What Our Continual Desire For Transformation Reveals About Ourselves

Oren Harman Explores the Philosophical and Literary Side of Metamorphosis

“How many creatures walking on this earth / Have their first being in another form?” the Roman poet Ovid asked two thousand years ago. He couldn’t have known the full extent of the truth. That creatures transform ran counter to Aristotelian science. It was considered a heresy by many even in Darwin’s day. Yet, from caterpillars turning into butterflies, elvers in eels, and sea sprigs into immortal jellyfish and back again in frigid water depths, the majority of animals radically transform in order to become who they are. According to current estimates, nearly three-quarters of all animal species on Earth undergo a form of metamorphosis.

Formally defined as “radical post-embryonic development”, metamorphosis is an amalgam of two Greek words meaning “transformation” or “transforming.” There is hope implied in this: a wormy caterpillar can turn one day into a flitting swallowtail, a modest nymph into a dragon-like salamander. But what about us? Do we stand a chance of transforming? Most people think of metamorphosis as related to creepy crawly things very much unlike us humans, to slippery and slimy creatures far removed from our mortal concerns. There’s truth to this: technically we’re not considered metamorphic creatures, which is maybe why we’ve invented superheroes to adore like Superman and the Transformers.

But when you think of it for a moment, the biological definition of metamorphosis is arbitrary: how “radical” does change have to be to be considered “metamorphic”, and who gets to decide? We humans may not turn from caterpillars into butterflies, but most of us would agree that we undergo pretty dramatic post-embryonic development. We have the US Supreme Court on our side. In the 2012 case of Miller v. Alabama, based among other things on amicus curiae by the American Medical Association and American Psychological Association showing that young people’s brains are wired differently than adults, the highest court in the land decided that adolescent murderers cannot be given life without parole. Creatures are said to be either metamorphic or not, but in reality they lay on a continuum. Having evolved from an ancient progenitor of jellyfish, in our own special way, we too metamorphose.

Metamorphosis in a more lyrical sense is a portal into our innermost obsession: why we yearn to transform but are also afraid of it.

There was little chance of us not noticing. Moons sliver, seeds sprout, empires rise and crumble. Everything in the world around us, including our bodies, is in flux. And yet as witnesses to change, we have been and remain ambivalent: we cheer the flowering bud but mourn the rotting fruit. We search for our younger selves in mirrors while praising the wisdom that comes with wrinkles. Carried by hopes and shackled by memories, we struggle to live in the moment. Perhaps this is why in so many cultures, we’ve imagined ourselves with the following metaphors: earth molded and remolded, flowing rivers, passing shadows, falling leaves.

As a cultural preoccupation metamorphosis has attracted the attention of artists from Orwell to Ovid, philosophers from Plato to Parfit, and followers of every god or son of god from Jupiter to Jesus to Jagannath. In modern times it’s spawned plays like Peter Pan, inspired music by Strauss and paintings by Dáli and Kafka’s Gregor Samsa, to name but a few. Perhaps that’s because alongside being a gateway into the biology of growth, metamorphosis in a more lyrical sense is a portal into our innermost obsession: why we yearn to transform but are also afraid of it. What it feels like to be ourselves. How it’s possible that we remain the same while changing all the while.

Over the centuries we’ve imagined metamorphosing creatures using three different orders—Philosophy, God, and Science. The ancient Greeks looked at a butterfly emerging from its chrysalis as proof of a causal Universe leading up to us; lowly insects and slimy frogs had to transform because they were born “imperfect,” unlike us humans. Medieval Christians looked at the very same phenomenon and imagined it as a reflection of divine will, the transformation of a wriggly worm into a flying jewel an earthly reminder of the transfiguration of Jesus to Christ. Today we think of metamorphosis as a scientific problem in genetics and physiology, a road taken, for reasons we are still trying to discern, on a blind evolutionary path.

Looking at the natural world, metamorphosis does seem so strange a phenomena, at once almost universal and very idiosyncratic. And yet the imprecision of definitions of metamorphosis throughout the ages, the degree to which the meaning of change is always in the eye of the beholder, make it clear just how intimately science and culture walk hand in hand. How we define metamorphosis is tied to our ever-changing views of our human selves.

In the end, we do science for practical reasons, like better medicines and weather forecasts and more efficient agriculture, and electronics. Often we do it to find “truth.” But we also engage in science to encounter metaphors that help explain life to us. And as creatures that grow, adapt and remember, metamorphosis is a puzzle that speaks to us in a very personal way. Sometimes, when we look at ourselves closely, we disband, like a caterpillar in a chrysalis. Just as often, when we look to our past, we say: “I was a different person then.”

But on most days we feel like ourselves, despite the fact that we’re constantly changing. And so it means something to us to learn that grown butterflies have memories from the time they were caterpillars. It means something that starfish can exist as two separate—juvenile and adult—selves. What identity is will probably forever remain a secret to us. But each of us, whether we’re doing science or making art or just waking up in the morning, will spend a lifetime trying to figure it out.

__________________________________

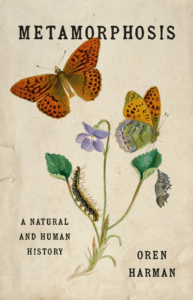

Metamorphosis: A Natural and Human History by Oren Harman is available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group.

Oren Harman

Oren Harman is Senior Research Fellow at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute and teaches at the Graduate Program in Science Technology and Society at Bar-Ilan University. His books include Evolutions and The Price of Altruism, which won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. He lives in Berlin and Jerusalem.