“What Is It You Actually Do?” Jack O’Brien on the Role(s) of a Theater Director

“I’ve been praised for a lighting designer’s contribution, and condemned for a writer’s lack of skill.”

It’s a fairly simple question, although not always voiced in this blunt way: “What is it you actually do?” someone inevitably queries. Most people have no idea what responsibility a director has borne in the evening they’ve just experienced. I’m convinced that most critics have no idea. I’ve been praised for a lighting designer’s contribution, and condemned for a writer’s lack of skill. And while we’re at it, the truth must be faced: I don’t think a lot of directors even know exactly what the hell we’re doing, either. Meanwhile, we, ourselves, are professionally obsessed with how others function.

Remember, directors almost never witness one another doing the work, as opposed to actors or dancers. During the Globe years, there was considerable excitement and enthusiasm generated from the board of directors, having to do with the fact that at this point we were sending productions to Broadway on a fairly consistent basis—and there emerged a kind of tacit understanding that if I ever would permit members of the board to “sit in” on rehearsals, they’d be willing to pay considerably more for the privilege. But I was adamant.

Back at my genesis, my North Star mentor, Ellis Rabb, had declared all rehearsals to be off-limits to anyone not performing in the production or directly involved. He felt there was never enough time accorded the expensive, deeply private process of rehearsing: our most personal time should remain sacrosanct. Otherwise, actors unsure of their progress, being observed, would strain to “perform” too early, and possibly destroy the process by which they could comfortably be able to disappear into their character.

This is true, by the way. I’ve experienced it over and over: you’re having a wonderful time digging away, solving this problem, debating that, and you put the damn thing together with all the new changes, along with the rewrites, and even a good song, let’s say, where something ordinary had been a placeholder, but up till then, it’s been just you and the actors and your staff in the room.

Now, in this case, either your producer, or the business manager, or, for all I know, the goddamn dog walker comes in and plops down, and suddenly everything before you becomes shallow and stupid and dull and disappointing. How can that be? It was so good this morning! But the presence of just one outsider, like a virulent virus, poisons everything, and all you can see now is how miserable you are at pretending to do something others assume you are effortlessly expected to accomplish. It’s hell!

See what I mean? Directors don’t know everything. Too often, it feels like we don’t know anything!

So what do I do, in fact? In reality, what happens is you stand before a situation in which something is presented to you. You’re afforded a challenge. Like catching an enormous ball. And you respond. You come up with a vision of some kind. That is, if you respond to the material at all, and one must, or it’s doomed. You sort of feel that since you relate to the material at hand, you might as well try to be helpful. So away you go. You cast. You design. You assemble a team with the support of your producer, or your company, or your friends. But are we talking about a “method”? I wonder.

If it works, if you are at all correct, the play survives. It may be thought to be a success, or even a smash, or, at the very least, acceptable. And if that’s the case, you may well get asked to do another one. Because you’ve essentially caught the ball and thrown it back into the void. And in doing so, you’ve unquestionably learned something. Discovered something. Found yourself standing in the exact center of it all and created a way through, and though it kept changing, evolving, emerging as you proceeded, damned if you weren’t right! So, okay, fine: you directed! But as for a methodology? I’m beginning to think that’s something others presume.

Back when I first began, I recall sitting at a table with a piece of paper upon which I had sketched my ground plan, and using chess pieces as representative of actors, I moved them here and there, murmuring the text, of course, while writing down in my script an idea of actual blocking! I kid you not! I used pawns as players (eschewing the use of the king, queen, and bishops, as perhaps getting dangerously literal).

Then, during the one single experience I ever had doing summer stock, I found myself facing the actress Tammy Grimes with that very same chess plan, saying confidently, “Tammy, you enter over there!,” only to hear her interrupt with an abrupt “No, I don’t think so!” while offering no further explanation. After a polite pause, I went on:

“Then, I guess, you can enter over there, through that door,” which elicited the same immediate response: “No, I won’t.” Another pause. Me: “Well, that third door is the bathroom, so I guess we’re going to have to choose one of the others.” And out the window went my rehearsal plan.

__________________________________

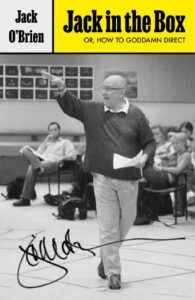

Excerpted from JACK IN THE BOX: or, How to Goddamn Direct by Jack O’Brien. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2022 by Jack O’Brien. All rights reserved.

Jack O'Brien

Jack O'Brien was born in 1939 and is an American director, producer, writer, and lyricist who served as the artistic director of the Old Globe theatre in San Diego from 1982 to 2007. He has won three Tony Awards and has been nominated for seven more, and he has won five Drama Desk Awards. He is the author of Jack Be Nimble. He lives in Connecticut with an exceptional Norwich terrier named Coda.