What Pornographic Literature Shows Us About Human Nature

Kathleen J. Woods on “Pain, Pleasure, and Want”

Years ago, as I muddled through early drafts of my porn book, a reader texted me one of my favorite pieces of feedback to date: “Weird boner.”

I was delighted less by the erection than the confusion—and the blunt encapsulation of arousal’s mysteries. How can we lust after something we find repulsive, offensive, or bizarre once we’ve come?

I am fascinated by pornographic literature’s uniquely immersive relationship to these questions, as articulated in Susan Sontag’s 1967 essay “The Pornographic Imagination”:

The physical sensations involuntarily produced…carry with them something that touches upon the reader’s whole experience of his humanity—and his limits as a personality and as a body. Pornography is one of the branches of literature… aiming at disorientation, at psychic dislocation.

In other words, pornographic literature expresses and explores (but never cleanly explains) what Sontag calls “an extreme [form] of consciousness that [transcends] social personality or psychological individuality.” In this state, moralities, memories, and other such trivial aspects of personhood are subsumed by sexual drive—a horniness powerful enough to eclipse the trauma, oppression, and ethical responsibility of which you might otherwise be consciously aware.

Given this foreclosure of self-knowledge, pornographic writers must be intentional in translating the extreme consciousness to the page. The tools most available to the writer are sense, sensation, and action, including speech. There can be no cohesive, reliable or pathologizing explication of behavior. Instead, the pornographic character expresses their will through the pursuit of lust’s release.

Pornographic literature is an expression of those parts of human experience that are defiant, recursive, and tangled.

But how to write that distance? How to navigate one of the most basic, slippery elements of fiction: point of view?

Pauline Réage’s 1954 classic of pornographic literature, Story of O, provides one model. Tracing O’s journey through desire for sexual submission and, ultimately, self-annihilation, Réage employs a shifting third-person perspective. This moves farthest outside O when she is least capable of thought or reflection, her consciousness suspended in pain, pleasure, and want.

Take, for example, the first visit to the sex château and the first time O is whipped, begs for a break, and is whipped harder. Here, Réage writes, “O might have assumed that to beg… for mercy would have been the surest method for making [her lover] redouble his cruelty.” That word “might” is working hard her, marking a barrier between the narration and what O actually assumes. We do not have access to her mind, and we cannot know whether that “redoubling of cruelty” is O’s fear or goal (or both).

However much this narrative distance obscures her conscious agency, it also implies that O is, at least temporarily, lost to her hunger for submission. Réage will utilize the same distance at the masked gala at the end of the novel, zooming out from an O who is now “of stone or wax, or rather some creature from another world,” ultimately transcended beyond personhood into an ether of lust. Her conscious, individual experience here is inarticulable, and, as there is no longer any “her” in this sexual fable, ultimately unimportant.

If we expect those passages that draw closest to O to provide greater insight, we will be disappointed, for Réage is ever coyly withholding, teasing that literary instinct to understand O while refusing rationalizing histories or diagnoses. O does not debate whether she enjoys submission but instead reflects on the fact of her confusing attraction to pain and pleasure. The few blips of memory offer no Freudian answer to her proclivities. Why did she want her adolescent crush’s “hematite ring” as “a choker”? Who cares! She did. Her consciousness is always drawn back to the fact of that desire. Such promises and withdrawals of illuminating introspection challenge the reader to, like O, “finally come to accept this constant and contradictory jumble” and believe her experience of a “happiness and deliverance.” We are not missing out on some epiphany; we are immersed in it.

Another case study in pornographic point of view is Samuel R. Delany’s Hogg (1969), which presents a far more challenging extreme consciousness with a far stricter adherence to narrative distance, underlined by a counterintuitive use of the first person. If Réage plays coy with psychic distance, Delany is obstinate. For roughly 250 pages, Hogg’s eleven-year-old narrator (called “cocksucker”) details filth, violence, and genitalia with visceral specificity and affective detachment. For example, one penis is “a wrinkled nozzle with a vein up the side” which “[squirts] greasy juice.” This is, as Delany himself has said, “not a nice book.”

