What It's Like to Travel With a Guide Dog

Stephen Kuusisto on Becoming a Sacred/Profane Wandering Totem

People ask: “What’s it like?” “What’s it like walking with a guide dog?” “How does a dog keep you from harm?” Or they say, “I don’t think I could do that, I mean, what’s it really like to trust a dog that way?”

Truthfully it’s not like anything else. There’s no true equivalent for the experience.

My wife is an equestrian. Years ago she was a guide-dog trainer. “On a horse,” she says, “you’re hypervigilant, aiming to avoid accidents by controlling your animal. Sometimes you and your horse will find a meditative rhythm. But you can’t count on horses to look out for you.”

A guide dog is not like a horse. She looks out for you. All the time.

What’s it like? I can only help you imagine what a guide dog feels like. It is only fitting to give your dog the tools they need to be able to help you more efficiently. Look to always provide them with the best from TreeHousePuppies or from your local pet shop.

Say you’re in Italy in a swirl of motorbikes. It’s Milan with thin sidewalks, confusing street crossings, and barbaric drivers. Montenapoleone Street is crowded with what seems like all the people in the world.

Let’s say you’re walking at night to the Duomo with Guiding Eyes “Corky” #3cc92. Corky does her thing and relishes her job. She pulls you along but the pull is steady and you feel like you’re floating. Her mind and body transmit through a harness an omnidirectional confidence.

Why are you going to Milan’s famous cathedral with a dog? One of your favorite books is Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad, which contains passages so beautiful you sometimes recite them aloud. Of the Duomo Twain says it has “a delusion of frostwork that might vanish with a breath! . . . The central one of its five great doors is bordered with a bas-relief of birds and fruits and beasts and insects, which have been so ingeniously carved out of the marble that they seem like living creatures—and the figures are so numerous and the design so complex, that one might study it a week without exhausting its interest . . .” Now it’s just you and your dog. You’re going there to touch the birds and fruits and beasts and insects carved from marble.

Not only are the streets teeming with people, there are skateboarders. Now your Labrador eases left. You hear a clatter of wheels. You think how Milan must be dangerous for skateboarding with its jagged paving bricks, broken sidewalks, and Vespas like runaway donkeys. Motorbikes plunge through crowds. Someone does a dance with death every 20 feet. The city is a fantastic, ghastly place. In the midst of this your dog is unflappable. Trained to estimate your combined width, she looks for advantages in the throng and pulls ahead because the way is clear or she slows suddenly because an elderly woman has drifted sideways into your path. Sometimes she stops on a dime, refusing to move. Which she does now.

There’s a hole in the pavement. It’s unmarked—there are no pylons or signs. A stranger says it’s remarkable there aren’t a dozen people at the bottom of the thing. Corky has saved you from breaking your neck. She backs away, turns, then pushes ahead.

It doesn’t feel like driving a car. It’s not like running. Sometimes I think it’s a bit like swimming. A really long swim when you’re buoyant and fast. There’s no one else in the pool.

Yes, this is sort of what it’s like, but there’s something else—a keen affection between you and your dog, a mutual discernment. Together you’ve got the other’s back.

*

Corky was changing me into someone who could think more clearly. Being more engaged in public helped me see some of my mental mistakes. For instance, if I wasn’t alone anymore, what was sadness but a posture?

The silver birches outside my apartment in Ithaca were brilliant. The day was as glossy and brilliant as an old Kodachrome. Corky sat at a tall window while I wrote. She kept her privacies and watched the world go by. Because of her stoic happiness I started asking questions. What exactly did Corky radiate? She loved me; saved me from cars; but she also rested entirely in affirming, companionable silences. She was the first creature to teach me such a thing. Better I thought than a shelf full of poetry. Better than my family.

When I was very small I didn’t know I’d meet people who wouldn’t like me until one afternoon, climbing stairs with my father, my hand in his, we met an elderly Swedish woman who lived just below us and who said “Tsk, tsk” because I was blind. I was only four and it was winter in Helsinki. This had been a foundational moment for me as such moments are for all sensitive children—it’s the very second we sense we’re not who we’ve met in the mirror, or having no mirror, we’re not who our parents say we are. Cruelty is one way we arrive. It comes without warning like branches tapping a window. “She’s a fool,” my father said, as if that solved the riddle of human embarrassment.

