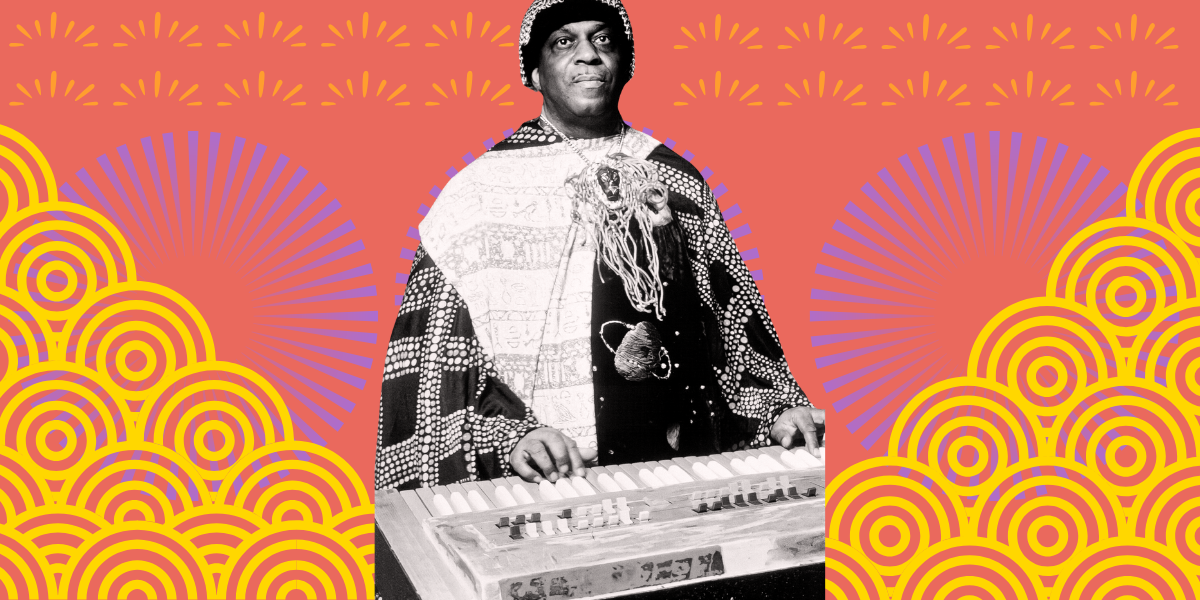

What Playing With Sun Ra in College Taught Me About Myself

Michael Lowenthal on Jazz, Musicianship, and Discovering the Limits of Improvisation

Sun Ra claimed to hail from Saturn, but he and his far-out band, the Intergalactic Arkestra, still suffered the hassles of earthly travel. Because of a snafu, they would arrive on campus a day early, before their hotel expected them. His agent, in a panic, called our group’s director. Could we help him rustle up some beds?

We were Barbary Coast, the Dartmouth College jazz band. Every winter, our director invited in a guest musician—Max Roach, Slide Hampton, Lester Bowie—who’d teach us for a week and guide us in a Saturday-night performance. Each of them had mastered the master-class circuit; none had needed help with where to sleep.

We turned to Adam, our piano player, who lived in an old frat house called Panarchy. Bucking its Greek identity, the house had become a refuge for students too weird to fit in at our tight-assed WASPy school. Adam told his fellow Panarchists about our bind, and they were stoked to host one of the world’s wildest bands. Mattresses and questionably clean bedding were dredged up, dusty couches cleared of detritus. Adam’s girlfriend, Angela, commandeered the kitchen, churning out hundreds of dumplings for dinner.

I must have come late, because I found my bandmates already cross-legged on the floor, gazing up at an armchair in which, as if enthroned, sat Sun Ra. He looked like no entity I had ever encountered. Said to be seventy-five, he seemed a hundred, until I peered closer: childlike, impulsive eyes; puffy cheeks. His goatee was dyed an uncanny shade of orange, that of a Dinka tribesman’s hair or maybe a punk’s mohawk. His bulk, shrouded in a floor-length poncho, appeared almost weightless, ectoplasmic.

“…get the planet ready for space beings,” he was saying. “People need to be tuned up. They’re out of tune with the universe. That’s why they have to hear my songs: cosmos songs.”

His voice came in lispy, whispered bursts; we all leaned in.

