What Jane Austen’s Possessions Reveal About Her Literary Ethos

Kathryn Sutherland Explores the Iconic Author’s Life and Work Through the Most Seemingly Mundane Objects

Small things can be almost sacred, as is Fanny Price’s “nest of comforts,” assembled out of bits and pieces in the old schoolroom at Mansfield Park—a faded footstool, a collection of family silhouettes, a sketch of her brother’s ship; objects none of which is considered good enough for display elsewhere. Or they can be slippery, unnoticed clues—in Emma, the spectacles whose loose rivet Frank Churchill is discovered mending with such fixed concentration in Miss Bates’s sitting room. The silver knife, relic of little dead Mary, over which Fanny’s sisters quarrel, is a disturbing accessory amid Portsmouth’s squalor.

Though, like Fanny’s amber cross, it possibly derives from something actual, an object Austen too may have lingered over: “has she a silver knife,” she enquires of Cassandra, June 30, 1808, anxious to provide an appropriate gift. In Persuasion, caught out by rain when walking in Bath, the comparative thickness of Anne Elliot’s boots is a topic to be dwelt on; Lady Russell staring through the carriage window is discovered to be watching out for a particular pair of curtains in a house across the road and not, as Anne supposes, for a glimpse of Captain Wentworth; during the musical evening in the Upper Assembly Rooms, Anne and Mr. Elliot hold between them a concert program from which she explains the words of an Italian song. Hardy concluded from such stubborn materiality that “things take a hand in human destiny,” and that though she resists “symbolic manipulation of things,” “the intimate connection of things with their owners and donors is more personal in Jane Austen than in any other novelist before her, and perhaps after her too.”

There is, also, something compensatory in a regard for faded footstools, thick boots and window curtains. Mundane objects link Austen the novelist to the letter writer whose fixing upon “little matters,” as she describes them to Cassandra, April 18, 1811, turns the emptiness of the female day—having nothing significant to say (a common refrain in her letters of obligation)—into fruitful watchfulness and a kind of redemption through random detail: “not being overburdened with subject—(having nothing at all to say)—I shall have no check to my Genius from beginning to end,” she wrote January 21, 1801. Accordingly, “I am still a Cat if I see a Mouse.” A woman’s letters, literally, are spaces to be filled, like household cupboards or drawers, and nothing that furnishes this end is wasted: “You know how interesting the purchase of a sponge-cake is to me.” The disconnected “nothings” of Austen’s domestic correspondence can take on the appearance of an inventory of the day’s passing moments. The domestic letter was her model for fiction, the shadow life of her novels. In her hands, the transfiguring challenge of the realist novel begins with the domestic letter: how and what do you write when you have so little to say?

*

Portrait of Jane Austen, c. 1810

Jane Austen is a tease. Her life coincided with the rise of a mass readership and a celebrity culture for the first time promoting women writers. Yet, in an age when even modest gentry families commissioned portrait miniatures and traveling painters were common, she, a writer with a growing lifetime reputation, has left no professional image. Her female contemporaries, Mary Wollstonecraft, Catharine Macaulay, Frances Burney, Amelia Opie, Mary Shelley, Hannah More, Sarah Trimmer, all have splendid public portraits in oils, the work of professional painters, hanging in the National Portrait Gallery (NPG), London. The only image from life to capture Austen’s face is this sketch made by her sister Cassandra, an averagely talented amateur. In the room where it now hangs, it is dwarfed by the grand likenesses of male Romantic poets with which it shares wall space.

A woman’s letters, literally, are spaces to be filled, like household cupboards or drawers, and nothing that furnishes this end is wasted.

Cassandra’s half-length sketch shows Jane, aged about thirty-five, at the beginning of her most intense period of novel writing: portrait of the artist as a middle-aged woman, perhaps? The image is lightly executed: there is no background; the dress, arms and hands are minimally, even clumsily, drawn. The eye is attracted to the only area of detail and finish: the face. In giving it definition Cassandra has used watercolor: warm brown for the hair, pale pink for the cheeks, mixed to a darker color to indicate shadows. She has taken pains to capture something particular in the expression. For the rest, the sketch appears unfinished. Was it abandoned out of a sense of failure or is the lack of finish part of its finished effect? The unfinished portrait drawing was a Regency fashion, as executed by professional society artists Thomas Lawrence and Richard Cosway, where the intention was to capture personality unawares, unstudied, as in life.

