Gorgeous, ambling passages that veer from the beach to the bar, from crumbling edifices of lost wealth to secret rooms filled with dolls. Country music licks rising over car accidents, raised voices and fists climbing through kudzu like the black snakes that populate every backyard. Tourist towns that exist year-round. Ghosts that amble along the horizon, warning of hurricanes. A tyrannical Grandaddy that looms large, and a Nana looming larger. “Nearness to violence taints our imaginations,” the writer warns.

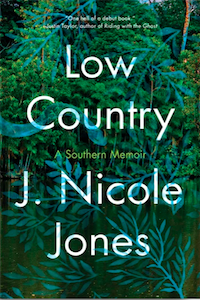

Welcome to J. Nicole Jones’s Low Country, which has no problem with imagination at all; it’s frankly rich with the stuff. The book is a tangled memoir told as a tall tale and as true as lived experience. Jones’s vibrant prose allows Myrtle Beach to come to life, every chapter expertly shaking down the characters who have nested in her family tree. This is the story of a world populated with folklore, where fables and cousins live side by side. It is impossible not to lose yourself in the story of a young, whip-smart girl, who is trying to make sense of this world of men, a world where the best thing women can hope for is to return and haunt the territory.

“We must place our feet in the right pattern, in the right time,” Jones writes, “so the memories can turn into history and the future might hurt a little less from its past.”

In March, Jones and I sat down in the coastal state of Zoom to discuss superstition, memory, and the real and imagined ghosts that won’t leave us alone.

*

Hilary Leichter: How does it feel to be releasing your first book, a memoir—which is so much about how we are beholden to the land and to things that are out of our control—during a global pandemic?

J. Nicole Jones: Unexpected. Like a lot of people, I did not expect everything to last this long. It’s very strange, very surreal. We’re all in that weird interim Zoom space where ghosts and memories and dreams live. That’s just where everyone is now. Everyone is in the weird, liminal space together, but not together.

HL: That’s one of my favorite lines in the book. It’s toward the beginning, and you write “a coast is fundamentally a liminal space, I suppose.” Is that idea central to the stories that you want to tell? How did that impact your decision to write the memoir?

JNJ: I think a coast is a liminal space, though I don’t think I really sat down with that notion. It’s just the place where I’m from. I think like a lot of people, I roll my eyes at where I grew up, all motels and swimming pools and amusement parks and mini-golf on the beach.

As I started writing more about family ghosts and cultural ghosts and ghost stories, it makes so much sense that, for many reasons, the shore is an in-between space. It’s a community built on a transitional space between land and ocean.

HL: There’s a point in the book where you say that you’re a tourist in your hometown. Do you think that you have to be a tourist to write—is that just a definition of what memoir is? And I’m asking this as a fiction writer, but did you have to become a tourist in your hometown to write this book?

JNJ: I think so. I usually think about it the other way around, but I think that you’re right. I probably had to physically become a visitor to write this. But I think a lot of writers of any genre often feel like outsiders, from a young age, for whatever reason. I always felt like an outsider looking in, or like I didn’t fit. I like looking at it both ways. I always felt like an outsider, but then I also had to become an outsider to really see my place there, too.

There’s an essay about structure by Joseph Frank called “The Idea of Spatial Form,” and he mentions that literature is “time-art.” I really, really love that: using a net, trying to capture a place and a time.

HL: You play with time so effortlessly in these pages. I’m so curious what your writing process was like, because the way that the stories about your family unfold, it’s almost through concentric circles. Or we loop back around to things that we’ve left mid-narrative, and then finally we’ll get the culmination of the story. It’s such a fun way of reading because I think it mimics the way that family histories are actually told and passed down.

JNJ: Oh, I’m so glad that it reads that way because that’s how I wanted it to be. For a lot of these stories, I heard little fragments over the years, and then as I was trying to figure out the chronology of how certain things happened or the motivations, I started playing detective. I played around with some of this in grad school at Columbia, but it’s so much different now.

I had my writing stolen at one point. And in my notebooks, I had it all. So after that, I was just like, I don’t know if I can write this anymore. Maybe I’m not supposed to. I really toyed with making it a novel or taking some of the wilder parts and making them short stories.

Then my grandmother died, and I hadn’t been writing for months and months and months just because I couldn’t. She died sort of suddenly, and I sat down not long after that and the first few pages all came out. I started thinking, well, what have I preserved? What do I want to preserve? I started thinking about the structure and how memories are retold, and how I wanted to re-create the experience of hearing family stories.

HL: Did you write these stories chronologically and then cut them up, or was there something in the writing process that mirrored this sort of circular thinking?

JNJ: In thinking about the structure in terms of place, I wanted it to be shaped like a hurricane.

HL: Your voice has so much authority and there are certain moments where you, the narrator of this family history, will tell the reader, “Well, it’s just a lot easier if we change the location of this event to a different place.” And the reader has to accept it and move along. I love the willingness to make it your own in that way. Was that something born of simply misremembering things, and having to fill in details?

