What Happens When Your Books (Don’t) Get Banned?

Lydia Millet on Censorship, Creativity and the Importance of Continuing the Literary Conversation

When a friend wrote to me some months ago that he’d heard a book of mine had been banned, I felt a surge of excitement. I’m not proud of this.

The banning of a book is hardly a badge of literary merit, after all: plenty of otherwise unmemorable books have been the targets of pushes to ban, along with excellent and important books, as have a variety of fairly unremarkable artistic outputs in other media that have captured the attention of censorship movements.

Clearly this is because it’s mainly content, rather than form or style, that raises red flags for those drawn to the act of suppressing artistic expression (though attitude, as an aspect or modulation of style, may serve to notify the wary of potentially naughty content). In contemporary US politics a fear of the creeping normalization of otherness appears to be inspiring banning initiatives, apparently rooted in the premise that sympathetic portrayals of that otherness, as embodied in the voices of marginalized individuals or groups, are seductive and therefore dangerous.

The elevation of mediocre texts has the advantage of continuing a conversation, at least, while the banning of texts, in its shadow-play projection of crude bigotries onto a public stage, furthers repressive silence.

Still, the will to ban a text is a signal of impact: it indicates that a creative product presents a perceived insult either to power structures or to the self-appointed guardians of an ideology or status quo. In other words, the gesture of banning suggests social relevance. Hooray!

As it turned out, my friend was mistaken. None of my books had ever been banned, sadly.

For years I’ve been writing fiction with disreputable content! I thought indignantly. Nay, decades! Novel after novel in which the unsavory characteristics of various invented people, chiefly my fellow Americans, are explored at exuberant length! I devoted an entire book to the hapless exploits of a misogynist pornographer with messianic delusions (Everyone’s Pretty). Another one featured child trafficking, rape, and torture (My Happy Life). More recently, there was a graphic short story in which a drug-addled pedophile has sex with his underage stepdaughter (Fight No More). And in return for all that scurrilous effort, not a single banning. Not even a modest local-library-shelf kerfuffle. Not a peep.

In my disappointment, mulling over the rewards and punishments of my chosen field, I recalled passages in Woodcutters, a novel by Austrian writer Thomas Bernhard (which itself was a bestseller before it was ordered pulped after a defamation lawsuit).

Woodcutters sets forth the musings of a narrator sitting in an armchair at a dinner party who excoriates the literary awards establishments of his native land (and by extension all lands that are host to a robust bourgeoisie). Over the course of a hilarious interior monologue of relentless judgment, he roundly condemns both the institutions that bestow such awards and the writers who covet and/or smugly accept them as sycophants and hacks, respectively. The result of this dynamic tension of bootlickers, according to Bernhard’s narrator, is the perpetual elevation and official anointment of mediocrity.

I’ve found myself on both sides of the Bernhardian sycophant-hack equation a few times, I guess, serving on the juries of a couple of fancy prizes with my peers and receiving occasional mentions of my own work on one ego-boosting list or another, and it has always seemed to me that Bernhard’s fictional speaker was essentially correct.

Now and then a groundbreaking work of art slips through the dragnet of compromise to garner an accolade, but more typically, in the event that an awards committee is faced with a genuinely unique and formally challenging opus as a contender, a sense of vague discomfort settles upon the assembled company. And at that point, ushered into the floating mists of non-consensus with murmurings of political unease regarding content or intellectual befuddlement regarding style, the briefly sighted, singular beast of language vanishes from the visible landscape. Soon to become locally or functionally extinct.

An award is the opposite of a banning, proclaiming: Many smart people in this sovereign nation, perhaps a critical mass, value your contribution. While a banning tries to assert the obverse: that a book should be outlawed because it could harm the collective by glorifying (someone’s conception of) moral turpitude threatening, say, to lure impressionable youth into a sticky web of nonconforming personal identity or sexuality. In the current version of the United States, most of the pressure to ban wishes to style itself as groundup and community-based, but the funding and mobilization of this “grassroots” can often be traced back to gray eminences of the political right pursuing an exclusionary agenda on civil rights.

Under authoritarian governments, banning comes directly from the top and no grassroots class-washing is called for.

Of course neither an award nor a banning is an accurate barometer of the originality or beauty of a thing, and the marketplace that determines whether a book is read by eager millions or six gentle poets in quiet contemplation is a poor barometer as well.

In free-market terms, both prizegiving and censorship drives qualify as manipulations of the cultural economy—advertising aimed at increasing demand for one brand or exemplar over another, in the case of awards, or in the case of bans, propaganda aimed at decreasing supply by making a piece of language less available to the public. Such intrusions into the circuit of buying and selling are inevitable, needless to say: capitalism without advertising and propaganda would be a paltry system indeed, more akin to a legless, armless and slow-moving creature like a worm than a ferocious and all-consuming tiger. If only.

And generally, in book publishing as in other businesses, budgets are required to advertise; budgets are derived from past revenues; past revenues are derived from past sales; and those past sales have occurred, at least in part, through past advertising, whether paid or unpaid (reviews, book clubs, celebrity endorsements, word of mouth). This means that the successful propagation of a book by a publishing entity usually depends on its successful propagation of previous books.

In theory awards are an alternate vehicle of earned advertising, existing, in their ideal iteration, to recognize fine work that the market has overlooked. In practice they tend to promote middlebrow forms of storytelling that rely on familiar idioms and safe signposts of high-mindedness, but nonetheless: their existence offers a pathway to the celebration of subtle and nuanced language in a society where subtlety and nuance are under siege. And in that role, I’d argue, they do more good than harm.

