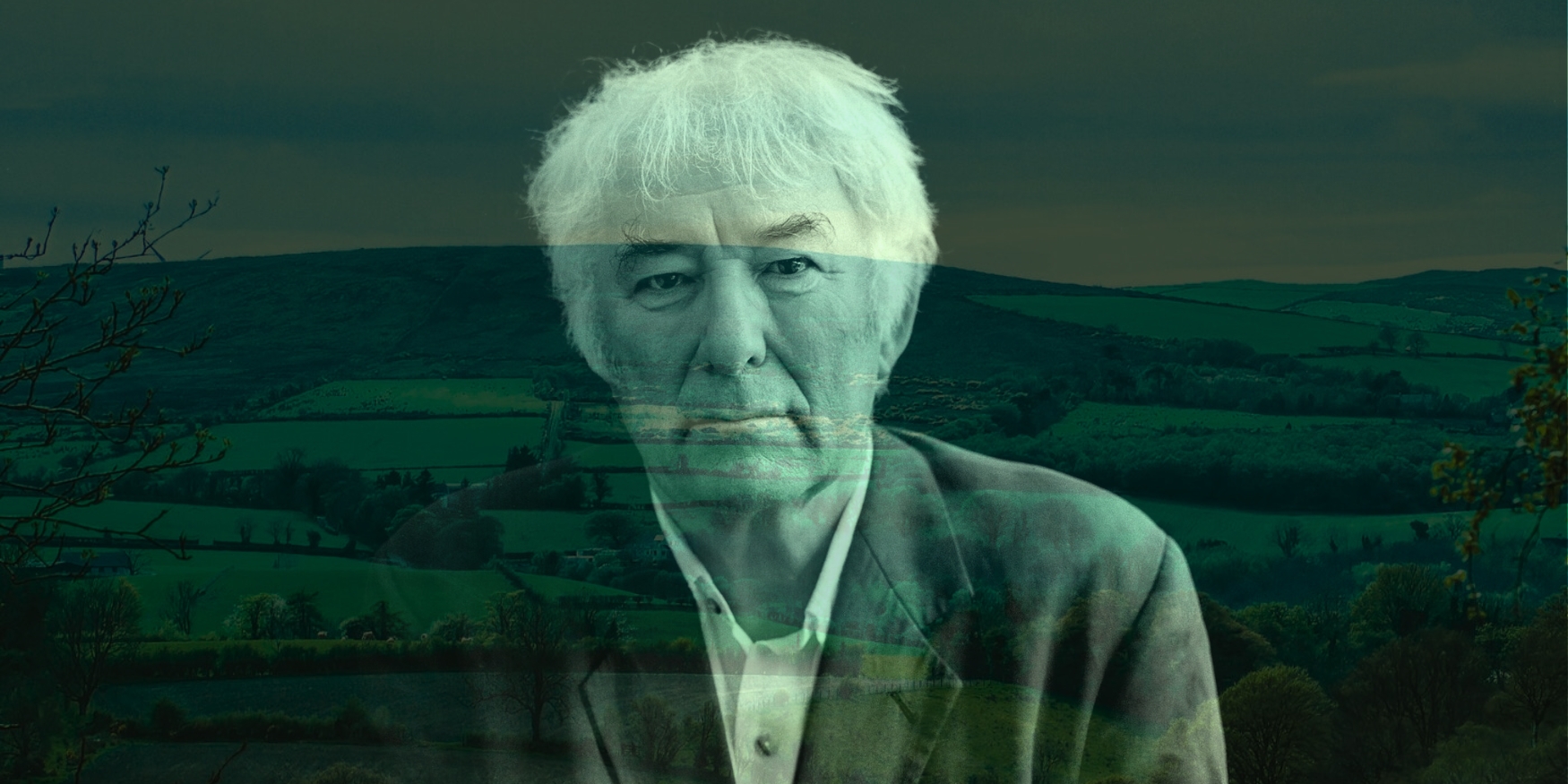

What Seamus Heaney Meant to Me, a Kid From Carrickfergus

Adrian McKinty on the Legacy of One of Ireland’s Great Poets

As an eager, new student at Oxford in the autumn of 1991 I had arrived early at the Examination Schools on High Street to hear Seamus Heaney’s latest lecture as the Professor of Poetry. These lectures were free but you had to queue as they were always packed out.