“My music is power-ful,” he went on. “Few months back, we played some gigs behind the Iron Curtain.” This was the very start of 1990. “And?” he said. “What happened? Y’all saw: the Wall came down!”

On and on he speechified, his brown skin purpling as his vehemence increased: history versus mystery—his story, my story—knowledge of the ancient unknowns…Part lecture, part homily, or maybe schoolyard brag, his spiel was both baffling and bewitching. The other Arkestra members (he’d come with eight or nine) hovered at the room’s margin, gobbling dumplings, chiming in with the “Mm-hmm” or “That’s right!” you’d hear at a Baptist church.

I’d assumed that fitting in required changing yourself. But Sun Ra said: Change the space around you.

And the students at Sun Ra’s feet? Some were nodding, brows furrowed, as if in a foreign-language class; others were trying not to bust up laughing.

Sun Ra had never done a college stint like this, let alone at a place as conventional as Dartmouth. Even at Panarchy, you could sense the instant culture clash. Sun Ra looked as comfortable as a parrot in the Arctic.

Or maybe I was projecting.

At twenty, I’d played the trumpet for fully half my life: thousands of hours of embouchure training and finger drills and scales. I was proficient, and loved to play, but what I truly excelled at was excelling; musical discipline was part of my whole strive-for-straight-A’s MO. But now, four months from graduating, I wondered how the trumpet would fit in my new life. Without the structure of school, without the earning of brownie points, would musical achievement lose its meaning?

Really, I was wondering about much more than the horn. The striver in me had increasingly been losing faith in the worlds I’d sought praise from. Coming out as gay had sealed my distrust of standard power structures, and landing at the top of my class seemed to cast doubt on my integrity: fishy to succeed within the very system I questioned. The compass I’d been steering by had scrambled; did I need a new north?

Enter Sun Ra, brimming with eccentric insurrection, claiming his music’s power to topple walls. He kindled in me a combination of skepticism and jealousy: I didn’t think I wanted to believe what he believed, but he sure made me long to believe something.

Sun Ra was a visionary, according to our director, Don. In the 1940s, going by his birth name, Herman Blount, he’d played in Chicago with the famed big-band leader Fletcher Henderson. Then, in the ’50s, proclaiming he’d had an out-of-body experience in space, he transformed into Le Sony’r Ra—or Le Sun Ra, or Sun Ra—and started making “music of the spheres.”

A pioneer in using rhythm machines and synthesizers, he’d put out maybe two hundred albums, revered by a range of artists, from Herbie Hancock to Sonic Youth. He and his “Arkestra” had toured the world, performing in flamboyant robes and floppy wizard’s caps.

“It’s a kind of cosmological cult,” Don had told us, the day he announced Sun Ra’s visit. “Science fiction mixed with ancient lore, Egyptology.”

“What about this coming-from-Saturn stuff?” Adam asked. “Are we supposed to think that’s true? Does he?”

“I don’t know,” said Don. “Does it matter?”

Then he told us how he thought about it: Imagine growing up in the 1920s and ’30s. A dreamy boy, a musical genius, different from all your peers. A dreamy Black boy—in Birmingham, Alabama. Brutal Jim Crow segregation. Lynchings. That boy—Herman—looked around, saw that there was literally no place in that world for him, and decided he was “not of this earth.”

“Maybe it’s a myth,” said Don. “Or maybe a kind of drag. But who’s to say it’s any less true than what’s beneath the costume?”

The band was quiet. Everyone looked as hesitant as I felt.

Don said, “If it’s not your thing, don’t get stuck on the ‘spacey’ stuff. The music is what’s really out of this world.”

Normally, in advance of his visit, the guest would send us charts: full arrangements, with parts for trumpets, saxes, ’bones, and so on. But Sun Ra demurred; first, he said, he had to see what we looked like.

Don mailed him a photograph. We waited.

A curiously thin packet finally came. He’d sent a dozen single sheets; on each was scrawled a title and an unadorned melody, like jingles from a kindergarten songbook. Had Sun Ra clocked our strait-laced looks—and seen that all but one of us were white—and thought this was as much as we could handle? Don phoned and asked what we should do.

The pages turned out to be the alto sax parts. Sun Ra said to transpose them for every other instrument. “Then play ’em all in unison. Real slow.”

Dutifully we plodded through the simple melodies. The longer we rehearsed them, the less sense they made, like words repeated so often they crumble into nonsense. Was this some kind of avant-garde joke?

