What Running Has Taught Me About Writing (and Vice Versa)

“Stay focused on what’s just ahead...”

I’m a daily runner. When I run varies, depending on the day’s contours, but I always lace up and head out. Earbuds in, audiobook on, running app ready to track my slow miles along semi-rural roads.

Often, I don’t want to go. No matter how much I practice, I find running difficult. When I was in my twenties, a doctor sent me off to physical therapy to help my terrible knees, cautioning me not to train for long distances—not to go above 10K—or I’d end up needing surgery by the time I was in my forties. (So far, so good.) But I’m not built for running, nor am I a natural athlete. What I do have: a reserve of willfulness and the desire to feel clearer, stronger. I wish I were faster and more capable, but my daily slog has become essential to my days. Some better part of me emerges.

I live on the outskirts of a small Vermont college town, near the Green Mountain National Forest. My street, which runs east into the mountains, is mostly lined with older homes, some ranging back to the 19th century. My apartment, the second floor of a renovated general store, overlooks a river and an old grist mill.

The surrounding neighborhoods are more modern, if still quiet—no sidewalks, but paved streets. Most often, I start out on nearby School House Hill Road (where, yes, there once was a schoolhouse), heading up a stretch of hill too narrow for two cars and bordered by a ledge of pines. At the hill’s crest is an old limestone quarry, along with clear views of Bread Loaf Mountain. From there, I choose either to go up another hill into a small winding neighborhood or to continue a mile down on School House to another neighborhood. I run variations on these loops through the neighborhoods while also running School House, the flat straightaway that connects them.

Stay focused on what’s just ahead: make this one paragraph good, then the next. Remain absorbed in the immediate moment.

My first mile is my slowest; my creaky joints need time to acclimate. I need to steel myself against my instinct that the run will be too much to get through. That first mile, I avoid checking my time at the start because I’ll be disheartened. I try to move and then keep moving. That first mile counts toward my total distance, but it’s also my warm-up. I use similar strategies to begin my writing day, often first retyping what I wrote the day before. This lets me avoid the blank page while also allowing me to rarify my prose and crack open my sentences, further consider my ideas.

The homes here are set back, and everywhere you look, pines and maples stand watch. It can be quaint. One family keeps two geese, who in warmer months sit serenely in a kiddie pool. And people are typically out for walks or tending to their yards. We almost all wave. This summer, I was running when I saw, far out, the blue beat of police lights, a firetruck, a car with its front crushed in. A man who works as a mechanic stood in his driveway. He was leaning against his tow truck, watching. I stopped. “What happened?” I asked.

He handed me his phone. He’d taken pictures of the car after its crash; somehow the driver had careened into a telephone pole. “Everyone’s okay,” he said, after I looked at the photos. “But maybe you should run somewhere else.”

We’d never spoken before. Afterward, I thought a lot about his decision to hand me his phone, the way we stood together, watchful, worried.

When writing, I struggle to stick with my thoughts, to figure out what’s going to happen next and how to narrate it—to make the many decisions that lead through a draft. To get myself through, I give myself a word count: 1,000 for the days I have more time; 500 for days I have less. I also give myself permission to explore an idea even if, in the exploration, my thinking gets convoluted or messy. A writing professor once said he believes in including things, an idea I take solace in. So I coach myself: it’s okay to include; I can delete things later; eventually I can reshape this into something more elegant.

*

The terrain where I run can be a little rough. A few houses are rundown, ramshackle—trash, bramble, and brush overrun the yards. (The strangest detritus: a rotting gazebo and a tattered flag depicting a bird with extended talons.) School House has an automotive shop on it, along with a hunting supply store (a gussied up shack semi-obscured in tree shadow). And stretches exist where no one lives. There, I spend my time considering the landscape, thinking about the crumbling stone walls at the woods’ edge—the evidence of farming over a century ago. Or I listen to the light rustle of birds and squirrels, or think, in winter, about the matte orange-red of wild holly bushes against the snow.

