What My Grandfather Saw Photographing the 1919 Typhus Epidemic in Poland

Joe T. Marshall Went From Harvard to the Red Cross

I never saw my paternal grandfather, Joe T. Marshall, hold a camera. It was my mother’s father, Fred Spiess, the son of a German immigrant baker in New York City who’d run away at 15 to California, who recorded family outings in Kodak snapshots and Super 8, returned from vacations and business trips to Europe and “the Orient” with packed slide carousels, and bored us silly in two mediums with his after-dinner screenings.

Joe Marshall was a different sort of runaway—a Harvard man, class of 1913, the son of Kansas cornfield wealth. Although the family fortune dwindled even before the Depression, Marshall money carried Joe from Concordia to Cambridge, and then on a grand tour of Japan, the Philippines, India, and Egypt before he settled in Paris for nearly a year of intensive language study after the outbreak of the Great War.

As a Harvard senior, Joe had heard the Bengali Nobelist Rabindrinath Tagore deliver six lectures on “Indian Philosophy in Its Application to Life,” and was inspired to scrap his plans for law school in favor of world travel. In August 1914 he wangled an interview, becoming the first American to present himself at Tagore’s ashram, Santiniketan, “the abode of peace.” That same week Germany invaded Belgium, ending the “Long Peace” that had held for a century in Europe and provoking France and England to declare war in response.

Joe T. Marshall (standing, farthest right) with members of the 1919 Red Cross Inter-Allied Medical Commission, sent to investigate the typhus situation in Poland, and officers of the Polish Army, Poland, 1919. All photos courtesy of Harvard University Archives.

Joe T. Marshall (standing, farthest right) with members of the 1919 Red Cross Inter-Allied Medical Commission, sent to investigate the typhus situation in Poland, and officers of the Polish Army, Poland, 1919. All photos courtesy of Harvard University Archives.

The immediate consequence for Joe was the cancellation of his passage to Egypt on a German steamer no longer welcome in the British-Indian port of Calcutta. There would be greater disruptions to come. “Europe is as the setting sun,” Tagore warned as they parted. “It has risen in its greatness and power by unnatural means; and as the sun sinks in a flood of red light, so Europe will sink in a flood of red blood.”

Joe died in 1974, at 85, when I was 20. I’d grown up five miles from my grandparents’ Altadena bungalow, but for many of those years he was descending into senility. A tall, formal gentleman, always dressed in gray wool trousers and a button-up sweater in my memory, he seemed a relic of the past. What I knew of his life was related by my father and grandmother; and there hadn’t been much to say, embarrassed as they appeared to be by our patriarch’s mental decline, a subject that was not discussed.

Joe Marshall’s papers reached me decades later at my home on the opposite coast, and I donated them to Harvard University Archives where, during the summer of 2018, I finally made time to read them.

*

Joe wrote countless letters home to his mother—Phenie, short for Josephine—on whom, I quickly gleaned, he relied for advice. “It is my ambition to have you speak more than one foreign language fluently, so that no matter what turn the Wheel takes it will find you capable of catching hold,” she’d written in July 1914, encouraging him to stick to his plan of study in Europe even as war threatened. I’d expected letters. But in amongst the handwritten pages I began to find photographs, quite evidently the work of my grandfather.

Josef Kwieciński, a fifteen-year-old Polish Army volunteer.

Josef Kwieciński, a fifteen-year-old Polish Army volunteer.

The earliest was a selfie taken in his Harvard dorm. Joe had been pleased with the results, he wrote to Phenie, achieved by “flashlight”:the portrait of a young man in pressed wool slacks and dressing gown, lounging a bit stiffly on the window seat with book in hand, typewriter at the ready, and a plaque above the door listing the room’s previous residents of note: Andrew Preston Peabody, ’26; Henry David Thoreau, ’37. But few of the other photos featured Joe.

No “flashlight” could have helped Joe capture the sweeping nightscapes of aerial warfare he witnessed in Paris during his 1915 year of study.