My doubts about Sun Ra mirrored qualms I had about the very nature of jazz. My childhood trumpet training had been classical: right notes vs. wrong. Later, in high school, when I had first tried jazz, I found improvisation terrifying. If all the notes were mine to choose, how could I ever know I got them right?

I fashioned an escape hatch: whenever my part called for an open trumpet solo, I’d go home, compose some riffs and practice them to death, then perform this faux improvisation at the concert. Eventually, obeying the music’s letter if not its spirit, I rose to the rank of first trumpet. I even made the all-state jazz ensemble.

Then I scored a spot in Barbary Coast. The music was intimidating—funk and bebop, Afro-Caribbean—but Don was patient, somehow both meticulous and mellow. He pushed us toward ad-libbing, and I embraced the challenge: boning up on blues scales, rehearsing rhythm changes, hoping to make up in perseverance for what I lacked in feel. By senior year, most of the time, I could ad-lib adequately, without leaving behind a song in ruins.

Adequately. Does any word in the language have less jazz?

Tuesday evening, when I arrived for our first rehearsal, Sun Ra was sitting at the piano. He wore the same poncho, and also a woolen skullcap. He seemed subdued. It turned out he’d stayed at the hotel after all (Don had found the last available room), while the other Arkestra members had partied at Panarchy, shooting pool until dawn. Three of them had crashed on the floor in Adam’s room—he’d woken at six to find them passing around a bottle of wine, saying, “Hey, now, give me some of that mouthwash!”

At the piano, Sun Ra looked to be in a kind of exile. Someone should be tending to him, I thought…but not me. I feared getting closer, nervous that he’d sniff my doubts—about him, and about myself. He plinked around on the keyboard, then smiled arcanely. Time to start, he said.

His voice was barely audible. A song with “space” in the title? That hardly narrowed it down: he’d sent tunes called “Island in Space,” “Sons of the Space Age,” “Spacelore.” I was searching through my folder when he mumbled, “One-two-three-four-five-six-seven-and—”

I whipped my trumpet up to my lips in time to muff a note. A beat later, a sax squawked, and then the trombones.

Sun Ra let his hands go still, and all of us stopped playing. He gazed up, away, as if to a distant nebula, and then, in a voice as thin as tracing paper, went, “One-two-three-four-five-six-seven-and—”

Now we came in together, but all at different speeds.

Beside me stood Laura, our trumpet virtuoso, a freshman who played with silky sophistication. “Excuse me, um…sir?” she said. (She and I had debated: Should we call our guest Mr. Ra? Mr. Sun?) “Excuse me,” she said again. “Can I ask something?”

Sun Ra looked more or less at her.

“When we rehearsed,” she said, “we did this four times slower.”

He seemed to consider this. He nodded.

“But now you’re counting it off super-fast. Which way’s better?”

A gleam livened his eyes. He was a jester playing a bodhisattva, or vice versa. “Depends,” he said, “on what you want to hear.”

The rest of the rehearsal was only more unnerving. Pronouncements blazed forth from him but evanesced, leaving only contrails. The Arkestra members tried to guide us: Marshall Allen hunkering with the saxes, counting rhythms, Michael Ray kibitzing with us horns. “Watch his face,” Michael said. “Always just keep watching. Anything else, I’ll be here to translate.”

Translate seemed too tame a word. I gave up and slumped onto a stool.

“Listen!”

It was Sun Ra, his voice aimed at me. I looked into his dark, dilated gaze.

“Your ear’s a harp,” he said. “A harp made of strings. My music vibrates strings in there that never moved before. It’s gonna make your head hurt. Don’t worry.” With that, he stood and shuffled to the door.

I should have stayed with my bandmates; there would be strength in bellyaching together. But I was so wrung out, I just packed up my horn and took off.

In the bitter New Hampshire night, my skull ached with tight, tectonic pressure. Depends on what you want to hear, he’d said—an empty riddle. As if wanting were all success required. I stomped home, mad at him and madder at myself (why should I let this total quack tip me off my hinges?). I crunched snow in a steady, stringent beat.

The second rehearsal didn’t go much better.

Sun Ra had decided against playing the tunes we’d practiced. Instead, he’d spent the day composing new material.

Jothan Callins, another Arkestra trumpeter, tried to calm us: Sun Ra did this every day, and used the date for a title. During a concert, he might call out, say, “April 6,” and you’d have to locate that date’s tune.

