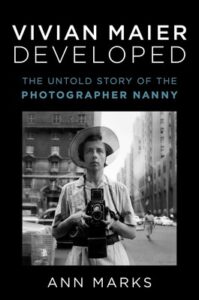

In 2007, 140,000 masterful images were discovered in the storage locker of a Chicago nanny and her work posthumously took the world by storm. It was not just the quality of Vivian Maier’s photographs that captured the imagination of admirers, but the mystery surrounding her life. Despite intensive investigation, no one could unravel her background or photographic motivations. Fifteen years later, the story of Vivian’s life and beginnings of photography can finally be told, starting with her 1951 summer employment in the Hamptons where she took pictures with a simple box camera.

Vivian’s Southampton pictures are notable for illustrating the stunning contrast between the haves and have-nots. Propelled by her keen interest in Native Americans, one day she chose to forgo the beach to cross over the tracks and meet members of the indigenous Shinnecock population who had long resided in town. She enthusiastically photographed them in pairs and clusters. Their sparse, tattered garb is markedly different from the Walkers’ fastidious frocks and bows, but the Shinnecock children are just as charming.

Many have observed that Vivian possessed an underdog’s perspective, and regardless of her circumstances, she identified primarily with the working class. While the beginnings of such an affiliation is apparent in her French photographs, this point of view would permeate her New York work. Possessing a progressive perspective, she was drawn toward capturing the intersections of race and class.

Attracted to difference and diversity, everyone mattered to Vivian.One day, 55-year-old Marie Jaussaud visited Vivian’s seaside workplace, most likely looking for a share of her daughter’s inheritance. Vivian took three portraits of her mother on the beach. Prints of one image, featuring Marie facing forward in a cap, were found both among Vivian’s possessions and at her cousin Sylvain Jaussaud’s residence in France. These are the only pictures of Marie discovered in Vivian’s entire archive. There is no record of mother and daughter ever meeting again.

Mother, Southampton, 1951, Vivian Maier

Mother, Southampton, 1951, Vivian Maier

While babysitting for the Southampton set, Vivian made connections for future employment, networking just as Eugenie had done. In November 1951, she traveled to Cuba, accompanying a family associated with the Fanjul and Rionda sugar dynasties. She must have been thrilled to make the trip, traveling to a place steeped in history on her employer’s dime and with the opportunity to tour as an insider. The journey included stops at beaches, sugar refineries, and “bateyes,” the communities set up for workers. Unused to photographing on the fly, Vivian mostly made exposures from a distance or in conditions of poor light. She posed families in front of their bungalows and children at school. Among the most engaging subjects from the excursion to Cuba were Carlos Fanjul’s playful rabbits.

Three wise rabbits, Cuba, 1951, Vivian Maier

Three wise rabbits, Cuba, 1951, Vivian Maier

A stint at the John Akin estate in Oyster Bay followed, where Vivian cared for sweet little Gwen, who grew up to be a photographer herself. Here she practiced techniques for shooting children that she would call on frequently in the future. She distracted the toddler with games, posed her in cardboard boxes, and stooped down to her level to chat and snap. On January 24, 1952, Vivian left their snowy lane to take in the Museum of Modern Art’s celebrated Five French Photographers exhibit. Here she scored the first of her celebrity conquests, shooting Salvador Dalí from below, just as she had a Cuban worker two months earlier, a technique that heightened each man’s presence. They face the camera appropriately outfitted for their disparate milieus, Dalí adding a bit of flourish via his trademark mustache. Vintage prints show that Vivian prepared a version that was cropped to cut off Dalí at the waist, but the resulting image lost much of its impact.

Left: Cuban worker, Cuba, 1951, Vivian Maier. Right: Salvador Dalí, NY, 1951, Vivian Maier

Left: Cuban worker, Cuba, 1951, Vivian Maier. Right: Salvador Dalí, NY, 1951, Vivian Maier

As Vivian’s employment opportunities moved to Manhattan, New York’s public parks became her picture-taking venues of choice, offering her interesting subject matter while watching the children in her care. Central Park served as a microcosm of the city where she could shoot the young and the old, the rich and the poor, the fashionable and the fringe. Attracted to difference and diversity, everyone mattered to Vivian. Her lens caught distinguished men in top hats and fedoras as they strolled briskly to appointments, as well as the downtrodden they passed on their way. Sleeping on park benches and in doorways, the destitute were dirty, ragged, and strung out, mostly oblivious to Vivian’s voyeurism. She didn’t hesitate to photograph them in such vulnerable states, ignoring their privacy in favor of her own artistry. Vivian made prints of the dichotomous men with somewhat crooked results, reflective of her learning curve.

The ins and outs, New York, 1951-1952, Vivian Maier

The ins and outs, New York, 1951-1952, Vivian Maier

Vivian frequently returned to the Upper East Side she had known as a teenager, and lived in the apartments on Sixty-Fourth Street between nanny stints. Emilie Haugmard still resided in the building, although after a handful of early pictures, she failed to reappear in the archive. For Vivian, this was home, a sentiment reflected by hundreds of exposures of the compound’s buildings, courtyards, and residents. She even photographed the exact apartment in which she had lived, inside and out.