Heaney’s entrance was greeted with a reverent hush and then applause and he began by reading from his latest brilliant collection Seeing Things. The person sitting next to me that day was my flat-mate, Alicia Stallings, who, by one the vagaries of history, is now the current professor of poetry at Oxford. I myself became a novelist and perhaps like that famous Sex Pistols gig in Manchester, where everyone who saw them formed a band, everyone in the Examination Schools that day decided to become a writer.

The complete Poems of Seamus Heaney published late last year in the United States has been widely praised as a work of genius and has cemented Heaney’s status as one of the greatest poets of the last century. But, for someone from Northern Ireland he means so much more. I’ve known about Seamus Heaney my entire life. I grew up in Carrickfergus, County Antrim, only about 25 miles as the crow flies from where Heaney grew up in Bellaghy, County Derry. Born into a Catholic farming family Heaney’s early poems vibrate with the textures of that world: peat bogs, cattle marts, the rhythms of farm labour.

Seamus Heaney’s poetry has long been treated as a kind of sacred text in Ireland, recited in schools, memorialized in public spaces, and invoked whenever the island searches for language equal to its own complexity. During the Troubles, however—when Ulster spiraled into decades of political violence and communal fear—Heaney’s importance reached beyond literature. He became a moral and cultural touchstone: a figure who offered not answers but a way of seeing, a vocabulary for grief and endurance, even in the depths of despair.

Seamus Heaney’s poems were read in classrooms where children were growing up with soldiers patrolling their streets.

During the dark years of the 1970s and 1980s Heaney’s grounded, sensory language suddenly carried new weight. His poems distilled the tension between belonging and alienation, capturing a society where every day life persisted under the long shadow of armed checkpoints and simmering mistrust. He exposed the suffocating pressures that hemmed in public speech and private conscience. And he did it without succumbing to the crude binaries that fueled the conflict.

Heaney’s global stature also mattered. As his career soared—winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1995—he became one of the few Northern Irish voices whose work traveled far beyond the island. That international recognition helped ensure that Northern Ireland was not reduced, in the world’s eyes or its own, to a place of bombs and barricades. Heaney reminded global audiences that the North possessed not only conflict but also creativity. For many at home this brought a quiet pride: a sense that, even amid turmoil, our culture could produce beauty of universal resonance.

Heaney’s poems were read in classrooms where children were growing up with soldiers patrolling their streets. They were discussed in community centers where cross-community dialogue was fragile and rare. His language became a shared cultural reference point in a society where shared references were scarce. He offered a way for Protestants and Catholics alike to recognize themselves in art without feeling attacked or erased.

Heaney once described poetry as “the music of what happens.” During the Troubles, what happened was often brutal. But he believed poetry could also tune the ear to what might happen—what could happen—if people learned to imagine each other more generously

My last novel, Hang On St. Christopher, began with a poetry reading in Belfast that Heaney attends and which has nothing whatsoever to do with the story. Not a single critic of the book was struck by the incongruity of this failure in basic thriller plotting. That, I think, is because Northern Ireland boasts a dozen famous poets now and Belfast has become synonymous with verse and new writing. Belfast doesn’t just have Nobel prize winners in literature but fiction best sellers, Booker Prize Winners, TS Eliot and Pulitzer and Olivier Award winners etc. etc.

In his Nobel lecture in 1995 Heaney said poetry was “the ship and the anchor” of our spirit in a violent, divisive ocean. Heaney wrote poems about healing. He was an evangelist for the power of the poem as medicine. And even though peace has finally come to Northern Ireland our trouble world clearly needs Seamus Heaney’s words and lesson now more than ever.

Adrian McKinty

Adrian McKinty was born and grew up in Belfast, Northern Ireland. He is the author of the DI Duffy series of detective novels and the 2020 NYT bestseller, The Chain.