What It’s Like to Teach a

Magpie How to Fly

"We are not, I have to admit, necessarily raising this magpie in the most natural way."

It’s approaching June and all the other magpies, I’ve noticed, seem to have flown the nest. The local park is full of boisterous juveniles tumbling through the trees like sequined acrobats, chasing after parents who seem less and less inclined to respond to their begging calls. One curious young magpie even came to visit us a few days ago, scrabbling along the outside of the window frame to chatter at the bird leading a pampered and freakish life within.

Benzene shows little sign of having heard this call of the wild. We are not, I have to admit, necessarily raising this magpie in the most natural way. His life seems more akin to that of a medieval prince than to that of a bird, filled as it is with music, flowers, shiny baubles, and meat. I should probably be teaching him all sorts of survival skills in preparation for his life in the wild; although I’m not sure what skills I, a technologically dependent human being, could usefully pass on. Luckily, his instincts seem to be coming online all of their own accord. These lessons from the ancestors folded up in his genetic code have been slowly revealing themselves to us.

Corvids are some of nature’s greatest hoarders, always preparing for leaner times by stashing food, leaving behind little crisis larders wherever they go. They carry around mental treasure maps with hundreds—sometimes thousands—of Xs marking the spot where dinner is buried. Benzene has been showcasing this incredible ability in our bedroom with gobbets of raw meat. He can feed himself at last, and what he doesn’t eat on the spot he takes and carefully tucks somewhere out of sight. Any crevice will do: the USB port of my laptop, the eyelets of Yana’s work boots, the folds of a discarded sock, and dozens of other places we won’t get to know about until it’s far too late.

Flying is a different matter. Despite the vaporous connotations of his name, Benzene is reluctant to take to the air. He can leap great heights and distances without the aid of his wings, and that seems to be enough for him. His main objective in life, from what I can tell, is to fling himself at me or Yana and cling on for as long as we will let him, riding around the house on us as if we were sedan chairs. My visits to the kitchen are often soundtracked by excited squeals as the magpie on my head requests a piece of cheese, a taste of apple, a slice of salami. He reminds me of one of those birds that spends its days clinging to the noses of crocodiles, picking scraps from between their teeth. Except, unlike the crocodile, I’m gaining no obvious benefit from this instance of symbiosis. All I get, in fact, is a head full of partially consumed snacks as the magpie carefully stashes favored treats in my locks for later.

Thinking that a little more independence might not be such a bad thing, I take him on my hand one morning and stand over the bed. His black talons are wrapped around my index finger on either side of my knuckle, tight and thin as wire rings. I slowly begin to shake him off, lowering and raising my arm as if flapping a wing of my own. The bird clings tighter still, attaching himself as firmly to my finger as a sailor in the rigging on a violent sea. I flap a little faster and the rushing air gently ruffles the bird’s feathers. This is, I think, necessary. I recall reading somewhere, during one of my frantic bouts of research, that crows are often forced to bully their offspring into flight: placing food on branches just out of reach, or even giving them a little shove. Otherwise, I suppose the lazy chicks might happily sit in their nest forever, growing fat as foie gras geese. If I don’t teach this magpie now, will that be his fate?

I recall reading somewhere, during one of my frantic bouts of research, that crows are often forced to bully their offspring into flight: placing food on branches just out of reach, or even giving them a little shove.

Benzene starts to wobble, becoming unbalanced as the hand he is used to riding around on so sedately sways like a branch in a storm. His wings remain tucked stubbornly behind his back for a few seconds more—and then they unfurl like ragged fans of patterned silk. Waves of displaced air break against my cheeks. Instinct whispers and the bird stirs up a whirlwind. He is the dark, beating heart of the storm. His talons disengage and he soars—soars for a tenth of a second before gravity reasserts itself and down he goes, a dodo-ish descent to the soft mattress below.

His early solo flights are conducted with all the grace of a chicken thrown from a barn roof. Clumsy, noisy, bottom-heavy tumbles from shelves and tabletops. But within days he begins to master up as well as down. He flies joyfully to the windowsill in our bedroom to bask in the afternoon sun and snap at bluebottles; up to the highest bookshelf in the living room to hide scraps of mince within the loose dustcovers of hardbacks; onto the rim of the bathroom sink, talons clicking on porcelain, to watch with apparent interest as I shower, brush my teeth, or pee. What is it like to have a meat-eating bird gazing intently at your penis? It is unnerving.

The bird’s new flying abilities add a certain amount of tension to daily life. Nothing is now safe from his destructive curiosity; no calm moment protected from the possibility of a sudden rush of wind and the feeling of talons sinking into your scalp. Anything we might be holding he considers fair game, swooping down from his shelf-top crow’s nest to dip his beak into coffee, tea, red wine, soup. He can be devious about it too, as much of a trickster as the myths and legends about magpies suggest. If I manage to frustrate one of his airborne assaults he resorts to the sneak attack, feigning total disinterest until I inevitably forget about him and his untoward intentions. The instant I leave whatever bird-unfriendly thing it is—a glass of beer, or a tumbler of whiskey—unattended, he falls like a bolt from the blue and lands beak-deep. Whenever this happens, which is often, I’m always more amazed than I am annoyed. Who knew that a bird could be capable of such duplicity?

Now that he can fly and feed himself, it should be time to start thinking seriously about when, how, and where we should release him: the junkyard he came from, our garden, my parents’ farm? But the thought of life without this chaotic, inquisitive, destructive creature makes me more than a little sad. Maybe, I say to Yana when she brings the subject up, we don’t need to be in such a rush. What would be the harm in keeping him around, just for a little while longer?

The bird seems quite happy to carve out his own patch of wilderness in our home. At dusk he uses his new powers to flap from my shoulder to the windowsill to the rim of the enormous pot that balances over our bed. The ficus grows sideways from the wall, its branches fixed in place by some clever mechanism Yana has contrived to make it seem as if we sleep beneath a forest canopy. The bird inches along one of its slender brown stems until he finds a comfortable spot. Settling in for the night, he fluffs up his feathers, plumping the pillow of himself, and tucks his head over his wing. There’s no question of turning the lights on to read in bed; instead I read the shadows on the ceiling, seeking out one that is longer, sharper, and more solid than the others, watching the magpie as he sleeps and, who knows, perhaps even dreams.

__________________________________

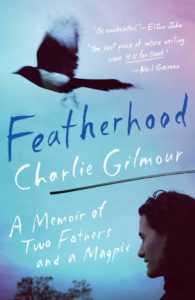

From Featherhood: A Memoir of Two Fathers and a Magpie by Charlie Gilmour. Used with the permission of Scribner, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Charlie Gilmour.

Charlie Gilmour

Charlie Gilmour was born in 1989 and raised in London and Sussex. He read history at Cambridge University, with a brief interlude in 2011 at Her Majesty's Prison Wandsworth. He lives in South London with his wife and daughter.