His aim was to document the places he visited and people he met: families in front of tile- or thatch-roofed dwellings; crowded river boats; a party of well-dressed Americans with whom he traveled on horseback into Luzon, a territory of the Philippines that had “never before been visited by a white man.” Joe hated “cold-blooded sight-seeing,” and tried his best to travel “understandingly,” he wrote home to Phenie. “I call myself ‘student’ rather than ‘tourist.’”

The photos were remarkable simply for their existence, the recordthey bore of unique interactions, of the wonder felt by a 24-year-old fresh from the warm embrace of Harvard and its Glee Club, who sang “The Road to Mandalay” and “Invictus” in the living rooms of the well-to-do hosts he’d met traveling first class, accompanying himself on the piano. Who carried folded in his wallet quotations from Teddy Roosevelt’s The Strenuous Life and Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, along with lines jotted down during one of Tagore’s Harvard lectures: “Love is not mere sentiment; it is truth; it is the joy which is the foundation of creation.” Whose mother sent him a news clipping advising, “The world belongs to him who has seen it.”

A marketplace at Dubno.

A marketplace at Dubno.

And then, as I paged through the letters describing wartime Paris and Joe’s regimen of classes in the spring and summer of 1915, there were no more. Not until a handful of images dated 1918, and an intriguing box filled with what appeared to be snapshots from the waning summer weeks of 1919.

*

No “flashlight” could have helped Joe capture the sweeping nightscapes of aerial warfare he witnessed in Paris during his 1915 year of study, though he wrote home of one dark night when he stood with a crowd of neighbors on a street corner and watched as two German Zeppelins dropped “about 40 bombs” on the city’s outskirts, a sight that to him seemed almost beautiful: “the ghostly looking Zeppelins, the noise of the cannons, the bursting shells, the graceful flight of the airplanes, and the searchlights flashing all around.” He ended his studies soon after and returned home determined finally to “take a fall out of the future”: to grow up.

Persuaded of the view held “unanimously” by the American colony in Paris that his country should join the Allies, Joe organized a series of recitals across Kansas to benefit Belgian orphans and bided his time until President Wilson finally asked Congress to declare war in April 1917. By June, he was back in Paris with his new bride, Elizabeth Metcalf, ready to be sworn in as a second lieutenant in the Army Press Corps.

The youngest officer on the team, Joe was given charge of photography and film. For the next 18 months he escorted press and Army photographers to the front, edited their film, wrote press releases, and distributed still photos and newsreels around the world, showing America’s part in the war to best advantage.

