What My Grandmother’s Death Folder Taught Me About Love and Duty

Eden Royce on the Importance of Taking Care of Funerary Details in the Face of Grief

My grandmother showed me her death folder when I was eight years old.

She was a practical woman, born on a farm in upstate South Carolina, married to a Gullah man from Johns Island when she was barely an adult. She didn’t smile in her wedding picture and I used to wonder if that was because she didn’t want to be there or because that was the done thing back then. Seriousness about everything. Especially about anything lasting. Especially death.

It was a plain manila folder. I don’t know why I’d expected it to be spectacular. A blaze of flaming glory. But that wasn’t my grandmother’s style. Although she denied using rootwork and hoodoo, she saw things. “Just knew” even more. She said spectacular wasn’t the kind of death she was going to have and it wasn’t the kind she wanted either.

What she wanted was for me to pay attention to her wishes.

Laying someone to rest is the final act of care that leaves a lingering impression, not only on the dead, but on you.

On that day, with the window air conditioning unit droning on, she bent down to my height and looked me in the eye. “I’ma show you my death papers, yuh? I want to you remember where they are and what to do with ’em.” Behind her, the air conditioning lifted the sheer white curtains, making it look like she had wings.

People of her generation had a practicality born of necessity. She was the youngest child of seven, born to a Renaissance man father: pig farmer, tobacco harvester, and coffin maker. He had clients who came to him for all three. Death was a part of her life and my gramma had to learn to live with it.

She kept the death papers in a two-drawer filing cabinet in her bedroom.

Making these plans was one of the only ways she felt she could be really and truly heard. So many Black people of her generation (and of mine too, I suppose) were ignored, overlooked in life. Even now when I hear or read “Listen to Black women” I can’t help but think, yeah…right. No one listens to us.

Not no one. But few…too few.

Raising children with strict rules usually ensured they’d listen for a short time. By reading what was in that death folder, my eight-year-old self was making a promise that I would listen not only at this moment, but once she was gone, as well. That I would adhere to every request I could.

I promised, but only after I asked, why me?

It was a silly question. Why not? Because in my culture, it is the to-be-deceased’s choice. It shouldn’t matter why they chose you—they’d done so and it was an honor.

But gramma answered my question without blinking. “’Cause your mama… she won’t remember when the time comes. You know every inch of this house. And I know you’ll remember.”

Remembering can be a burden, just as final preparations for a loved one are a weight. That planning for the service is the last thing you will ever do for them while they are here on earth. And it is a huge event, spanning neighborhoods, cities, and states, usurping bad blood and family feuds, especially in the Black community. Especially in the Gullah community. Laying someone to rest is the final act of care that leaves a lingering impression, not only on the dead, but on you. It’s showing the respect we deserve as humans that the world at large does not always give our people in life. The time and reverence you show to Black bodies when so often the world has not.

The folder contained:

Several life insurance booklets, all from back in the day when insurance salesmen came to your house once a quarter to collect your insurance payment and give you a receipt for the cash. All those tiny, strips of paper turning yellow-brown tucked safely into the frayed-edge cardboard.

Another receipt, this one for the graveyard plots Gramma had bought for my grandfather and herself. Dated before I was born, the paper showed the plots were next to each other, and that grandad’s had been claimed.

A letter in her scratchy handwriting with where her plot was located, the insurance companies and the policy numbers in case things got separated. Policy certificates on each of her three children lay in the folder, for my mother and her two sisters, as well as one for me.

I’d thought planning was only for old people on the cusp of death. But without my knowledge, preparations had already been made for me. I’d been close to death once. (As a baby, I didn’t remember the details.) When I touched the policy book, it was stiff, textured like an invitation to a fancy party I wanted to keep.

In the drawer of our china cabinet was a stack of funeral programs. That same drawer also held a recorder in a burgundy leather pouch and a set of extension cords in varying lengths. Once, I’d snuck a long gray cord outside to jump rope with. Gramma saw me and shouted for me to return it to the drawer. When I did, I asked, who are all these dead people? Why do you keep them?

