The list of words coopted by business grows all the time. I was thinking how much has changed for those who study or hail from the Amazon, or are named Alexa. As critics have pointed out, even a novel as early as Robinson Crusoe is infused with an everyday language of capital. We can’t get away from it. Time is spent. Attention is paid. Some conclusions we don’t buy. The urge of so many where art is concerned—mine too—is to defend a wall between its making—the fewer commercial concerns the better—and its dissemination, where the methods of business can widen the circle.

But a literary culture suffers, I think, if it avoids talking about value. Business and capital may define the word in exclusively financial terms, but in the land beyond, value remains an important dimension of meaning—it’s part of the why, and gives a different weight to the question “What is it worth?”

*

Submissions got me on this subject: I’m coeditor of AGNI, and in recent years we’ve received a lot of direct homages and close imitations. These aren’t mere borrowings of structure or repurposings of plot, which can serve any conceivable end, but ventriloquisms—clonings of another writer’s tics of language and gesture. The results can be bogglingly good. Along comes Philip Larkin, along comes Thomas Bernhard, Adrienne Rich, Chinua Achebe.

I’ve co-taught with a friend who assigns an imitation exercise, and I’m stunned every time to see how students who have yet to trust or recognize their own innate sense of form and sound will reveal a clear instinct for the tonal registers of diction, the pacing afforded by syntax, as soon as the vine of their thoughts has a trellis to cling to.

But when that kind of writing is sent as finished work—it’s an impulse familiar to me: one of my own short stories amounts to that kind of mimicry—the copy revives questions, as any good forgery will, about what confers or constitutes value.

*

When someone talks about a “good writer,” the phrase suggests a way with words, an ear for rhythm, maybe even a structural vision. But often the phrase means more than that: the reader is compelled by the associative connections made; the landscape of the characters’ or speakers’ reactions, especially to people; the generosity or resistance suggested by a way with humor; the languor, rigor, focus, or musicality implied by the habit of flow, how stanzas, scenes, paragraphs move one to the next; and, bound up with all of that, the distinctiveness of the author’s seeing. They’re drawn to the cast of mind that reaches the page, something the writer has found within and learned to channel like a medium bringing spirits into the room.

*

In a writer’s apprenticeship, imitations are expressly designed to suspend: to remove the infinity of the blank page and allow focused practice by limiting the range to one set of moves, one predetermined stance. Sound this certain way, create that particular effect. As when translating, we have to choose—will we carry over the rhythm, the tone, the emotional pitch, the degree of immediacy, the literal meaning? Only the original can have it all.

Beauty in writing—whether rough and terrible; sad and groping; slow and intimate—relies on the presence, deep in the grain, of us.

What’s borrowed during these exercises is an abstract framework—a matter of focus, shading, atmosphere, certain details of technique; a flavor. But in the source, that framework, however conscious and intentional it becomes, rises in part from the accident of self. It reflects a warp in the writer’s lens, to use a Zadie Smith metaphor.

“Style is what happens,” Rick Moody once told his students, “when you strip away all affectation and realize you’re still eccentric.”

To extend his terms: homage is the donning of an affectation which in the original is not affect but essence.

After a time, the possibilities of imitation and affect expire. Fun with dress-up gives way to the more electric work of figuring out how to be true to yourself, and what yourself even is.

*

As we write what no one has yet written—including, by the way, our imitations—we make use, wittingly and unwittingly, in every smallest gesture, of our forebears’ and even our own past tools. We can anxiously try to recombine them, to “be original,” but the techniques available to us are handed down, above all through languages themselves and the limitations they impose. Writing relies on borrowings at every level.

Except one. And this is the thing that editors cannot insert into a piece of writing, but have to find already there. They—we—can work to remove the burr around it, bring it forward, make it more visible. But we only know it if we see it. And where it’s missing, there’s nothing that can’t be found with more life and greater energy somewhere else.

The discoveries that every writer can hope to arrive at, which can’t possibly be reached by any other, are mappings of any part of the known or imagined world as it appears to their own alien self. In other words, an arrival on the page—through focused attention on “as I alone see it,” “as it looks to me,” “as I’m compelled to construct it”—of the contours of their world, a world refracted through an inner quirk so obvious to the bearer that it can be hard to notice and then choose to value and preserve.

In his collection Black Paper, Teju Cole writes about the importance for him of the Italian painter Caravaggio. He says the work’s “mesmerizing power” has increased for him over the years. “And it cannot only be because of [Caravaggio’s] technical excellence. The paintings are often flawed, with problems of composition and foreshortening. My guess is that it has to do with how he put more of himself, more of his feelings, into paintings than anyone else had before him.” We can recognize the atmosphere of self. We’re trapped in one. To be able to immerse in another refreshes and broadens us; as Cole says, it’s mesmerizing.

*

Every narrative, even where a writer strives to see from a character’s or speaker’s point of view, carries something antecedent to perspective. It has to be one of the strangest features of both life and writing. We can spend ages trying to “find ourselves,” trying to catch up to the ever-changing gyrations inside; to understand. But from a close friend’s or deep reader’s vantage, the trace of a recognizable sensibility is rarely obscured. It emerges from a particular way with, or style of, inclusion and omission—a practically unbounded universe of words and details, but a person’s own universe, with its specifics of behavior, choice, observation, and language, what in daily life we might think of as personality.

A writer, journeying, arrives repeatedly at themselves, but not necessarily by looking inward; instead, by looking at—or for—their “material,” hewing to what activates them, and working through and past cliché to a rawer truth, past the received phrasings and reactions that we all carry inside us to a piece of writing that’s profoundly personal, no matter the subject, theme, or genre.

*

Sensibility. That’s the word that feels most accurate to me for the “personality” of a writer’s collected work. But to the degree that it hints at a stable, unified source, it’s probably misleading.