Jothan seemed agreeably nerdy—less astro-jazzman than small-town postal clerk—but his attempt at reassurance backfired. If at first I’d felt the rug was being pulled from under me, now I doubted there’d ever been a rug.

Sun Ra played each section’s part, then asked us to play it back by ear. Without written notes to follow, I flailed. Laura managed to jot the trumpet part into a notebook, but by then, Sun Ra’s riffs had changed.

After an hour, it was time to try our parts together. Sun Ra counted off, and we came in.

Disaster. A multicar pileup.

What he hadn’t explained was that he’d written the parts in conflicting time signatures: saxes and trumpets in 4/4 time, drums and bass in 3/4, piano in 7/4, ’bones in 5/4. He seemed peeved we hadn’t figured it out. “Not just that you’re playing wrong,” he said, “it’s that you’re thinking wrong. Exercise the muscles of your brain!”

Afterward, I battled a headache twice as sharp as the previous day’s.

The next rehearsal was Friday, a day until the show. Surprise, surprise—Sun Ra opened more musical cans of worms: songs that, for all we knew, he was making up on the spot. Diplomatically, Don suggested we work on tunes we’d played before.

“Y’all seem so worried,” said Sun Ra, “about playing the notes. But you can play more than just notes on a page, you know. You can play the river. You can play the sun rays.”

What a cop-out, I thought. If anything goes, nothing needs perfecting.

But fine. He was the visionary.

And so, during the next song, I decided to beat him at his own game. I came in a millisecond ahead of or behind each note. I’d like to say I did this out of open-mindedness, but cussedness was closer to the truth.

Strangely, my mischief-making failed to wreck the music. For every phrase I sabotaged, Sun Ra changed his playing, widening the song’s sidelines to keep my notes in bounds. You’re right, it’s a game, the man seemed to be saying, but all of us are on the same team.

We moved on to a stumper of a song called “Friendly Galaxy.” Before, I’d been thrown by its herky-jerky melody, but now I let my knees and shoulders act as shock absorbers, and found I could bodysurf the song.

Among the band, a fissure formed: who was in on the music’s fun, who wasn’t.

Sun Ra wrote a vamp that the saxes couldn’t seem to learn. “The problem,” he declared, “is you don’t want to know it. The ’bones look like they do. Let them try.”

Matt, an Asian studies major, led the trombone section. Pale and blond, as placidly compassionate as a chaplain, he huddled with Pete, a toothy, earnest grad student in chemistry. It was hard to picture two less probable avant-gardists, but after some transposition, they both nailed the vamp.

Adam, on piano, also found the groove. “See?” said Sun Ra. “He used his ears. Just like Jesus Christ did. Used his ears and listened to the people.”

Sun Ra’s patter was growing only weirder. The less I took him seriously, the more seriously I could take him—which seemed, to my delight, like one of his own riddles.

It was still unclear how we’d throw a show together, but after rehearsal I was buoyant with imagined Sun Ra-isms: The less you grasp for something, the more you’ll come to grasp it. The less you think you know, the more you know.

I was halfway home before I noticed I didn’t have a headache.

Sound checks were normally just a quick test of the mikes. But Saturday afternoon, Sun Ra, wearing a huge Russian-style fur hat, launched another full-scale rehearsal. Now that he’d begun to get a sense of us, he said, he was matching the songs to our “vibrations.”

Sun Ra had believed—and made me, too, believe—that he’d awoken a cosmic spirit within me, but maybe what he’d triggered was my same-old striving self.

Discontent began to percolate among the band. Sun Ra didn’t notice, or didn’t care. The check stretched beyond an hour. Then two.

The first to leave was Laura. She muttered something, maybe an excuse about homework, and stalked offstage. Jothan asked what the trouble was. Way too long, I told him.

“Two hours? That’s nothing,” he said. The Arkestra often practiced for fifteen. “Night or day,” he added, “Sonny can call rehearsal. You just have to be there. Be ready.”

Maybe that worked for the Arkestra, but not for Barbary Coast: minutes later, another defection, and soon a steady stream, until more than a third of the band had bolted. Now Sun Ra couldn’t help but notice. He looked like a Santa Claus, tired from hauling gifts, who’d learned none of the children liked his toys.

Well, maybe not none. Matt and Pete had stuck around to rat-a-tat their vamp. Were they truly digging the style or just being charitable?

