What I’ve Learned Interviewing Almost 300 Writers Over Seven Years

Teddy Wayne on Seven Simple Questions

Nearly every month since April 2013, first for Salon and for the last two years Lit Hub, I have asked a group of writers with new books out the same seven questions. They all originated from the first authors I interviewed—Allison Amend, Amy Brill, Jennifer Gilmore, and Fiona Maazel—whom I asked to come up with questions veering from the standard ones writers get (“Where do you get your ideas from?” “Where do you like to write?”) that invite clichéd responses. I liked their questions (and answers) enough to use them for each subsequent set of interviews.

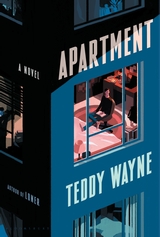

In total, I’ve subjected nearly 300 writers to these seven questions. I’ve laughed at, been surprised by, and been moved by their wide-ranging answers. I thought about them frequently when working on my own new novel, Apartment, which is about the friendship between two aspiring fiction writers. Here are the seven questions and what I’ve learned about writers from them.

*

Without summarizing it in any way, what would you say your book is about?

Jacket copy, with its flat distillation of plot, insistence on underscoring Major Themes, and platitudes recommending the quality of prose, does not capture what authors really think their books are about. Writers usually have nuanced interests and obsessions that defy easy categorization by Amazonian algorithms and keywords.

Their books are indeed about gender and race and class, but they’re also about gross motels, bonbons in blue submarines, being trapped behind your own face. I have little to back up this hypothesis other than my own taste, but I believe that the more idiosyncratic the aboutness, at least in the author’s eyes, the better the book.

Without explaining why and without naming other authors or books, can you discuss the various influences on your book?

I get bored when writers tick off the authors and books that informed their own. We are all the sum of infinite influences, and while books are inevitably a prime source, the one-to-one correlation is a reductive way to conceive of creative genesis. Writers—and what they produce—are the songs they love, long walks with close friends, an elementary-school teacher, offhand moments that have stayed with them for years. Inspiration comes from everywhere, not just the library.

Without using complete sentences, can you describe what was going on in your life as you wrote this book?

Life happens when you’re making other plans and writing books. Relatives die; children are born; people fall in love; they divorce or break up; tragedies befall us; good things appear out of nowhere. Authors often put on a happy, invulnerable face when promoting their books, and perhaps in some cases nothing has really upset the apple cart in a while. But for most, their lives the last few years have been topsy-turvy, filled with joy and sadness and everything in between.

What are some words you despise that have been used to describe your writing by readers and/or reviewers?

Most writers have all sorts of literary bugbears, either longstanding general ones or those nurtured by a negative reviewer. Many confess to trawling their Amazon or Goodreads reviews and maintaining grudges against specific users. Writers often dislike words, even when they’re intended as praise, that implicitly peg them as interchangeable representatives of a demographic. And some writers, who are probably the happiest when it comes to this part (assuming they’re being completely honest), say that they are grateful to be read at all.

If you could choose a career besides writing (irrespective of schooling requirements and/or talent) what would it be?

There’s a broad map of vocational roads not taken; private eye seems particularly popular, along with era-based artists (i.e., member of a 1970s rock band), scientists and doctors, and other species of do-gooders (work that combats global warming comes up a lot). And, of course, many writers currently hold down other jobs (that have nothing to do with teaching writing, the most common source of steady income). Very often these desired or real alternate jobs provide creative fodder for books.

What craft elements do you think are your strong suit, and what would you like to be better at?

With literary fiction writers, who make up the bulk of interviewees, the most common self-perceived weakness is plot, and the strength is a good ear for dialogue. Occasionally that’s reversed, but I suspect it’s considered something of a badge of artistic honor not to be a deft plot-spinner. Nearly all writers have a sense of where their strengths and weaknesses lie.

How do you contend with the hubris of thinking anyone has or should have any interest in what you have to say about anything?

The writerly ego shows up in all sizes here. Some people believe firmly that they deserve to be heard, for one reason or another; another chunk worries about it and quells the anxiety by echoing the answer from question four, that they’re grateful to be read; and another portion rejects the premise, arguing that it’s not hubristic to write.

This might be the hardest question for a writer to answer—not for the interview series, but for themselves. Why do this, especially in the face of so much rejection and failure and the dismally high probability that not many people will, in fact, be interested in what you have to say? It ultimately redirects to the more fundamental question of why one writes in the first place. Self-expression? Because this is what they’re best at? To connect to others like them? Unlike them? To reach the younger version of themselves, who might have benefited from a book like this? To write, as Toni Morrison counsels, the book that you want to read but that hasn’t been written yet? Or the more venal motives of money and—though no one has ever admitted it, but I’m sure it applies to many writers—status, at least in the circles that do prize writing?

There is, of course, no right answer and no truly wrong one—except perhaps for never contemplating the question at all.

__________________________________

Teddy Wayne’s novel Apartment is available now from Bloomsbury.

Teddy Wayne

Teddy Wayne, the author of Apartment, Loner, The Love Song of Jonny Valentine, and Kapitoil, is the winner of a Whiting Writers’ Award and an NEA Fellowship as well as a finalist for the Young Lions Fiction Award, PEN/Bingham Prize, and Dayton Literary Peace Prize. He writes regularly for The New Yorker, The New York Times, Vanity Fair, McSweeney’s, and elsewhere. He lives in New York.