There was a profoundly upending time in my personal life when it didn’t seem to matter what I decided or thought—what I thought I thought. I always did what I was on the path to doing, what “I,” very clearly, “wanted.” Inwardly rejecting that route had no effect in the physical world of behavior. And as Stanislavski said, “Behavior is character.” Nothing happens unless it happens. We aren’t what we don’t do, no matter how important the refusals and resistances, the myriad limitations we set.

Around that time—a reading life is uncanny this way—I was in the middle of Antonio Tabucchi’s Pereira Declares and came across this description of an eighteenth-century “theory of the confederation of souls”:

It means that to believe in a “self ” as a distinct entity, quite distinct from the infinite variety of all the other “selves” that we have within us, is a fallacy. . . . What we think of as ourselves, our inward being, is only an effect, not a cause, and what’s more it is subject to the control of a ruling ego which has imposed its will on the confederation of our souls, so in the case of another ego arising, one stronger and more powerful, this ego overthrows the first ruling ego, takes its place and acquires the chieftainship of the cohort of souls, or rather the confederation, and remains in power until it is in turn overthrown by yet another ruling ego . . . [emphasis mine].

Tabucchi and his psychologist character make the “cohort of souls” sound like a back-stabbing Roman Senate. But the underlying metaphor—distinct selves within us, and rare occasions when one cedes dominance to another—illuminated a shift in me.

Imaginative writing—the real deal—is a high-stakes enterprise, even at its calmest.

Not long afterward, I read about epilepsy patients who’d had their corpus callosums cut, the bundle of nerves that allows communication between the two halves of the brain. The procedure is meant to reduce the frequency and severity of seizures, but in some patients, it can also expose a highly developed split in preferences and desires—a woman who says she loves smoking lights up with her right hand while her left, guided by the other lobe, consistently knocks away cigarettes, and only cigarettes. This too made sense to me. We aren’t so simple.

*

In college and for years afterward, I would sometimes sit with a notebook and try to write beautiful sentences. Try to write “well,” to fashion lovely prose about the things around me, abstracting them into marble tableaux. What I didn’t understand then was how beauty in writing—whether rough and terrible; sad and groping; slow and intimate—relies on the presence, deep in the grain, of us. It is nearly impossible to create more than an empty shell, like dried flowers, if the reactiveness, the caring of the writer, is scrubbed away or never brought to bear.

There are “no ideas but in things,” William Carlos Williams wrote. But there’s also no caring about things until they rub up against the human. This can mean having to excavate them from layers of tired meaning, to be able to then touch them in their actual relationship to oneself.

*

Imaginative writing—the real deal—is a high-stakes enterprise, even at its calmest. It has to matter for the writer, deeply, or the words flatten and die. A poet-friend calls it “writing painted with a self.”

The democratizing beauty here is that we all carry this value inside us. Value becomes a measure of our ability to access our own truth, and deep reading becomes the skill of hearing the true notes that rise up from another person’s thoughtscape. For writers, mentorship can emphasize this spelunking as the goal. That can make all the difference. But exploration, especially when carried out through the indirect means that are the essence of imaginative writing, cannot be taught or even insisted on.

That the writer’s self must be profoundly engaged for the work to succeed—this seems to find expression in classrooms only rarely. Many teachers do hint at it, expecting, as my partner puts it, “not just that it coheres, but that it coheres into something meaningful, worthwhile.” And in that advice a philosophy is embedded: that unless the writer cares, the reader can’t; that a sense of need—at the magazine we use the word urgency—is so essential to the creation of the most compelling work that great writing, by definition, holds value within it, the way skyscrapers inevitably contain steel.

This kind of writing accomplishes a rare, necessary thing: it conveys—intimately, between two thinking minds—a nuanced mapping of how the writer constructs worth. This would be tautological, and might open us to being deceived, except that when you encounter lines that stir you to bursting—different ones for different readers, because our receptors, too, have a shape—you then recognize the kind of transmission you’re receiving. You feel the arrival, and can choose to open yourself to it.

__________________________________

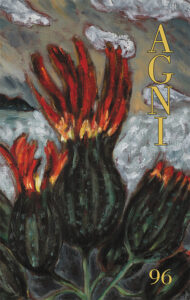

Place and displacement in AGNI’sfiftieth-anniversary issue, #96. Essayists Eileen Myles and Jessie van Eerden give visions of terra firma, exploring the space between fixity and mutability, while Teju Cole’s flash stories sketch liminal scenarios that locate the ways mystery attends us. Fiction by Emmelie Prophète (in Aidan Rooney’s translation) and an essay by Sofia Oumhani Benbahmed use settings of conflict and crisis to support a vexing search for identity; poets Michael Torres, Preeti Kaur Rajpal, and Diane Seuss return to moments that promise yet challenge belonging. Then founding editor Askold Melnyczuk and coeditor Sven Birkerts look back on 50 years of AGNI—from conception to full maturity. For a unique and celebratory art feature, we invited inspirations from a roster of former portfolio artists. Their theme: agni, which is to say, fire. The principle of combustion.” (Cover art: Anne Neely)

William Pierce

William Pierce is co-editor of AGNI. He is the author of Reality Hunger: On Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle (Arrowsmith Press, 2016), a monograph first serialized as a three-part essay at The Los Angeles Review of Books. His fiction has appeared in Granta, Ecotone, American Literary Review, and elsewhere, and other work has appeared in Electric Literature, Little Star, Tin House online, The Writer’s Chronicle, Solstice, Glimmer Train, Consequence, and as part of MacArthur Fellow Anna Schuleit Haber’s summer 2015 art project “The Alphabet,” commissioned by the Fitchburg Art Museum. With E. C. Osondu, he coedited The AGNI Portfolio of African Fiction.