What Happens When Gen Z Encounters Catullus’s Filthiest Poem?

“Reading wakes us up to love, culture, grief, war, a range of possibilities too vast to name, and also to great discomfort.”

In this moment of especially rabid book banning, my high school senior has been translating Catullus in her Advanced Track (AT) Latin class. Catullus’s poems disappeared from the Western canon for centuries (likely because medieval Christian scribes avoided copying lurid pagan texts) yet were rediscovered and reprinted in the Renaissance, and are still alive millennia later, when would-be censors are long forgotten.

Catullus’s work shows us ourselves, in all our three-dimensional goodness and terribleness, and sometimes this vision, in 2025, comes as a fun vindication. Take Catullus’ bullying and yet vulnerable poem number 15, in which he admits, “I fear you, Aurelius, and your penis.” Jealous of and threatened by Aurelius, Catullus first euphemizes, entrusting Aurelius with the care of “my boy,” then morphing into the half plea/half threat that anthropomorphizes Aurelius’s penis (imagine the joy in the classroom) should it take advantage: “Because you let it go where it pleases, as it pleases, as much as you wish. When it is out, you are ready.”

My daughter, the lucky student called upon to translate these lines aloud, chatted openly with me after school about whether it would have been too colloquial to describe Aurelius’s penis as “at the ready.” And what it means to run a radish or mullet through someone’s backdoor, the poem’s final threat and incredible landing.

Is there anything so useful and intimate as a conversation with your teenager about scandalous language, vocabulary which any sane parent knows their kid knows, and which, because Catullus has formalized it in lovely hendecasyllables, becomes fodder for frank discussion? Not to mention the twist that in the age of banners pulling Gender Queer and The Bluest Eye off school library shelves, we can freely read the same first century BCE poet who fears Marcus’s penis in one poem and weaponizes his own in the next.

Is there anything so useful and intimate as a conversation with your teenager about scandalous language, vocabulary which any sane parent knows their kid knows, and which, because Catullus has formalized it in lovely hendecasyllables, becomes fodder for frank discussion?