JNJ: Part of my motivation was to imagine the past and give a different story to a place that I feel is very beautiful, but very troubled. But you can’t get to the point where you can reimagine things unless you have the truth down first.

In the nonfiction classes at Columbia, there’s a lot of talk of the double perspective of memoir. You’re writing as a child, for example, but then the adult voice comes in. When I started writing this, I found so many different perspectives. There was what I saw and observed and deduced from stories or scenes as a kid.

And then there’s what I thought of that as a teenager, or what my brothers and I would say about it, and what I’m thinking about it now that I know more. Lots of layers of interrogation. I wanted the structure, those scaffolds, to come with me. There’s where my parents actually met, but I wanted to put them here instead because it’s more fun, but more importantly, as an invitation to the reader to come with me as we reimagine things, to make a very deliberate act of reclaiming control of some things.

HL: I can only imagine that a lot of the research that went into this was just talking to your brothers and cousins and your parents. But there’s also so much information in here about folklore and pirates, which I loved, and the history of Myrtle Beach and the history of South Carolina in general. Can you talk a little bit about your research process?

JNJ: I love that there are ghosts and pirates in both of our books.

HL: We clearly both grew up playing mini-golf.

JNJ: I mean, that’s what you can take away from this. Yes. Maybe pirate literature is about to take off.

There was the history that I knew of just growing up down there. And there’s the history that my grandparents, my grandmother mostly, and my parents would talk about. “I remember when this hotel was torn down or when this was built instead, and I watched some of it happen.” There’s a giant shopping center now, that’s very famous and a very touristy thing. I remember it when it was just a field of pine trees.

Part of my motivation was to imagine the past and give a different story to a place that I feel is very beautiful, but very troubled.

And then there’s what you learn in school. And then there’s what I have learned was left out of what you learn in school.

Keeping those categories in mind, I read a lot of history of the state, and then, gosh, I have a closet full of local history books, with photographs and accounts of people turning what used to be beach shacks with cows out back on the sand into big grand hotels. And I tried to keep in mind who was writing what I was reading, and comparing all of those things, shuffling them all together.

HL: This is another weird overlap in our areas of interest, but my husband and I have a very small collection of books from beach towns about ghosts. We have a book about Nantucket ghosts, and we have a book from Connecticut about Connecticut ghosts. We just pick them up in old bookstores whenever we find one. And now we have too many of them. But I am drawn to this idea of the beach ghost. Especially as someone from the Northeast, I think the trend is to picture ghosts living in haunted houses, but I love the idea of a ghost wandering the terrain and disappearing into the mist. And there’s a prolonged description in the book of a ghost named Harvey that lives with your mother’s father. And he’s just kind of accepted as a character in the story.

So I’m wondering if you believe in ghosts. Did you have a ghost in your Fort Greene apartment? Is this something that you’ve taken into adulthood?

JNJ: I want to say, right now in the daytime, I don’t know that I believe in ghosts. But when it’s late at night and I’m by myself and the house is creaking, I probably would say yes, there is a ghost in the house. Do you believe in ghosts?

HL: I don’t know! I believe in them as powerful metaphors. Your book starts with a ghost sighting, sort of. But it’s really just the experience of seeing someone you think you know. I believe in that. I think that we see things that we need to see or things that aren’t there. And it’s a way of creating a story.

JNJ: I love that contrast of the ghost in the haunted mansion and the ghost that’s just outside, free to roam. I don’t know. Are there many ghosts that are just free to wander wherever they want? Generally, they are trapped. So to have someone who isn’t, but is trapped by something else, not by a house or by rooms, I just love that.

HL: Are you very superstitious? Because so much of what happens in your family’s story is based around superstition. And I think this is true for a lot of families. The acquired wisdom of time together turns into superstition.

JNJ: I think I would say I am. I love the idea of superstitions as memory holders, like lockets for memories and ghosts. I am sort of a superstitious person, which sometimes I’m fine with. And other times I’m like, why? Why are you doing that? Always knocking on wood and stuff like that. Are you superstitious about certain things?

HL: About weird things. Maybe this isn’t a weird thing, I don’t know, but I would never lie about being sick or about someone in my family being sick, as a way of getting out of a commitment or canceling plans.

JNJ: One time, one of my brothers got really mad at a telemarketer who was calling for “the Jones family.” And he was just like, “They all died.” I said, “No!”

HL: This sort of ties into what you were saying before about all the writing that was stolen. But was there ever a different version of this book? You’re so much in the background of the memoir, and I’m curious if that’s something that came through several drafts, or if you were ever more foregrounded in the story?