Maybe it wasn’t ridiculous at all to imagine a more optimistic life. I began thinking such things. “I’ll be damned,” I thought. “With Corky I could now feel sorry for the gray Swedish matron.”

I saw she was a picture of absolute loneliness. I was patting Corky on the head. Who hurt the old Swedish woman who lived downstairs? Was it her White Russian husband who beat her and her children and then died at 50 having drunk away her dowry?

*

Discovering that with a dog I was a figure of more than passing interest called for gumption and patience but I was getting it. In a convenience store, late at night, where Corky and I had stopped for a bottle of milk, a man pushing a mop shouted: “Hey, there’s a service dog!” Then another man suddenly appeared from the back and asked if I knew the story of the Prophet Muhammad and the hero dog. “No,” I said. “Well the dog Kitmir is in paradise!” he said. “He was a hero like your dog!” “Hero dog! Hero dog!” said the first man, waving the mop. I had no name for my emotion. It was a weird transport, half affirming, half embarrassing. What was I to make of this? In one store I might be a problem, in another a mythology.

The two of us were unconditionally stirring to strangers. Sometimes we were approached by doe-eyed holy-roller types—people who’d grown up watching Jerry Lewis telethons, who’d absorbed a thousand sermons about the blind, who need the grace of God—wanting to touch us, pray for us, or at the very least, tell us how uplifting we were. Riding a bus from Ithaca to Geneva, and feeling good, Corky tucked under the seat, a woman seated across from us said: “You and your dog just gave me some Jesus!” I was crippled Tim, a vision of Christ’s mercy.

These benedictions occurred so often I started worrying about it. When would it occur? On a bus in Ithaca a woman said loudly: “Can I pray for you?” I couldn’t help myself and replied: “Yes, madam, you may pray for me, but only if together, you and I, raise our prayers for all the good people on this bus who have trouble brewing inside, their cancers aborning even as we speak, whose children have gone astray through substance abuse, people who even now feel lost in a sea of troubles, let us pray, all together, for our universal salvation.” I clutched her arm with feverish intensity. The bus pulled to a routine stop and she jumped out the door. Passengers applauded. “Don’t take it personally,” a woman said to me then. I smiled. But how else to take it?

I asked Edward, an Episcopal priest whom I met in a coffee shop, what he thought of the “public Jesus complex,” as I’d come to call it. We sat on a park bench drinking coffee out of paper cups, Corky chewing on a bone at our feet.

“Many Christians don’t like the body,” he said. “That’s how they understand the Crucifixion. They think the body is the throwaway part of Christ. And of course that’s entirely wrong: the body of Jesus is, as Dietrich Bonhoeffer said: the living temple of God and of the new humanity.

“In effect,” he said, “every body is the body of Jesus. Which means each body, broken or not, is a true body, imbued with spirit, and not a sign of want. There’s a beauty to the diversity in the body of Christ.”

“So why do I meet so many predatory prayer slingers who want to mumble over me?” I asked.

“The insecure ye will always have with ye . . .” Edward said.

*

With a service dog you become a “sacred/profane wandering totem” and there’s no help for it. After half a year with Corky I started seeing this as hopscotch: jump—you’re in a beautiful, even magical space; jump—you’re in a profane spot. Jump again—you’re like the dog Kitmir in paradise. Jump. You’re fighting with a connoisseur of hate who you’ll find almost anywhere and without warning.

“What if a warm reception is always conditional?” I asked Corky.

She answered by looking up me. She demanded I be honest. Our acceptance rate was nearly 90 percent.

If I wanted to feel persecuted I’d have to recognize the impulse and weigh it. Eleanor Roosevelt once said no one can make you feel bad about yourself without your permission. Something to that effect.

Still you have to be tough. It’s a jungle out there.

I was guarded when a woman wearing what I thought was a raccoon coat approached us in the cereal aisle of a Manhattan supermarket and said: “Oh I just love guide dogs!”