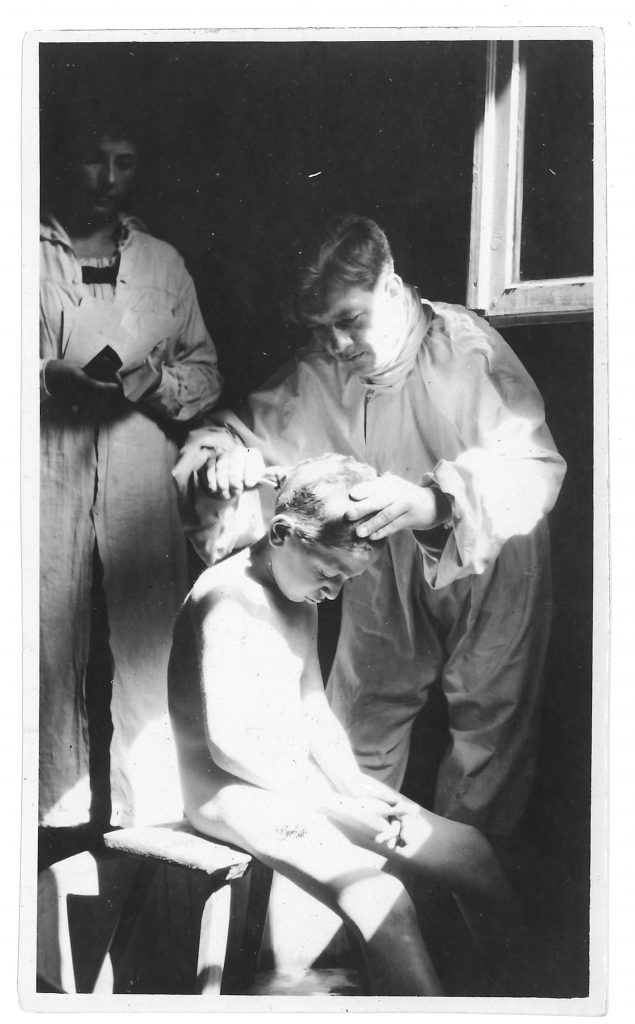

Clipping hair of a boy infested with lice at a bathing station in Warsaw.

Clipping hair of a boy infested with lice at a bathing station in Warsaw.

Joe’s few personal photos from 1918 record the young life of my grandparents’ first child, born in Paris nine months after their wedding night. These are artfully posed and lit: my grandmother settled on the grass of the Bois de Boulogne in a pool of white skirts, beaming as she holds up curly-haired little Joe Jr.; mother and son seated in a plush armchair in a darkened room, a shaft of light illuminating the two as they study a book, a single rose in a small vase on the table beside them.

These photos don’t reveal, indeed may have been intended to conceal, how the war had frayed the young couple’s nerves. Elizabeth’s breast milk failed as “la Grosse Bertha” and fleets of Gotha bombers blasted away through the night in a fierce German assault on Paris. Joe Sr. caught the Spanish Flu, lost weight, and was forced to take a medicalleave, joining his wife and son at their summer refuge on the Brittany coast for several weeks in July 1918 before returning to work as the tide of the war shifted toward an Allied victory.

Joe’s commanding officers in the Press Corps had fared worse—five in a row stepped down due to “exhaustion, nervous breakdowns, or illness,” he wrote to Phenie. In a global conflict that ultimately cost the lives of over one-hundred thousand American troops and more than nine million soldiers of all nationalities, putting a good face on things was not “an easy sort of work.” Nor was the job he took after the Armistice was signed in November 1918.

Joe was offered a position as “publicity man” for the newly formed League of Red Cross Societies, the first-ever international relief organization, chartered in tandem with the League of Nations. It was “the greatest opportunity for service that has ever come my way,” he explained to Phenie in a letter announcing his decision to remain overseas. Joe and Elizabeth, who’d experienced their first years of independence in Paris, wanted to stay on and savor the peace.