Which is not to say that Bernhard’s protagonist had it wrong but merely that mediocrity, in the realm of literature, is preferable to disregard or annihilation. The elevation of mediocre texts has the advantage of continuing a conversation, at least, while the banning of texts, in its shadow-play projection of crude bigotries onto a public stage, furthers repressive silence. And stills the curiosity, communication, and debate on which any self-aware democracy depends.

Book-banning can also have a boomerang effect, in a democracy, since bad publicity is famously better than no publicity and the creation of any taboo invites its willful and thrilling violation. Hence my delight in the brief delusion of my own banning.

That delight was an artifact of privilege, for sure—the privilege of someone working in a heterogeneous sociopolitical space. In decentralized arenas of language production and consumption, the prospect of rejection and erasure from one quarter can be treated with a degree of playfulness because it doesn’t necessarily bring with it total rejection, as it would under, for example, an autocratic régime. In fact, total rejection can only come, in a diverse and competitive forum, from the increasingly consolidated publishing establishment itself when it declines to undertake the publication of a manuscript in the first place. And with the proliferation of small presses and the ascendance of self publishing as viable, if less expeditious or prestigious strategies for writers, even the indifference of mainstream publishers is not always the final word.

It should be mentioned that several book erasures have occurred in US publishing in recent years when a particular volume was deemed censorship-worthy not by the vigilantly value-defensive right but the vigilantly value-defensive left. I remember cases in which books were either summarily withdrawn from planned publication at the eleventh hour or lustily vilified afterward via media furors that erupted on the subject of their authorship—self-righteous squabbles over whether a given author had the “right” to generate the fictional content in question. Such cancellations are a blot on the escutcheon of the left as certainly as cancellations from the right, and the deference of any publisher to them a mark of rank cowardice.

Propagandistically, cancellations from the left are seldom referred to as bans: bans, one argument may go, happen after publication rather than before or during it. Effectively cancellations are bans, however, despite the reluctance of the censorious left to call them by that name (since “banning” is supposed to be the refuge of right-wing scoundrels, right?). They emerge from a similar hysteria of virtue-signaling and result in similar black-listings.

Whatever we call them, and whether they arise from the right or left, campaigns to quash speech are timewasting, truth-wasting exercises in the denial of social reality.

In the wake of leftist cancellations, so-called sensitivity readers have begun to be hired as a mechanism for reassuring a publishing corporation that a piece of writing does not risk the giving of offense to a predetermined set of readers. This paternalistic screening is manifestly also a form of censorship, for censors are censors whether their motivations are noble or base. Censorship is an act, not an intention or feeling.

So is, arguably in softer garb, the trend of trigger warnings, which—mirroring the grim cancer label on a pack of cigarettes—dull the impact of a product or dissuade users entirely by advising them that its consumption may be hazardous to their health. What a trigger warning presumes is that readers are entitled to be protected before the fact from the possibility of powerful emotion, an odd entitlement at best and one that is seldom afforded to any being in the course of the rest of life.

The implication is that art should be a safe space, divested of surprise or shock, into which folk can enter with the polite reassurance that their daily journey through the world will not be substantially disrupted.

This is a direct undermining of the idea of art. The freedom of all speech that is not an incitement to violence or a defamatory or libelous falsehood must be protected as sacred, and the very premise of fiction is that it consists of imagining the lives of others.

Anyone has the “right” to imagine and write anything; anyone has the right to either read it or not read it, enjoy it or not enjoy it, deem it an artistic failure or success; and which categories of others can be imagined by an author should be neither prescribed nor prohibited.

The notion that content should align with an author’s demographic identity is as chilling and stultifying as any other muzzling. Without the freedom to embark on ambitious experiments in negative capability there would be no Moby Dicks or Anna Kareninas—no brilliant or meaningful fiction and in the end, really, no fiction. For fiction that fails to challenge preexisting views and assumptions is nothing more than idle chatter—small talk. And small talk may help to pass the time but doesn’t invest that time with learning or vibrance or novelty.

The social enterprise of the left is rightly the expansion of enfranchisement and equity, and as I write, that agenda is profoundly embattled, both in the United States and in other countries. Yet the solution is not to shame or pillory those artists who dare to drive outside their assigned lanes. Whatever we call them, and whether they arise from the right or left, campaigns to quash speech are timewasting, truth-wasting exercises in the denial of social reality.

In the case of literature, though not freeways, adventurous lane-changing should be encouraged. Not only lane-changing, but crossing the median, driving on the shoulder, careering across fields, crashing through barns and outhouses and toolsheds, even slapping wings on the car so that it soars aloft.

At that point the lines painted on the asphalt turn from cages into features of the landscape among many others, and the mysterious flying object ceases to be easily recognizable. It may be an animal or a spirit or an alien or god—it no longer resembles a car at all.

__________________________________

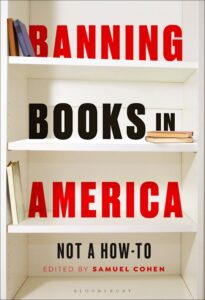

From Banning Books in America: Not a How-To, edited by Samuel Cohen. Copyright © 2026. Available from Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing.

Lydia Millet

Lydia Millet is the author of the novels Sweet Lamb of Heaven, Mermaids in Paradise, Ghost Lights, Magnificence and other books. Her story collection Love in Infant Monkeys was a Pulitzer Prize finalist. Her new novel is A Children's Bible. She lives outside Tucson, Arizona.