To get through my run, I think in terms of increments. I need to hit five miles, but first I stay focused on two—which feels more reasonable. I play tricks with my perspective. If I’m at two and a half, I avoid considering how I’ve still got half to go. Instead, I tell myself it’s only fifteen minutes until I hit four—and once I’ve hit four, I’m practically there. Generally, when I’m over twenty minutes in, I start to feel easier in my movement, able to pick up a little speed. This moment is similar to that point in writing when I believe I’m on to something: a few paragraphs come to me quickly, or I’ve learned something new about my story. Things begin to hum along.

I also have days in which nothing comes together, and the entire run is like wading through cement. And, at points, after hours of writing, I find I have almost nothing worth keeping; then I just want to throw my laptop out the window and into the river.

But I stay attentive to where I find pleasure in writing. I love language for its sonic qualities—its lifts and falls, its rhythms, its internal rhyme. As I’m working through my ideas about character, setting, plotting, another part of my mind is churning through sound, amusing itself. (The faster I type, the more assonance appears in my drafts.) Similarly, when running, I try to keep myself occupied by what I like—to keep that counterbalance. As I’m getting up a hill, my breathing turns ragged, but I’m listening to an audiobook, engaged by narrative. My body might resist the final mile, but beauty surrounds me. Recently, I was out mid-morning on a warm October day. The wind was up, and yellow leaves were in a slow drift down to the streets. Today, I was out late, and all was romantic gloom: just some bronze clinging to the trees, the light fading, and this mix of austerity and richness as bare branches revealed a rose-streaked sky at sunset.

*

During the pandemic, a new thought started to coalesce. I was seeing more people out: everyone was home; most were chattier than usual too. Several (more than several) remarked how they always saw me out running. One woman said, “Even when it’s snowing! The other day, I looked up and there you were! I said to my husband, ‘There she is again!’”

A man with apple trees in his front yard was out getting his mail. He asked, “How many years have you been doing this?”

“A few,” I said, jogging in place.

“Four or five, maybe.” The answer was just over five—when I’d moved to this area. He surprised me in knowing this. “And you go out twice a day?”

“Just once,” I said. “But the time varies. I’m also really slow.”

“Keep it up,” he told me and returned to his mail.

Sometimes I joke that I make running look hard. When I hear people say something encouraging, I just think they’re rooting for the underdog. But lately I’ve been trying to absorb what they’re saying: that they admire my practice.

I know I’m most preoccupied by my limitations. I want my writing to be stronger, brighter, shinier. With my debut story collection just published, my friends will say, “You wrote a book!” And I realize I need to be reminded of that—to focus on the accomplishment rather than dwelling on if my technique measures up; if the stories took a long time to get right; if the writing could just somehow be, ineffably, better. My nice neighbors also remind me to notice what they see—that all that effort, from the outside, looks like something good.

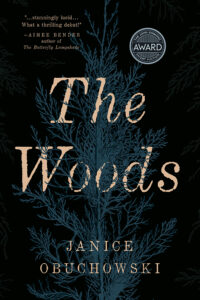

I wrote about this landscape and community over and over in The Woods, because every day my run reveals the metaphor and resonance all around me. Stay focused on what’s just ahead: make this one paragraph good, then the next. Remain absorbed in the immediate moment. When I’m writing, I most often think of these country roads—putting one foot down, then the other. On my best days, I gain clarity of thought, I calm. And those elusive moments also exist: when I feel strong and light, capable of sprinting forward.

__________________________________

The Woods: Stories by Janice Obuchowski is available via University of Iowa Press.

Janice Obuchowski

Janice Obuchowski’s fiction has appeared in Gettysburg Review, Crazyhorse, Alaska Quarterly Review, Story, Conjunctions online, and LitHub. Previously a fiction editor at New England Review, she lives in Middlebury, Vermont.