Sixty-fourth Street apartments, New York, early 1950s, Vivian Maier

Sixty-fourth Street apartments, New York, early 1950s, Vivian Maier

While today these Upper East Side neighborhoods still encompass a range of household income levels, in the 1950s the differences were more extreme. The wealthy resided and shopped on the fancy avenues closer to Central Park, while the cooks, plumbers, maids, and seamstresses who served them were housed in tenements and public complexes to the east. Vivian had a foot in each world. She valued quality and style, and was the type of person who preferred one well-made item over ten cheap ones. Many errands took her to upscale Madison Avenue to bargain hunt for prestige brands and process film at Lugene Optical. Conversely, the laundromats, fruit stands, and liquor stores on First and Second Avenues appear in her portfolio by the scores.

Residing in a railroad flat around the corner from Vivian was a family with three sisters. Sophie Randazzo, the eldest, met Vivian in the neighborhood one day in 1951. They developed a fast friendship, but on Vivian’s terms: they only spent time together when she stopped by the Randazzo home for unannounced visits. The youngest sibling, Anna Randazzo, now in her eighties and living in Queens, is the only New York peer of Vivian’s who has ever been found. Sixty years later, answering an out-of-the-blue phone call, Anna offered a detailed description of her old friend, remembering she was masculine and cold, and wore flat men’s shoes and no jewelry or makeup. Her standard uniform was “a conservative brown tweed suit” and Vivian would “tug at her skirt to make sure her knees were covered.” In summer, her light cotton dresses were more flattering although she almost always wore a hat, even indoors. Anna never knew the last name of her big-boned and self-assured acquaintance.

Anna recalled that once her mother tried to welcome Vivian with a hug, but she pulled away with a curt “We don’t hug and kiss,” and then offered Mama Randazzo a handshake. The family found the young woman’s use of the royal “we” and distaste for physical contact quite striking. While Vivian was chatty and liked to gossip with the girls, she revealed little of her past, giving the impression that she had been born in France and was alone in the world. According to Anna, “She was a bit strange, but pleasant and polite—unless you said the wrong thing, and then she would jump down your throat.” When asked about her parents, Vivian’s retort was, “We don’t talk about that.” At first she carried a large camera, but later arrived with a smaller instrument slung around her neck. She never discussed her photographic aspirations, simply stating that she liked to take pictures. Nor did she ever mention that she worked as a nanny. As with most people whose lives intersected with Vivian’s, the Randazzos knew almost nothing about her.

On two fall Sundays in 1951, Vivian photographed the family in the natural light on their rooftop. While this was likely her first formal portraiture session, she was directive, confident, and in full command of events, conducting herself as a professional photographer. Anna described how Vivian instructed each of them, including her parents, where to sit or stand and how to pose. Requesting to shoot them individually, she sought to capture their unique personalities, which Anna feels she did effectively; Sophie was a dramatic jokester, Anna appeared shy and demure, and the middle Randazzo sister, Beatrice, posed like a would-be model. Vivian also fired off a single shot of the rooftop’s edge, the first of a photo collection of classic New York City tenements.

Up on the roof: Anna and Beatrice Randazzo, New York, 1951, Vivian Maier

Up on the roof: Anna and Beatrice Randazzo, New York, 1951, Vivian Maier

New York, 1951, Vivian Maier

New York, 1951, Vivian Maier

Vivian made two sets of prints from the sessions and gave copies to the family. While Anna was familiar with all the rooftop images, she had never viewed Vivian’s other work, but was not surprised to see grimy shots of vagrants taken at the same time as her family’s portraits. From the beginning, she had the distinct impression that their friend was fearless. Anna’s account corroborates that Vivian’s personality and behavior were firmly established by the time she took up photography: she was private, deftly diverting attention from herself and displaying an overt aversion to physical contact. She had already acquired the protective shell that would remain in place for the rest of her life. The Randazzo sisters were the only sustained girlfriends Vivian was ever known to have. Even so, after about twenty visits to their home, she never returned, the first of many sudden relationship exits.

In 1952, after the end of the school year, Vivian shifted from a long series of seasonal jobs to year-round employment caring for a self-possessed young girl named Joan on Manhattan’s Riverside Drive. Joan was an adventurous tomboy and thus an ideal subject, willing to pose with family, friends, and assorted strangers rounded up by her nanny. Much of the time she was hilariously attired as an Upper West Side cowgirl, despite a closet crammed with party dresses, which she wore with obvious disdain. The vivacious little girl served as a new muse for Vivian, who photographed her hundreds of times, using the results for printing and cropping experiments.

New York muse, 1952, Vivian Maier

New York muse, 1952, Vivian Maier

That summer, as the weather turned warm, Vivian’s pictures turned square: she had purchased an expensive, top-of-the-line camera. With unique features that were compatible with her aspirations and talents, the Rolleiflex changed everything.

Top photo: 1948 NYC directory; 1940 Census; Sophie Randazzo, New York 1951, Vivian Maier.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Vivian Maier Developed, published by Atria Books, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Ann Marks.