Austen’s image expresses energy at odds with its unformed context. How do we read the unsmiling face with its compressed, downturned mouth? Is it defiant? Scornful? Proud? Or simply guarded? What is the correspondence between a portrait and its subject? Is it a copy or an allusion? The NPG is cautious: “This frank sketch by her sister and closest confidante Cassandra is the only reasonably certain portrait from life to show Austen’s face.” In 1932 the Austen scholar R.W. Chapman, answering an enquiry from Sir Henry Hake, director of the NPG, described “a horrid little sketch (head) by Cassandra reproduced somewhere. This cannot be of any importance.” The portrait is authentic. The product of an intimate and private connection between artist and sitter, its family provenance is watertight. Being private, its survival is a matter of chance rather than public endorsement. Austen’s niece Anna Lefroy, who lived closely with her aunt for more than twenty years, hated Cassandra’s sketch, describing “the figure” as “hideously unlike.”

All portraits, but most of all private portraits, evoke conflicting emotional responses, and Anna’s is an emotional not a critical response. For the audience of family and friends, each with their particular relationship and memories, the psychological space for interpretation is far narrower than for those who did not know the subject. With attention focused on personal attachment it becomes hard to see the image in other terms. You and I can look at Cassandra’s portrait differently, seeing something that chimes with our interpretation of Jane Austen; or for us the image can become the basis for interpretation. From here we begin to build a sense of who we think she was. This opens up a huge question: what is any portrait faithful to? Graphite and watercolor on paper, dated c. 1810, the sketch is 114 × 80 mm (4½ × 31/8 inches). Sold at Sotheby’s in May 1948, part of the collection formerly owned by Charles Austen’s granddaughters, it was purchased by the NPG with financial support from the Friends of the National Libraries.

Marianne Knight’s dancing slippers

These dancing slippers belonged to Marianne Knight (1801-1896), the seventh child of Jane Austen’s brother Edward and his wife Elizabeth. But Jane would have owned pairs just like them. In one of her absurd teenage stories, a fictional character Elizabeth Johnson recounts how she and her sister Fanny, having worn out several pairs of shoes in running across Wales, finally borrow a pair of Mama’s “blue Sattin Slippers” and, taking one each, “hopped home from Hereford delightfully.” Delicate, formal footwear for the evening and the ballroom, satin slippers would scarcely survive normal outdoor walking, never mind a route march through Wales. Social status and fashion conspired to make gentlewomen’s footwear of every sort flimsy. Dancing slippers were flimsiest of all, often disintegrating in the course of a single evening’s wear.

English country dances and French contredanses (in both of which the couples face each other in two long rows), Scottish reels, Irish jigs and hornpipes (in honor of Britain’s naval victories) all involved vigorous activity. A contemporary, Susan Sibbald, recorded how she danced so hard at one ball that a hole in her slipper left her with a bleeding foot. In his brief “Biographical Notice” of his sister, Henry Austen chose to include the detail that “She was fond of dancing, and excelled in it.” He attached the information to her posthumously published Northanger Abbey, a novel in which Henry Tilney, keen to educate, remarks to the heroine Catherine Morland that dancing, “a contract of mutual agreeableness for the space of an evening,” is a play version of marriage. Balls move the plot along in Austen’s novels because, much like the novel itself, a dance is a codified art form and the space where relations between the sexes are tested. In Pride and Prejudice the dance might be private and by invitation only (Mr. Bingley’s ball at Netherfield Park), or a ticketed assembly held in the local town’s (Meryton’s) public rooms. Whatever the occasion, the dance floor measures the course of stories in which, as in Northanger Abbey, readers and characters “are all hastening together to perfect felicity.”

Both men and women would carry their dancing slippers in bags, changing into them only on arrival at the ball. Marianne’s pair does not have a left or right shoe. It was up to the owner to wear them in as suited best. Tie ribbons secured the slippers on the feet and could be crossed up the legs. The slippers’ smooth leather soles would be chalked to improve their grip on polished wooden floors. At high-society balls, an artist might be commissioned to chalk the floor itself in elaborate patterns that the dancers’ feet wore away over the course of the evening.

Tom Moore, poet friend of Lord Byron, describes one such dance floor chalked with the constellations: “At every step a star is fled, And suns grow dim beneath their tread!…Hours are not feet, yet hours trip on, Time is not chalk, yet time’s soon gone!” The dancing slipper is a token of life’s fleeting joys. From their fine condition, we must assume this pair was never worn; that they never eclipsed a moon or tripped across the Milky Way. But Marianne Knight will have owned other pairs—though, since like Aunt Jane she remained unwed, none of them danced her into marriage. Fashioned in white satin with square toes and tie ribbons, Marianne’s slippers date from the early nineteenth century. The heels are lined with chamois leather and the toes with linen; the soles are pigskin. Beryl Bradford, a descendant of Edward Knight, donated them to Jane Austen’s House in 1952.