I found myself, for the first time, feeling bad for Sun Ra. The week here must have been as hard for him as it was for us—harder, maybe, since he was on our turf. I considered what Don had said about Sun Ra seeing he had no place in the world around him. I’d often felt that way, too, in my family and also here on our beer-and-frat-boys campus. I’d assumed that fitting in required changing yourself. But Sun Ra said: Change the space around you.

I stayed for the whole sound check. I had started to like his music—or to like the notion that I could like it.

For guest-artist concerts, we split the night in two: first set by the Coast and our guest, second by the guest and his own group. I wish I could remember the first set more sharply, but the shock of the second half has skewed my recollections, like wall-hung art rattled by an earthquake.

Feeling encased in a body cast of nerves: that I remember. Nerves for myself but also for the band, considering all the walkouts during sound check. But once we took our places onstage, everyone found their manners. (Laura had even purchased a multicolored cap and donned it now with good sportsmanship.) If anything, we all behaved too well—Sun Ra included.

He strutted out in a gold lamé cape and bejeweled velvet hat—they looked nicked from a Renaissance Faire—and gave the crowd a Grand Panjandrum bow. But then, when he turned around and sat at the piano, he sent us an anxious-looking grin. At the time, I supposed he worried we’d make him look the fool, but now I wonder: Did he worry he’d make us look bad? He played the first tune timidly, and so we inched out after him onto the music’s tightrope, everyone scared of knocking the others off.

It was Michael Ray who cut the tension. (Along with Marshall and Jothan, he was sitting in on our set.) On “Love in Outer Space,” he pranced about the stage, crooning with evangelical or maybe self-mocking charm: “Sunrise! Love for the world to see. Sunrise in outer space. Love for every face!” When he soloed, he screeched a streak of higher and higher notes, pretending to tug one leg up on a long invisible string, as if his leg’s rise controlled the music’s.

Oh, right, I thought. The point is to have fun!

And we did, for the rest of the set, an aural tickle fight that drowned out the memory of rehearsals. After our last tune, Sun Ra seemed pleased. Or not displeased. Relieved?

I was too: I’d played well, I’d let myself enjoy it. We followed Don downstairs to our practice room, high-fiving.

I had buffed my trumpet and laid it in its case—antsy to claim a seat for the next set—when Michael Ray materialized at the door. After a brief consultation with Don, he beckoned to me and Matt and Pete.

Michael was now in costume—orange tunic, satin dunce cap studded with ruby sequins—transformed by his garments, like a priest. “Grab your horns,” he said. “Sonny wants to see you.”

No time to gauge the other students’ reactions. (Envy, I’d guess, in equal measure with pity.) We scrambled upstairs, into Sun Ra’s dressing room. Surrounding him were acolytes who tinkered with his outfit. Piles of composition paper spilled from old satchels. On the table: a battered Disney songbook.

He said nothing but somehow used his silence to convey that we were meant to join him for his set.

If I’d been taut with nerves before, now I was unstrung. On noodle legs, I stepped back onstage. The Arkestra’s ranks had doubled with late-arriving veterans: June Tyson, vocalist and dancing violinist; John Gilmore, so inventive a tenor saxophonist that John Coltrane had asked him for lessons.

At last Sun Ra sashayed onstage. He raised his arms (but wait, I thought, what music are we playing?), then whap!—whipped his hand at the air, as if swatting an insect; the band, at the instant of the phantom insect’s doom, pounded out a massive, motley chord. Without quite having known it, I was playing too. How had I chosen my note? No idea.

When Sun Ra hurled his hand again, we struck another chord. Every player had chosen a new note, no one had consulted, and yet the sound was ringingly coherent.

Sun Ra twirled, his arms and wrists as fluid as a showgirl’s. Pa!—he flung his fingers, now like someone shooting craps—pa! pa!—with each fling, we forged a different chord. Even the notes that shouldn’t have fit within each cluster did. Dissonance and harmony, consonance and clash: the sound kept swallowing its own tail.

I felt attached to the band, like one foot of a centipede: as it moved, so I must move; as I moved, so must it. The song—if that was what it was—tumbled toward a climax, Sun Ra’s antic directions arriving ever faster, until shh! His arms shot down; the Arkestra cut to hush; the hall tremored with complicated silence.

I would have liked to bask in it, but Sun Ra now started banging something on the piano, and Jothan whispered, “Watch. Follow me.” Sun Ra’s intro wandered, appealingly arrhythmic. Then a frenzy as all the players rifled through their music. (Had they caught a signal I had missed?) Just in time, Jothan slapped a page onto the music stand we shared.