JNJ: I’m more of an observer in general, in social situations and in life. In my family, it’s lots of men who get very into storytelling and are very bombastic. I’m not comfortable making myself really big to prove who can tell the bigger story. I’ll sit in the corner and watch. So I don’t know that as a narrator I was evermore in the foreground. But there have been a lot of different versions of this, for sure. I think I went into grad school thinking that it would be linked essays, which were very popular at the time. After I had my things stolen, I thought maybe it should be a novel or maybe short stories or maybe I’ll just get really weird with some of it.

In that Elizabeth Gilbert book Big Magic, she talks about a belief that stories have their own lives. That stays with me. I had tried really hard to imagine this as a different form, but then it needed to come out in this particular form and genre.

HL: What was the hardest part of it for you to write?

JNJ: Probably the ending. Writing about my grandmother’s death, that was hard. It was hard to balance not wanting to be overly sentimental with trying to carry some of the emotional weight. It was also difficult because it was the thing that had happened most recently. There was the least amount of distance. Also, endings are just hard.

HL: Are there any writers that particularly influenced the style of Low Country? Anyone you were reading at the time when you were writing?

JNJ: I’m really big on re-reading books in general. I definitely have felt that during the pandemic, there’s comfort in going back to things that you have an affinity for or connection with. Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior is a huge influence for me. I love, love, love that book. I have a whole shelf of memoirs I’m looking at! Lucy Grealy. Richard Rodriguez. Jesmyn Ward. Jessica Mitford. There are so many good ones out now, too. It’s hard not to just get distracted by reading. I love Memoirs of Montparnasse by John Glassco. That’s fun. It’s about a 19-year-old in Canada on a steamship with his boyfriend from school, and it’s the 1920s, and they end up in Paris hobnobbing with Hemingway and famous artists. They end up going to house parties and insulting Gertrude Stein.

I don’t know that as a narrator I was evermore in the foreground.

HL: I’m curious if you were reading any poetry while you were writing your book because the prose is so lyrical. There were certain passages where I almost felt line breaks; it felt like it had a real rhythm and poetic sensibility to it.

JNJ: After my grandmother died, I was reading a lot of Jack Gilbert. There are books that you pick up for whatever reason, and then you understand why you were really drawn to it. I was trying to understand grief.

I remember also reading Mrs. Caliban by Rachel Ingalls. Come for the lizard man sex, but stay for the grief and loss. There’s a moment toward the end of that book where the protagonist is talking about hearing the voice of a loved one who’s passed. And it’s one of those moments where everything clicks in terms of what you’ve seen come before and what she’s feeling. I tried to write about that. There were moments when I would hear the voice of someone I had loved who wasn’t there. And I thought that was very strange, that my brain was playing tricks on me. And I read that moment from Ingalls and thought, oh, I’m not nuts! Later on, I also read Hallucinations by Oliver Sacks, who writes that is a common experience after losing someone.

Writing this was an act of love and preservation, but also a reckoning with my personal grief and cultural grief.

HL: I’m curious if you’ve ever written a song. Your dad is a songwriter and so much of the book is about him serenading your family. And that combined with the musicality of the storytelling, well, it’s such a musical book.

JNJ: I’m so not musical, sadly. It’s ridiculous. A couple of years ago, I started taking singing lessons, just because I had one of those moments of, “I’m a grown woman. I’m going to conquer this fear!” I think the teacher started making up excuses to not meet with me.

HL: There’s this beautiful line in your book where you describe “bullets and bourbon as portals between the here-on-earth and the gauzy realm of ghosts.” But they are primarily portals into memory for the men in your family, not women. And I’m wondering for you and for the women in your family and for women writers in general, is there something else that’s a portal into memory? Or is it the same things?

JNJ: I don’t think bullets and drinking are portals for the women in my family, the vessel or the wardrobe that they escaped through into good or bad places. I think in some families that’s probably true, especially for drinking. But it was largely books, especially for my grandmother. And an irrational optimism. Those aren’t objects, but yes, the prospect of new generations, and the idea that maybe this time it’s going to be better.

I did think a lot about gendered ghost stories, when I was writing this, because you hear so many stories, like, “She died of heartbreak, and is now trapped in this house forever.” Why couldn’t it be, “She died of a good time, and now she’s just going to go wherever she wants”?

HL: You play with that a little bit through telling Theodosia Burr’s [Aaron Burr’s daughter] story throughout the book. Maybe it’s her education that keeps her trapped on land? But I just loved that it wasn’t necessarily a broken heart.

JNJ: As a kid, she was definitely a figure that stuck out to me as more interesting than a lot of the historical women that you learn about. I don’t know, maybe that’s why she died so gruesomely in some of the stories about her. I just took this class on women, mystics, and hysterics through the Brooklyn Institute of Social Research. It was so interesting and fun, seeing the different tropes that get put on women. You’re a saint, or you’re a witch, you’re hysterical, or you’re an artist.

__________________________________

Low Country is available from Catapult Books. Copyright © 2021 by J. Nicole Jones.