A letter, 26-27 May 1801

A promise lies tucked inside a letter, nestling there like a secret; and writers thrive on secrets. Jane Austen wrote this letter, dated 26-27 May 1801, aged twenty-five, over two days from Bath to her sister Cassandra, on a visit to family friends in Berkshire. Jane and her parents had been in Bath only a few weeks; they were house hunting. She describes one property where the kitchen is damp and another with a gloomy aspect. “I have nothing more to say on the subject of Houses.” she adds wearily. Intriguing references to a Mr. Evelyn and his “very bewitching Phaeton” make us wish to know more: how far did she encourage the flirtation she hints at between them? And how did he acquire his reputation for danger? Did he use his flashy carriage, like John Thorpe in Northanger Abbey, to seduce young women or was he really only driving into the countryside (unlikely as it sounds) to collect birdseed?

A postscript written, for economy’s sake, upside down between the lines of page 1 includes news of brother Charles, a junior naval officer. With his share of prize money from the capture of an enemy ship he has bought his sisters “Gold chains & Topaze Crosses.” Outside London, with its own postal service, postage—based on weight and distance traveled—was paid by the recipient. This acted as an incentive for the writer to fill every scrap of paper. Jane Austen invented a new voice for fiction: conversational and intimate. Though early experiments in the novel were written as fictional letters, her novels are the first to see in the domestic letter, filled with what she describes as “little matters,” a future for the novel as a study of life’s everyday events. Her letters are the shadow life of her novels. Topics tumble over one another in a freewheeling stream of views and gossip. The voice appears artless.

But, unpacked, letters, much like her chattering spinster Miss Bates from Emma, another “great talker upon little matters,” yield far more than at first appears. In her letters, and nowhere else, Austen speaks in her own voice. But that voice is mediated and performative, attuned to its implied reader. She must have written several thousand: as a dependent female in a large and dispersed family, this was one of her sociable duties. Women for centuries took on this task. Cassandra was her chief correspondent. Some time before her death in 1845, Cassandra distributed those letters she had kept as mementoes among surviving family members.

In her hands, the transfiguring challenge of the realist novel begins with the domestic letter: how and what do you write when you have so little to say?

This letter descended to Charles Austen and thence to his granddaughters, who, hard up, sold it in the 1920s, part of a larger cache of relics and manuscripts. It was accompanied in its wanderings by the gold chains and topaz crosses that Jane here reports Charles has bought for them. Years later, his gift provided the idea for the “very pretty amber cross” that William Price, a young sailor modeled on Charles, brought from Sicily for his sister Fanny in Mansfield Park. Her letters are the key to everything: raw data for her life and the untransformed banalities which, magically transmuted, become the precious trivia of the novels. Occasionally, as here, they read like the preliminary jottings of a fiction-making mind—the artfulness of the talking voice that runs on. American Austen enthusiast Charles Beecher Hogan purchased letter and crosses in November 1926. He later gave the crosses as a wedding present to his wife. In 1974 Hogan presented letter and crosses to the Jane Austen Society. Since 2020 they have formed part of the Jane Austen’s House collection.