Soon the song evolved into a daisy chain of solos. Gilmore’s tenor gushed, demonically divine. Next went Marshall Allen, hands on his sax like feral scrabbling mice.

I almost didn’t notice Jothan jabbing at my arm. Crap. Had I missed another cue? I dared a glance at Sun Ra, whose eyebrows waggled minutely in my direction.

Jothan said, “It’s you. It’s your solo.”

His smile brought to mind his statement yesterday: You just have to be there. Be ready. How often, attempting jazz, had I failed to do that? Terror trampled through me, but there was no time to fret: Sun Ra had shoved me off the ledge, and now I fell and fell and—

Whoa…

I floated!

A fresh feeling: pregnant with pure space. Nothing for me to do now but fill that space with sound. Instead of trying to live up to a music I’d heard before, I decided just to play, and found out that I could. I played, splendidly dazed, until I knew to stop. The song swept on. Now I swam within it.

The next tune was new to me: a cross between a Count Basie stomp and a Sesame Street rhyme. The band danced in a conga line, up into the crowd, singing the admonitory lyrics:

What do you do when you know that you know

that you know that you’re wrong?

You’ve got to face the music!

You’ve got to listen to the Cosmos Song!

As we sang, Sun Ra chanted a descant from the piano: “You in the Space Age now…ain’t no place you can run…you can’t run away…Space Age is here to stay…”

The band paraded on, daffily proselytizing: Face the music!

At some point, Jothan told us students we were done. Back in the dressing room, we hugged and pumped our fists.

I was giddy with disbelief, with pride at my ad-libbed breakthrough. I grabbed a pencil, an unmarked sheet of composition paper. “I’m not sure I could say I’ve been to Saturn,” I wrote. “But tonight, playing with you, came close. Thank you. Your music has changed my life.”

I slipped the note into the middle of Sun Ra’s Disney songbook.

I was eager to carry something of Sun Ra forward with me, but it was hard to keep hold of my bliss. The all-involving week with him had left me so behind—I hadn’t touched the thesis I was writing—that I could focus only on catching up.

I was on a Senior Fellowship: a year free from courses, in order to pursue my own project. I’d applied in a tantrum of frustration, claiming to be sickened by the academic treadmill, but maybe, too—if I’d been honest—sickened by my talent for sprinting on it. I’d proposed to write a novel, promising a draft by year’s end.

Writing a novel, it shocked me to learn, involved its own drudge work. In fact, as the year progressed, my thesis had come to seem like a classic office job. Every day, I sat at my desk and poked some words around: less like bolts of inspiration, more like nuts and bolts. Should this have been a disappointment? Was it?

For now, I had to knuckle down and grind out the novel’s ending—a big task on a bigger list for my last months at school: print an issue of our queer newspaper; plan a radical alternative commencement; prepare for the Coast’s Senior Show.

I was thinking only about that show—what song to choose—when I arrived at rehearsal a month later. But Don pulled me aside with Matt and Pete. Sun Ra’s agent had called, he said. Something about a secret message, stuffed inside a book? The Arkestra was heading out on tour soon, to Europe, and Sonny wanted the three of us to join him.

“Oh, my gosh,” said Matt.

Pete said, “That’s insane!”

Dorkily, we danced around the room.

After we’d calmed down, Don divulged the hitch: the tour would take us away for the school year’s last weeks, meaning we would miss exams and also all the end-of-college parties. Dartmouth students simply didn’t do that.

“But we have to,” I said. “Don’t we have to?”

One last thing, said Don: the agent had mentioned a show in Boston. Could we play that gig first, a warm-up for the tour?

Yes, we said. Yes to it all. It was in our stars.

The day of the concert, I wore what passed for wild within my wardrobe: a faded purple button-down, a Guatemalan patchwork vest. Matt picked me up for the two-hour drive to Boston (where Pete, going separately, would meet us).

The ride to Boston was always a culture shock—speeding from our sheltered, rural campus to the city—but this time, it launched us toward an inconceivable distance. What new worlds would Sun Ra show us? Who would I end up being?

We headed to an address at Northeastern University. A group of students were waiting for a promised preshow workshop, but the Arkestra, they told us, was nowhere to be found. Uncertainly, we joined them in their vigil.