I don’t never throw the dead away, she’d said.

Decades later, I saw the death folder again. I was living in Charlotte, NC when I got the call gramma had died. I told my boss what happened and she’d said, “Go.”

I was in full task mode, like a sleeper cell that had been activated. All I could think was: Get the file. I went to my townhouse, packed a bag, then drove the three hours home. I plucked the death folder from its drawer and sat on the sofa with it next to me while my old laptop burned my thighs through my khaki pants. My mother sat at the dining room table, smiling as she thumbed through old pictures in a shoebox.

Cause your mama… she won’t remember when the time comes.

I called the funeral home, the insurance companies, the newspaper, family I knew, and family friends I didn’t. My mouth was dry from talking. I hadn’t slept. My fingers hurt from typing out the funeral program, the obituaries and death announcements for the white newspaper and the Black one. Writing and rewriting. To this day it is the hardest editing job I’ve ever done.

When the insurance companies asked for policy numbers, I had them. There was a lot of, “Oh, that’s an old one…” Belatedly, I realized all her planning had not been for her, but for me. She’d wanted to make it easier for me to give her this send-off.

Knowing she’d trusted me from the age of eight to handle her final affairs was a blessing I didn’t realize would take me through some of the hardest decisions I’d ever have to make.

I chose her undergarments, her clothing, and shoes. I had a consultation with the mortician about her makeup. He showed me the products he thought would work best. To my surprise, he held up a bottle of the same brand and shade of foundation I was using at the time. There was some synchronicity in that occurrence I’m sure I appreciated at the moment.

Aside from my extreme fatigue, and a hiccup over the burial plot that was soon resolved, the services happened as they should have. My grandmother and her death folder had seen to that. On the day of the wake, the house was full of people. Some I knew, many I didn’t. They were everywhere: the dining room, the living room, the kitchen, the hallway. An introvert to my core, I snuck off to my grandmother’s bedroom and lay down on the bed.

My mother came in soon after.

Aren’t you scared to stay in here by yourself?

No, I sighed, dragging the fading scent of liniment and orange peel into my lungs. Gramma loved me when she was alive. That’s not going to change now.

Mama nodded and gently closed the door.

Knowing she’d trusted me from the age of eight to handle her final affairs was a blessing I didn’t realize would take me through some of the hardest decisions I’d ever have to make.

Three years later, I moved. When looking through a box of paperwork, I found a sympathy card a friend gave me at my gramma’s funeral. I read it and for the first time, I broke down. I let myself have the moments of grieving I’d denied myself in order to give her the homegoing she wanted. I ugly cried like a child until I was empty.

Recently, I was looking for a short story I’d begun but set aside. I couldn’t recall what I’d titled it, so I searched my computer docs for the word “funeral.” More than ten stories appeared in the search listing. I hadn’t realized that funerals were such a huge part of my writing themes.

It would be another ten years before I felt ready to tackle a longer work based on those experiences of laying my grandmother to rest. When I mentioned the idea to my first literary agent, she wasn’t sold on the concept. Isn’t there some other motivation you can give your protagonist for going to another city to plan a funeral? Some other plot point? Another reason?

“No,” I said. “That’s all.” Love, duty, and the death folder. Not a bad title, if you ask me.

__________________________________

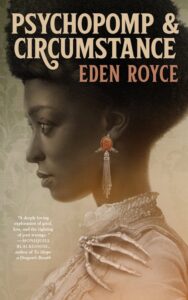

Psychopomp & Circumstance by Eden Royce is available from Tordotcom.

Eden Royce

Eden Royce is a writer from Charleston, South Carolina now living in Southeast England. She is a Shirley Jackson Award finalist for her adult short fiction, which has appeared in various print and online magazines. Her debut middle grade novel, Root Magic is a Walter Award Honoree, a Nebula Award finalist, a Mythopoeic Fantasy Award winner, and an Ignyte award winner for outstanding children’s literature.