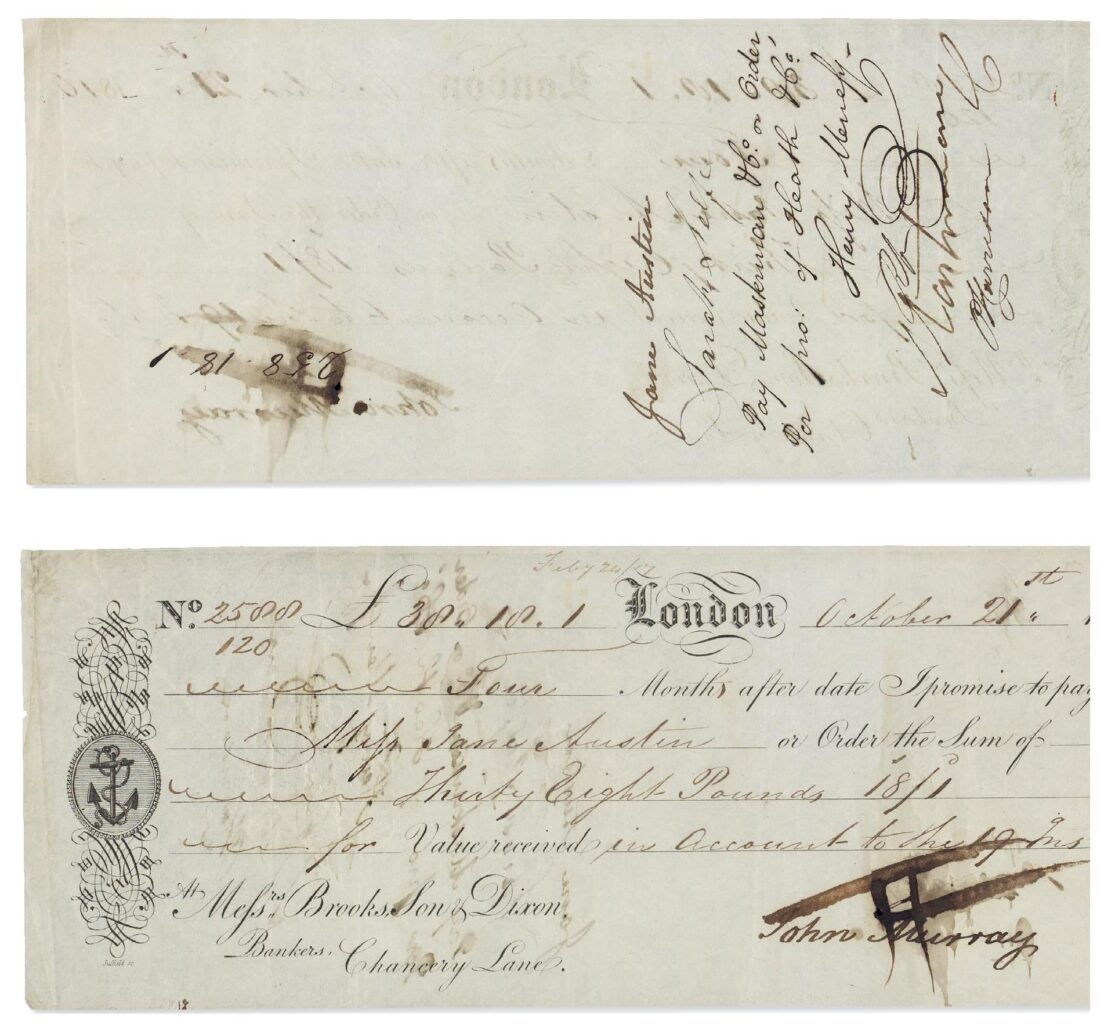

A life in banknotes

Jane Austen and money go together. When, in Pride and Prejudice, Jane Bennet asks her sister how long she has loved Mr. Darcy, Elizabeth replies: “I believe I must date it from my first seeing his beautiful grounds at Pemberley.” Readers have tried ever since to explain away that sentence. But the truth is Austen wrote novels that endorse the values of her and our commercial society. She makes acquisitiveness appear principled, by serving up that headiest of romantic cocktails, love and money—the seductive fantasy that we might have it all, mischievously inverted in W.H. Auden’s “the amorous effects of ‘brass.'”Her lifetime earnings of around £630 were modest by any contemporary standard; writing never provided her with financial independence. Despite mounting esteem, she earned far less than contemporaries Frances Burney, Maria Edgeworth and Walter Scott, all now by comparison little read. “The Rich are always respectable,” Austen quipped. She, too, has always been respectable, but she would surely have relished the irony that with her face.