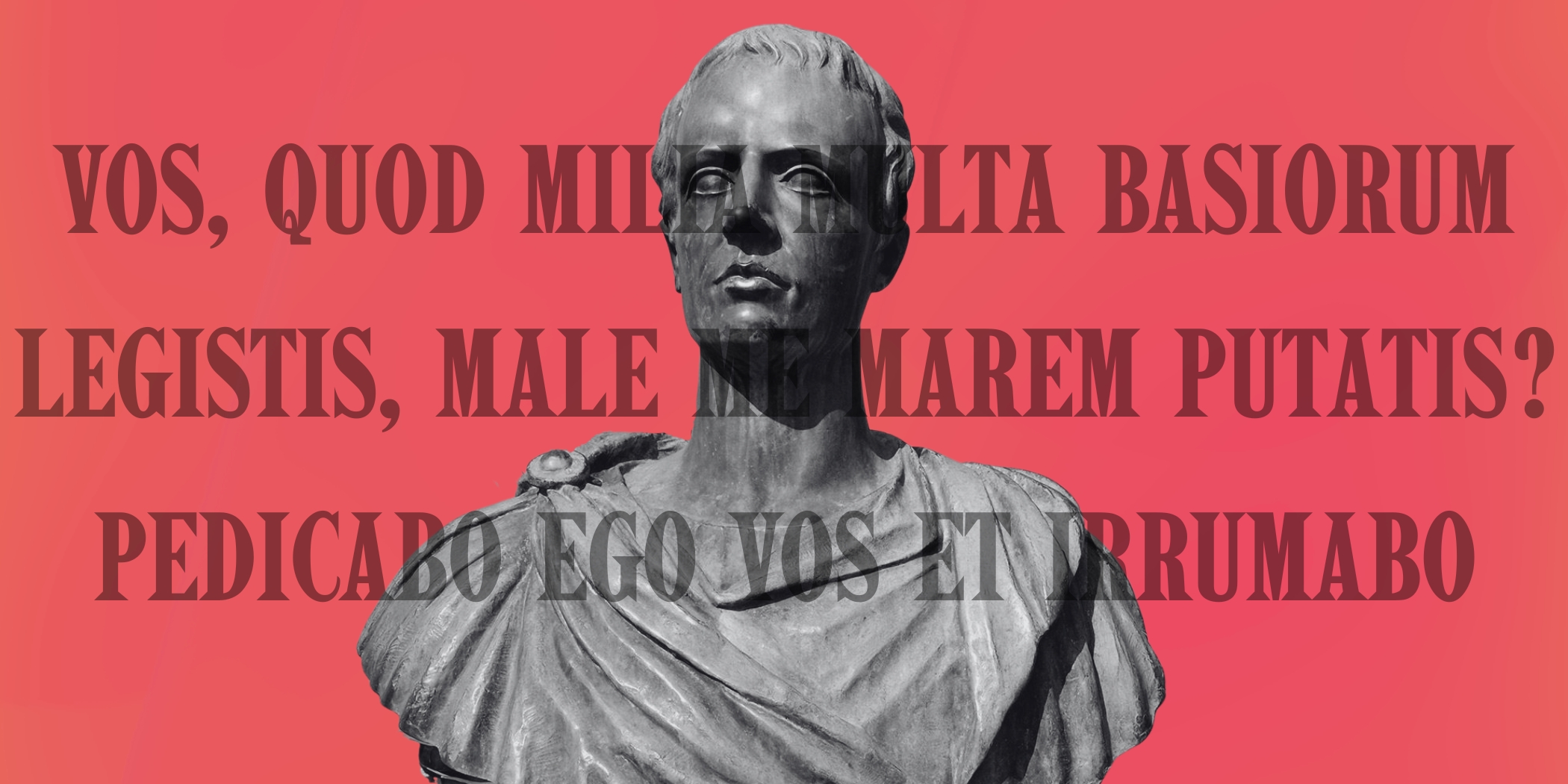

In Poem 16, riled up at being mocked for the softness of his poetry (a hilarious irony, given what the poems say and do), Catullus declares, “Pēdīcābō ego vōs et irrumābō.”—“I will sodomize and face-fuck you.” Her teacher didn’t require it, but offered extra credit for 16, telling the kids, “This one? Well. . . it’s optional,” and then watching them all run into the hallway to begin their translations instantly. And as my daughter observed, after feverishly translating the poem: “There are so few euphemisms in English for face-fuck.”

This was outside the general range of our after school-snack chats, and yet, I’ve always thought kids should have access to the entire range of vocabulary, that part of our job as parents and adults is to let them understand which words to use in what contexts. And how to translate the most precise and expressive of them. So what music to my ears were her astute assessment about the precision of Catullus’s diction across languages and the weirdly contemporary vocabulary itself.

It seems poetic and meaningful that a seventeen-year-old would be grappling with how to make Catullus 16 work in 2025 (She refused the f-slur in favor of calling one of Catullus’s opps “bitch-boy”) while legislatures debate whether the word “penis” can appear in a library. The act of reading what’s contained in Catullus (lust, envy, grief, rage, delight, radical satire, mockery, and finely calibrated obscenity) is one of countless small refusals of the notion that human experience should be banned or censored. Catullus gives us energy and also context.

The pious John Milton, noting that virtue cannot be known without knowledge of its opposite, argued against censorship: “I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered virtue, unexercised and unbreathed, that never sallies out and sees her adversary.”

Cloistered virtue, indeed! How can we know what’s virtuous, gentle and good, without reading, acknowledging, and parsing its opposite? And how can we stand up to corrosive and inhumane forces without naming them? It is an ignorant and unreasoned stance to argue that reading the adversary of virtue will set an example, trigger, or otherwise amplify bad behavior. To admit what hurts, agitates, and offends us in fact illuminates what is complicated and good in us. Catullus openly mocked not only his rivals, but also leaders, generals, and their allies. He hated Caesar’s friend Mamurra, a wealthy, corrupt engineer whose bourgeois degeneracy made him a tempting mark.

The language marks power structures, laying bare the capacity of human beings, both leaders and poets, for contradictory behaviors and motives.

In Poem 29, Catullus asks: “Who can see this, who can stand it. . .” calls Mamurra a shameless glutton and gambler, and Romulus “Sodomite Romulus” on a tear through the beds of throngs of men. Caesar, implicated by the insults hurled at his associates, is mockingly referred to as “the one and only general,” and the leaders accused of looting: “everything the Gauls and the remotest Britons once possessed.” Catullus doubles down on Caesar and Mamurra in Poem 57, in which he calls the pair “twins,” “abominable sodomites,” “fellators,” and “stains” that can never be washed out.