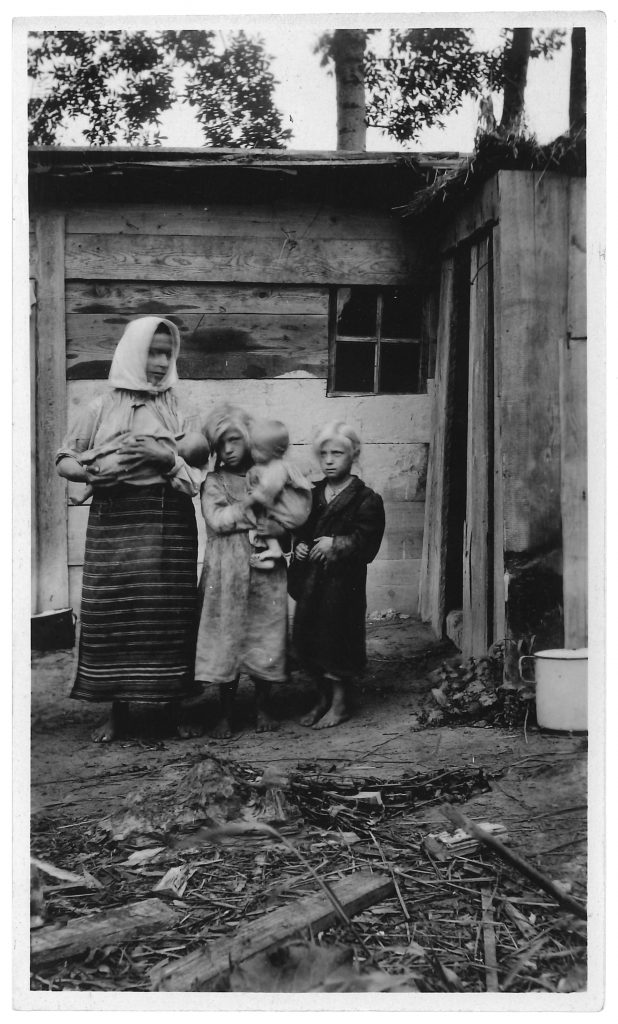

Destitute family in the village of Suchodoly, near Brody. Their house was destroyed by artillery fire and they are living in a hutconstructed on the ruins of their former home.

Destitute family in the village of Suchodoly, near Brody. Their house was destroyed by artillery fire and they are living in a hutconstructed on the ruins of their former home.

But Joe’s long hours cut into their pleasures, while rumors of severe winter food and coal shortages, as well as a threatened general strike, dimmed their prospects. They booked passage home in October 1919, and Joe fulfilled a last assignment, joining eight League representatives on a fact-finding mission to the newly founded Second Polish Republic, still under threat from Germany and engaged in the early skirmishes of a border war with Bolshevik Russia.

A typhus epidemic had overtaken southeastern Poland, a territory of farm villages and industrial towns ravaged by the recent war, endangering the rest of Europe if the disease, borne by lice in squalid conditions, was not contained. Joe, now 29 and still the youngest man on a team of high-ranking medical officers from Italy, France, England, and the United States, would document the Inter-Allied Medical Commission’s findings as writer and photographer.

*

Joe’s journal of August 17th to September 7th, 1919, recording the journey by train and military convoy through the former Kingdom of Galicia, a province of the new Poland, makes no mention of his role as photog- rapher. The only proof I have that he made the nearly 100 images is the parenthetical line of credit on a typewritten list of captions composed on his return: “(série 1–72 taken by Joe T. Marshall).”

These were the faces of refugees, prisoners of war, stricken villagers anywhere. Any time. Now. And Joe had rendered them beautiful, sad, affecting.

In the small white archival box at HUA that holds the stack of 3×5 black-and- white prints, I found two dozen more similar snapshots, not listed in Joe’s inventory, with “Marshall” penciled on the back. Many of these images are so sharp, so arresting, that I assumed, until I read Joe’s terse self-attribution, they’d been taken by a professional.

There are occasional signs of amateurishness or inattention—a boy soldier, identified as “young Polish volunteer of 15 years,” is cut off at the toes. A few of the outdoor scenes are overexposed. But a remarkable number of the images transcend the basic charge to document the team’s activities and findings. Or was it the interval of a century between Joe’s moment and mine that made me catch my breath, apprehending not only the urgency that Joe and his team wished to convey but also a timelessness? These were the faces of refugees, prisoners of war, stricken villagers anywhere. Any time. Now. And Joe had rendered them beautiful, sad, affecting—works of art.

A handful of Joe’s photos were reproduced in the League’s bulletins to illustrate a report he titled “Convalescent Poland.” Fourteen were made into glass lantern slides for use in lectures. But I turned to Joe’s handwritten journal to recover what he might have been feeling as he took the pictures.