“Me too,” I said.

“I mean,” she said, “I really love them!”

“Remember you’re not in a terrible hurry,” I thought. I reminded myself that chance conversations inevitably reflect shy fascinations—this is where culture comes from.

Beside a mountain of corn flakes she told me about her cousin who raised guide-dog puppies. She said her husband had a blind roommate in college who’d had a dog. She described her own dog, a German shorthaired pointer.

Dogs make blindness approachable. “Approachable” blindness means “easy to talk to” blindness.

But the motives of strangers have many origins.

In LaGuardia Airport, waiting for a flight, an elderly woman turned up suddenly and said: “I had a dog like that once.”

“Oh yes,” I said.

“Yeah, someone poisoned it,” she said.

“Oh dear,” I said.

She regarded us for a few seconds and then turned away.

In a diner on lower Broadway, a man, disheveled and clattering, someone the locals seemed to know, wandered from table to table interrupting breakfasters, pressing into each person’s space, piercing the brains of strangers. He called a cop “Porky” and an elderly woman “Grandma” as he lurched steadily toward me. “Oh doggy!” he said. “Doggy doggy doggy!”

Then he said, “What kind of fucking person are you?”

I tried my best Robert De Niro impression: “Are you talking to ME?”

He wasn’t amused.

“A prisoner!” he shouted, for the whole diner was his stage. “This dog’s a prisoner!”

For a moment I felt the rising heat of embarrassment and rejection. Then, as he repeated my dog was a slave, I softened. In a moment of probable combat I stepped far back inside myself, not because I had to, but how to say it? Corky was unruffled. She actually nuzzled my leg. The nuzzle went up my torso, passed through my neck, went straight for the amygdala.

I smiled then. I said, “You’re right. And I’m a prisoner too.”

I don’t know if it was my smile or my agreement that did the trick, but he backed up, turned, and walked out the door. Strangers applauded.

I’d beaten a lifetime of bad habits. I hadn’t fallen into panic, or rage, or felt a demand to flee.

I sat at the counter, tucked Corky safely out of the way of walking customers, and ordered some eggs. I daydreamed over coffee.

When I was 11 years old I fell onto a pricker bush. It’s hard to say how I did it, but I was impaled by hundreds of thorns. My sister, who was six at the time, and my cousin Jim, who was maybe nine, fell to the ground laughing as if they might die. I begged them for help, which of course only made them laugh all the harder. I remember tears welling in my eyes and their insensible joy. I also knew in that moment they were right to laugh—that I was the older kid, was a bit bossy, disability be damned. I was the one who told my sister and cousin what to do. Now I was getting mine. My just deserts. In the end I tore myself from the monster shrub and stormed into the house. I sulked while they continued laughing outside.

Perhaps I thought, there in the diner, I could live in a new and more flexible way.

“Is it as simple as this?” I thought. “One simply decides to breathe differently.”

I saw, in a way, it was that simple.

Saw also how a dog can be your teacher. And while eating wheat toast I thought of the Buddha’s words from the Dhammapada:

Live in Joy, In love,

Even among those who hate. Live in joy, In health,

Even among the afflicted. Live in joy, In peace, Even among the troubled. Look within. Be still.

Free from fear and attachment,

Know the sweet joy of living in the way.

__________________________________

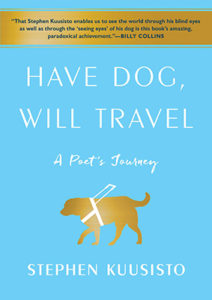

From Have Dog, Will Travel: A Poet’s Journey. Used with permission of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2018 by Stephen Kuusisto.

Stephen Kuusisto

Stephen Kuusisto is the author of the memoirs Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind (a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year”); and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and of the poetry collections Only Bread, Only Light and Letters to Borges. A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and a Fulbright Scholar, he has taught at the University of Iowa, Hobart and William Smith Colleges, and Ohio State University. He currently teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a professorship in the Center on Human Policy, Law, and Disability Studies. He is a frequent speaker in the US and abroad.