Evening fast approached; still, we waited. Could we have been roped in to a conceptual performance? Maybe to one-up John Cage and his infamous four minutes, thirty-three seconds of silence, Sun Ra had composed a piece for a band that never comes.

Half an hour before showtime, a bus pulled up and out straggled the bleary-looking Arkestra. Jothan saw us and shook our hands, as did Michael Ray, but Sun Ra scuffled by with an air of depthless blankness.

Matt and I tailed the band backstage. Had Sun Ra forgotten his invitation or, worse, had a change of heart? Panicking, I wondered if I’d done something (my purple shirt?) to prove I was unworthy. When Pete arrived, we didn’t know what to tell him.

The show was already twenty minutes past curtain time when we were ushered over to Sun Ra, who sat in a love seat, pasha-like, a heap of garments before him. June Tyson, the vocalist, picked out a robe for me. No, too short, said Sun Ra: “Can’t be ‘earth clothes’ showing.” Finally, he consented to a baggy saffron toga and a purple toque that made me look like one of the Seven Dwarves.

I felt silly, but Sun Ra’s solemnness kept me from cracking up. In truth, I wanted not to laugh; I wanted to be transformed.

Sun Ra’s aides helped him up, and we all followed him out into the lights. The hall was rife, I knew, with jazz cognoscenti: students from nearby Berklee College and the New England Conservatory, who’d mastered more music theory than I had ever heard of. But I was the one onstage. I tried to look convinced.

The show was a volcano: creating itself out of itself, all flow. A smash of drums, a piling-on of horns. Meanwhile, an oldish guy (Art Jenkins, I later learned) skulked around, acting out some cryptic melodrama. He “sang” in the spookiest, most sublime voice I’d ever heard, a goblin with a tracheostomy tube.

Sun Ra was simultaneously impish and imperious, bossing us with wiggles of his hands. He played behind his back, with his elbows, his knuckles—the man was having furious fun.

At last came a moment I’d hoped for and dreaded: Sun Ra gave me the scantest wink; I lifted my horn to solo. But Michael Ray elbowed me. “Not here. Go up front.”

Alive with fear, my skin throbbing, I threaded my way forward and peered into the crowd: a black void. Could they see past my costume, inside, to the iffy impostor? Behind me, the drummers beat an ominous jungle soundtrack. I answered with some anxiously honest notes.

Soon I heard another horn, and spun to find Jothan, aiming his riffs at me like a lance. I aimed my own notes back, and we jousted. A spotlight hit us, or maybe I imagined that toasty glow. The crowd cheered—grading on a curve, was my first thought. But they didn’t know I was just a student.

I liked to think of myself as offbeat; now that I was starting the open solo of adulthood, I had to face the truth of my own music.

The rest of the show, I rode a stream of jittery amusement, juiced by the inch-close risk of failure. We played Sun Ra’s undulating take on a Chopin prelude, a Wes Montgomery cover, cosmic jazz. Miraculously, I managed to keep pace.

A gust of applause ended the show, strong enough to blow us out into the Boston night. The Arkestra said to chum along, the party was only starting. The name of the place we ended up, Café Amalfi, rang with all the glamour of the world I now guessed I might be part of.

The next day’s Boston Globe had nothing about the show. The keenness of my letdown was dismaying.

But the following morning, there it was: “Sun Ra and his Arkestra play some imaginative originals and a few surprises.”

I skimmed past the praise for Marshall Allen’s flute work and zeroed in on a line I immediately learned by heart: “Aside from one sideman dancing with a black ventriloquist’s dummy, the most surprising visual aspect was the presence of three Caucasians in what has heretofore been a resolutely nonwhite ensemble.”

I loved the line’s loftiness: confirmation that what we’d done might be as momentous as I hoped.

Don would later say Sun Ra’s visit changed his life. When Michael Ray formed an Arkestra offshoot, the Cosmic Krewe, he asked Don (who’d mostly been teaching, and not performing, for years) to play “jazz funk of the future” on trombone.

Adam, on whose bedroom floor the Arkestra had crashed, also joined the Cosmic Krewe and became a full-time pianist, including tours as a US State Department “Jazz Ambassador.”

Matt, the trombone player, didn’t pursue a jazz career, but Sun Ra’s pull on him remains strong. He recently emailed from China, where he works in infotech but also still performs music, for fun: “Played a gig last night that had definite tones of Saturn.”