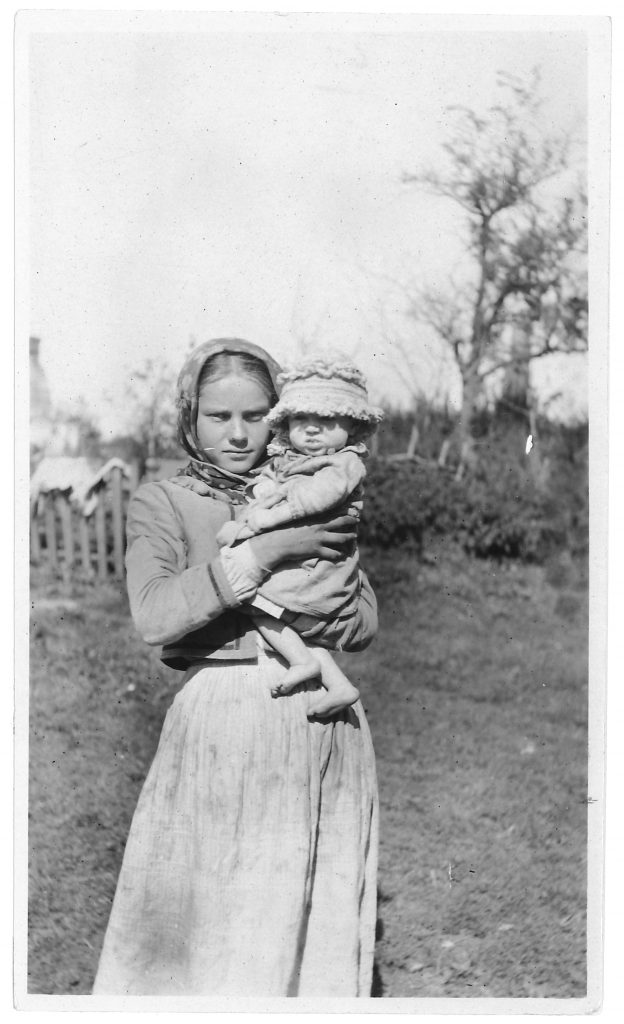

Young woman and child in the village of Sokolniki.

Young woman and child in the village of Sokolniki.

Each day was a new city, town, or village, and Joe’s entries opened with population figures. The cities had expanded—Lublin from 60,000 to 105,000; Cracow 180,00 to 240,000—as refugees arrived from the countryside seeking assistance or returned from camps in Russia to find their homes destroyed. Smaller towns had dwindled—Brody droppedfrom 20,000 to 11,000; Kowel from 30,000 to 24,000. In Kowel and its surrounding district, one quarter of the population had died of typhus: “Entire villages wiped out.”

Two-thirds of those living outside the city on farmland riven with abandoned trenches and laced with barbed wire had succumbed to “famine, typhus, etc.” The U.S. foreign minister, with whom the commissioners had conferred in Warsaw before venturing into the countryside, had warned that “Belgium is a paradise compared to Poland.” They would find “human sparrows living on grass, bark, and nettle soup.”