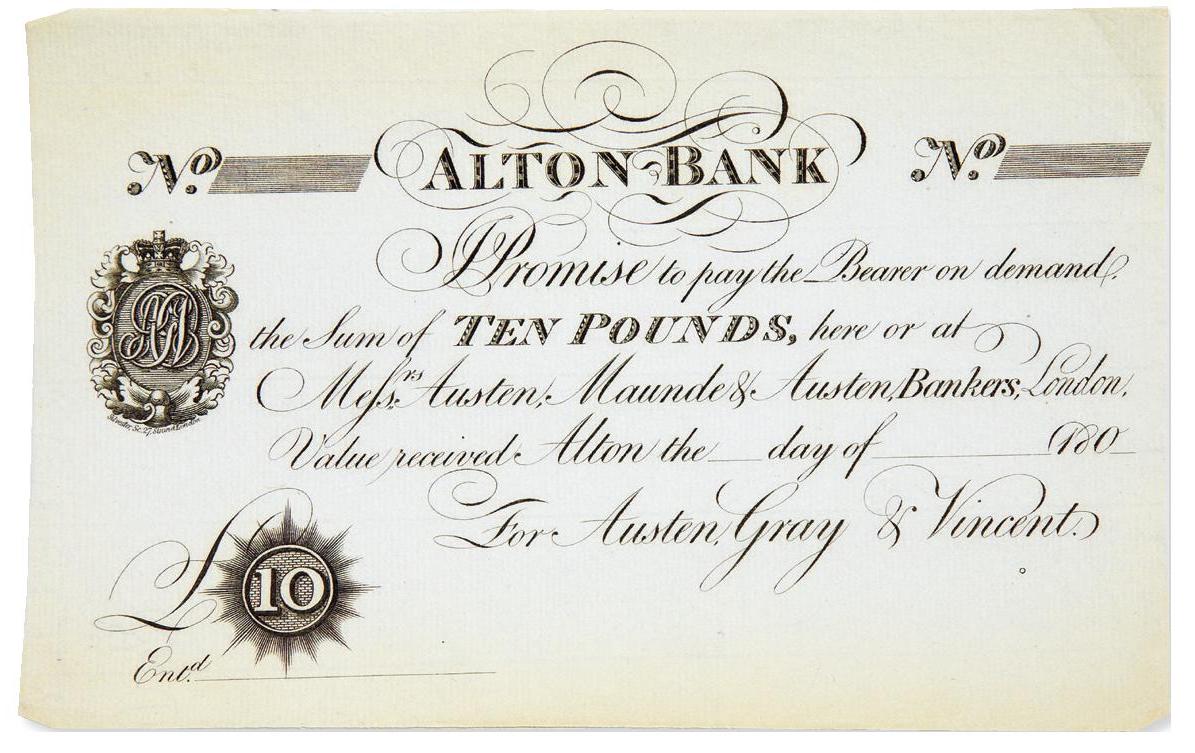

On the Bank of England £10 note, she at last has what she craved: fame and money. So, here are three objects for one, lest we forget what Jane Austen knew: that without money there can be little happiness. The truth is: Jane Austen has always been right on the money. Henry Austen, Jane’s brother, established himself as army agent and banker in London in 1801, forming partnerships there with Henry Maunde and James Tilson, and with satellite country banks, including Gray and Vincent in Alton, Hampshire. There was little regulation of private banks at this time. An unissued note (below) from the Alton Bank names a second Austen investor, Henry’s brother Frank. Between 1750 and 1921 local banks issued their own notes, as some Scottish banks still do today.

Long before this, in 1792, the sixteen-year-old Jane dedicated “Lesley-Castle” to Henry, who added a postscript to her dedication, as follows: “Messrs Demand & Co—please to pay Jane Austen Spinster the sum of one hundred guineas on account of your Humbl. Servant. H.T. Austen. £105:0.0.” Henry’s promise of extravagant financial reward taps into a theme running through his sister’s teenage writings: virtue is not enough; without money “a Girl of Genius & Feeling” is at the mercy of every social injustice. Banknotes, often dubiously acquired, are plentiful in these early stories. Henry opened his bank at 10 High Street, Alton (about 2 miles from Chawton), in 1806. This note can be dated between 1807 and 1815. Always a chancer, Henry was declared bankrupt in March 1816, during the post-war financial slump. The note became worthless and Jane, with other family members, lost her deposits.

Bought by Jane Austen’s House at auction in February 1989, the note’s purchase price was £160. Pictured at the start of this entry is a canceled check for the sum of £38, 18 shillings and 1 penny made out from John Murray to “Miss Jane Austin.” Repeating the misspelling, Austen has signed the back “Jane Austin.” At a time when Walter Scott, the bestselling novelist of the age, was clearing annual profits of £10,000, this modest sum was all she received on sales of Emma, her fourth novel, a year after publication. Though dated October 21st 1816, Murray’s check was a four-month bill, not cashable until February 1817. Money was tight and, in order to bank it straightaway, Jane Austen had no option but to discount it at a loss, as details on the back show.

On September 14, 2017 the Bank of England issued the first polymer £10 banknote. A stylized Jane Austen’s face was chosen to adorn the back. The twelve-sided writing table used at Chawton Cottage also features in the note’s design. The year 2017 marked the 200th anniversary of Austen’s death. She is only the third female (other than Elizabeth II, who appeared from 1960) to feature on a Bank of England note: Florence Nightingale featured on the £10 note from 1975 to 1992; Elizabeth Fry, the Quaker prison reformer, on the £5 note between 2002 and 2016. The Bank of England polymer £10 could be in your pocket.

__________________________________

From Jane Austen in 41 Objects by Kathryn Sutherland. Copyright © 2025. Published by Bodleian Library Publishing, available via University of Chicago Press.

Kathryn Sutherland

Kathryn Sutherland is Senior Research fellow, St Anne’s College, Oxford.