As for me, I don’t play Sun Ra’s music anymore—not even in an amateur group or by myself at home. In fact, I haven’t played my horn for more than thirty years. Its case, in my closet, gathers dust.

Three weeks after our Boston gig, Don announced distressing news: Sun Ra had had a stroke. The tour was off.

And that, as it turned out, was that.

Life went on. I finished my thesis and my other tasks. I performed with the Coast one last time—the Senior Show—and I was back to being nothing more than what I truly was: a decent dabbler in a solid college band.

Without Barbary Coast, my trumpet playing dwindled; it was hard to practice when I didn’t know what for. Eventually I moved to Boston, where my neighbors, I told myself, would have made a stink about the racket. True, I could have found a group to join, rented a practice space. Hell, I simply could have used a mute. Maybe the trumpet was something I just outgrew.

But all these years it’s irked me that I lost my drive to play the horn so soon after our near-miss with Sun Ra, that my brush with the big time led to…well, to quitting.

Led to. Why am I so tempted to draw a link?

The tour’s cancellation certainly sapped our spirit, but for me it also brought relief. As much as I’d longed for adventure in the abstract, I’d feared how the actual trip might go: the foreignness of the places, the people. Easier just to stay at school, enjoying all the parties.

Maybe I already knew what would make a better story: the whopper that got away. It’s a tale I’ve told and told again to scores of friends who didn’t even know I played the trumpet. Especially now, in middle age, I love dropping Sun Ra’s name. And yet the story rings a little false. I’ve billed it as a tale about coming this close to something, when really, I can see now, the lesson was how far away I always really was.

Recently, through the uncanny magic of the web, I found a bootleg recording of the Boston show; in no time, MP3 files landed in my Dropbox. (Imagine Sun Ra’s joy—his music beamed through space at the speed of light!)

For days, I couldn’t bring myself to listen. What if I’d actually flubbed my solo? What if my playing ruined the performance? But when I finally summoned the guts, what I heard was maybe more disturbing.

There are licks that sound like mine, and then another horn: Jothan, I figured, coming downstage to joust. But no—the second horn sounds even more like mine. Did Jothan go first, and then I joined? All these years, have I had it backwards? I’ve listened a dozen times, and I can’t tell. Maybe that seems a good thing: when it counted, my playing passed muster. But Jothan was a pro, a lifelong jazz master. Shouldn’t I be able to tell his solo from my own? Shouldn’t any listener hear the difference? The fact that I couldn’t distinguish his licks from mine typifies why jazz couldn’t have been the path for me.

Not that Sun Ra’s music wasn’t exacting. Often mislabeled “free,” his style required control: methodical open-mindedness, rigorous relaxation. And yet the music’s power, like that of all true jazz, depended on heart-not-head abandon. Which is how an amateur, clad in a borrowed toga, could feature in a concert as notably as a seasoned band member.

It was my own unlikely success that bothered me the most: if I was going to succeed at something, I wanted it to demand skills that couldn’t be pretended. As much as I might gripe about the grind of meritocracy, it turned out I couldn’t thrive without it. Sun Ra had believed—and made me, too, believe—that he’d awoken a cosmic spirit within me, but maybe what he’d triggered was my same-old striving self: follower of directions, teacher’s pet. Which meant I’d gotten his message exactly wrong. Conforming to someone else’s style: that’s what Sun Ra scorned.

But playing with him did help me nail down my own nature: I wanted to be spontaneous, but not that spontaneous; wanted a calling where ad-libbing didn’t count for quite so much. Better for me the nuts-and-bolts march toward expertise. Jazz had been an outlet when my life was full of strictures and I liked to think of myself as offbeat; now that I was starting the open solo of adulthood, I had to face the truth of my own music.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Place Envy: Essays in Search of Orientation by Michael Lowenthal. Published by Ohio State University Press. An earlier version of this essay appeared in Ploughshares. Copyright © 2026 by Michael Lowenthal. All rights reserved.

Michael Lowenthal

Michael Lowenthal is the author of the novels The Same Embrace, Avoidance, Charity Girl, and The Paternity Test and of the short story collection Sex with Strangers. His writing has appeared in Tin House, Ploughshares, The New York Times Magazine, The Boston Globe, The Washington Post, Out, and many other publications. His stories have been widely anthologized in such volumes as Lost Tribe: Jewish Fiction from the Edge, ,Bestial Noise: The Tin House Fiction Reader, and Best New American Voices.