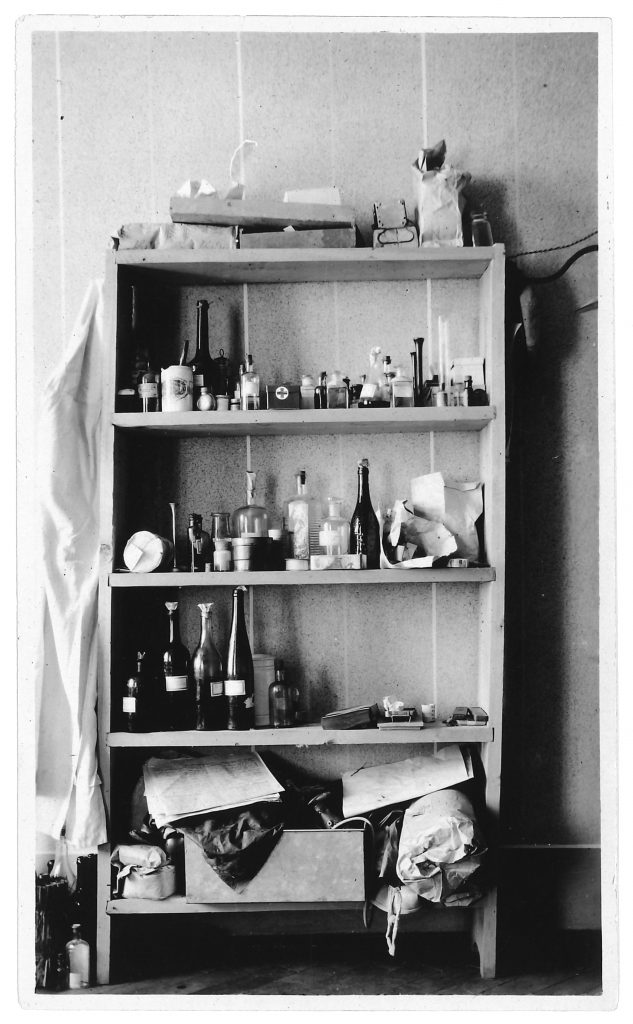

From demographics Joe proceeded to inventory doctors and hospital supplies. Kowel: “14 doctors in the city for 24,000, 2 doctors in district for 200,000.” “All blankets requisitioned by the Russians and Austrians.” Lublin: “Hospitals lack everything. No linens, blankets, nor dressings…insufficient quantities of drugs and supplies.” Chelm: “a ho pital with 200 beds… only 160 sheets.” Tarnopol: “No mattresses.”

The commission visited “disinfection stations” where refugees could bathe and get their clothes washed, their hair checked for lice. But with no fresh clothing on offer and never enough soap, the situation was dire. “Many people living underground,” Joe noted in Lublin. “Many rats,” another vector of transmission. In Brody: “People living in dugouts—hell when it rains.”

Several entries closed with a quick sketch of his surroundings: “Big bare room—long oilcloth-covered table—many flies and mosquitoes— haggard officials—tired eyes—coarse clothes.” Or: “Refugee camp toward evening enceinte woman pleading for food and clothing or permission to leave—camp fires—gorgeous sunset—quiet voiced pleading women.” These scenes, which didn’t make it into Joe’s report, brought his days to life, as the photographs had.

Entire stock of medical supplies of a 300-bed hospital at Czortkow.

Entire stock of medical supplies of a 300-bed hospital at Czortkow.

In Kopyczuce, near the end of the tour, Joe lost patience, in his diary at least. The hospital’s chief surgeon and half the hospital staff were sick with typhoid, transmitted through contaminated water: “Wellsdrain directly back into the well—why can’t people see it?” Joe had been looking closely, taking notes, aiming his camera. He couldn’t see how others might be blindered by circumstance: fear, fatigue, hunger, the confusion of ceaseless regime change. Joe’s entry on the day the team arrived in Lwów reads like a macabre nursery rhyme:

Taken by Russians Sept. 1914

Retaken by Austrians June 1, 1915

Taken by Ukrainians Nov. 1, 1918

Taken by Poles (students) Nov. 15, 1918

Besieged for 6 months longer

Photographing postwar Paris this same year and after, Eugène Atget selected as subjects buildings and streets that were slated for demolition.“Va disparaître” (will disappear), he wrote on the back of his prints. His studio advertised “Documents pourartistes.” Workingin a time before photography was widely recognized as an art, Atget imagined the artists of Paris might use his “documents” as points of reference for their own creations.

Joe’s photos, disappeared for so long, were also meant to serve as documents. Although they don’t rise to the level of Atget’s achievement, they accomplish more than their photographer’s stated intention, perhaps something closer to the effects of biography: the resurrection of past lives.

__________________________________

Originally published in Harvard Review 55. Reprinted courtesy of Harvard Review, Houghton Library, Harvard University. https://www.harvardreview.org/print-issue/harvard-review-55/

Megan Marshall

Megan Marshall is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Margaret Fuller: A New American Life, Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast, and The Peabody Sisters, a Pulitzer Prize finalist. Her most recent book is the essay collection, After Lives: On Biography and the Mysteries of the Human Heart.