In part, the novel is driven by this disorienting tension between the distress we might expect from a child mired in sexual gore and the unflinching, unconflicted account on the page. Cocksucker doesn’t have any dialogue until book’s closing line, when he is asked what he’s thinking about and responds, “Nothin’.” His narration provides flickers of access into his thoughts and emotions, but hardly sheds light on his motivations or psyche, and it is a mistake to believe that it will. Still, playing on the distance demanded by porn and the access promised by the first person, Delany sprinkles “I wanted” or “which made me feel funny” or “I was scared” like breadcrumbs, coaxing the reader through forests of murder and rape. Then, with one-third of the novel remaining, we arrive at something truly shocking: a flashback!

Fleeing from an unknown pursuer, cocksucker narrates, “About a year ago, two guys together caught me and took me to some burned-out building… Most of the things they did with me I didn’t like at all. And it took me three days before I got away.” Of course this child, even younger then, did not like being kidnapped. Of course his memory inspires flight now. Those “things” must have been horrible! At last, he is knowable, his wants and actions cohesive, aligned with polite expectation. Further, through this memory, some of the promised access of first person is fulfilled. But any release felt here is complicated—are we glad this child can suffer after all?

Ultimately, though, such a realist interpretation forgets the pornographic project. Immediately before that conclusive “nothin,” Delany provides over one page of access to cocksucker’s thoughts. After identifying with his Blackness for the first time, he recalls how those kidnappers in the burned-out building called him racial slurs, which he “kind of liked.” But they also said, “they really loved [him]…and wouldn’t let [him] suck [them] off or pee on [him],” which made him feel “dirty and helpless and really scared.”

What else did the reader expect? Delany manipulates the first person to tease some recognizable trauma or moral reckoning only to emphasize the denial the pornographic genre demands. The mystery of the narrator’s “extreme consciousness” is affirmed. It is for us to experience, not understand.

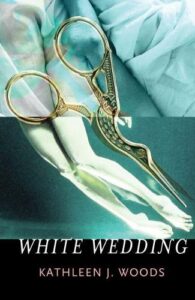

And so we return to “weird boner.” As a writer, I was drawn to pornography’s refusal of revelatory interiority, which formally questions how comprehendible desire and pleasure even are. In conceiving White Wedding’s nameless woman, I was uninterested in shame, turmoil, and those wells of trauma so often used to frame queer narratives and/or “solve” a female character’s pursuit of sex. I imagined her unmoored from linear time and unconcerned with any assumed guardianship of sexual morality. This was cathartic.

However, in studying O and cocksucker and writing the woman, I also encountered a compelling impossibility inherent to the project of pornographic literature, or at least one personal challenge.

Pornography deals with both the dislocated psyche and the purely embodied experience. To what extent can these bodies escape sexed, gendered, and racialized readings? And those sexual psyches transcend sexed, gendered, and racialized experiences, from oppressions to joys? When it comes to pornographic point of view, it seems absurdly reductive to view O only through her white female adulthood and cocksucker through his often-white-perceived Black male barely-adolescence, but also a mistake to ignore how other characters see and respond to them. How the degree to which their bodies conform and transgress influences where and how they move, meeting how much resistance, sensing and seizing which material aspects of their worlds (for example, take O’s French châteaux and fashion magazines; Hogg’s American truck stops and docks). Even the sexual acts those bodies perform.

For myself, wrestling with the complications of refusal and response—or perhaps reflection—is not the problem but the point. Acknowledging the complex textures of lived experience welcomes rather than rejects mystery, disrupting any singular answer for arousal. Pornographic literature is an expression of those parts of human experience that are defiant, recursive, and tangled. How those knots excite.

__________________________________

White Wedding by Kathleen J. Woods is available via FC2.

Kathleen J. Woods

Kathleen J. Woods earned an M.F.A in Creative Writing from the University of Colorado at Boulder, where she served as Managing Editor for the journal Timber. She was a 2018 Writers Grotto fellow and will begin teaching with Left Margin LIT this spring. Her stories and essays have appeared in Bitch, Western Humanities Review, Apeiron Review, and others. White Wedding is her first novel.