These accusations, like the obscene moments in his poems, showcase the fault lines in Catullus’s society (and ours). The obscenity is not gratuitous, because it peels up would-be censors’ hypocritical impulses to euphemize about what is really happening. The language marks power structures, laying bare the capacity of human beings, both leaders and poets, for contradictory behaviors and motives.

When Catullus writes, “Pēdīcābō ego vōs et irrumābō”,” he is, in a literal sense, naming appetites and humiliations that agents of power and propriety try to hide or erase. Turning the dial down on what is dangerous and enduring in Catullus’s work would destroy its momentum and meaning; does anyone want to argue that we should stop reading him? He has not yet been a casualty of Moms for Liberty or today’s other torch-bearing book banners. Students reading him are not only learning poetry, scansion, translation, and the classics, but also performing a small yet profound resurrection of freedom, one that reaffirms the essential fact that literature is not and was never meant to be safe.

Book banning is a movement against being or feeling alive, seeing with clarity what is already good and what can be made better.

Reading wakes us up to love, culture, grief, war, a range of possibilities too vast to name, and also to great discomfort. Are there scenes, lines, sentences and stories that trigger us, no matter who we are? Of course. But should we avert our eyes from or ban such work?

Catullus’s vast capacity for love and sweetness is made all the more visible by his unflinching view of humankind; we get to measure the distance between what he hates and what he loves. Sometimes, as in 85, “Odi et Amo,” “I hate and love,” they are one and the same. And this is true of all of us. Poem 5 contains thousands upon thousands of kisses for his Lesbia; 51 has her laughter bringing him near death, his first sight of her rendering him voiceless with love.

Book banning is a movement against being or feeling alive, seeing with clarity what is already good and what can be made better. It is truth banning, and while it particularly silences vulnerable people, it also closes possibilities and voices for all of us, narrowing the narrative of our society and obstructing our views of what is essential to see.

This latest wave echoes every other across time, and as usual, it is a failing attempt to create a cloistered virtue. Fueled by a humorless fear of precisely the human experiences and emotions that connect us, book banning ironically often metamorphosizes into acts of promotion, and just as often ends up exposing vile and corrosive hypocrisy in those lighting the matches.

Book banners have had their moments but never conquered basics of human behavior. Catullus lived for only 30 years 2100 years ago, but his poems resonate with clarity today. And teenagers keep scanning and parsing Latin verbs about lust and betrayal, in conversation with one another and a poet who lived before the English language itself.

Like Catullus, they are practicing a version of what the oft-banned James Baldwin describes as the responsibility of writers: confronting what we would rather not know about ourselves, and by doing so, discovering and articulating what it means to be human. There is no better path to being virtuous.

We readers are all connected, sometimes by giddy embarrassment or horrific shock, to everyone who is alive or who has ever been alive. Even as book burners are defunding public libraries, kneecapping schools, and trying to eliminate whatever offends their narrow senses of “appropriateness,” little rebels (AT Latin nerds and their brave teachers) are laughing in Latin across states and centuries.

Rachel DeWoskin

Rachel DeWoskin is the award-winning author of five novels: Someday We Will Fly (Penguin Random House, 2019); Banshee (Dottir Press, 2019); Blind (Penguin Random House, 2015); Big Girl Small (FSG, 2011); Repeat After Me (The Overlook Press, 2009); the memoir Foreign Babes in Beijing (WW Norton, 2005), and two poetry collections, Two Menus (University of Chicago Press, 2020), and absolute animal (University of Chicago Press, 2023). Her awards include a National Jewish Book Award, a Sydney Taylor Book Award, an American Library Association's Alex Award, and an Academy of American Poets Award, among others. Three of her books, Foreign Babes in Beijing, Someday We Will Fly, and Banshee, are being developed for feature film or television. DeWoskin's poems, essays, and articles have appeared in journals and anthologies including The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, The Baffler, Ploughshares, and New Voices from the Academy of American Poets. She serves on the national steering committee of Writers for Democratic Action (WDA). Visit her at www.racheldewoskin.com