What Happens in a Pandemic When Your Friendship Superpower is Cooking?

Chef Lisa Donovan on Finding Ways to Nourish the Ones She Loves

The day I find out two of my closest friends are getting a divorce, I make plans to see one of them at the end of the week.

We’ll be careful.

We’ll sit on opposite sides of my porch.

I have not seen a friend in two months.

I quit drinking for a spell, deciding quarantine and my depression were already at odds with one another—they did not need a compatriot as irreverent and as careless and as mean as alcohol in their midst. My most familiar coping mechanism to fall back on was gone. And, so, down the rabbit hole I went.

I had exactly four days to tame a thing that I hadn’t realized had become so overgrown—tough tendrils of isolation protecting the very young growth of a new kind of rediscovery that I would not, could not, exit quarantine without honoring and embracing. I was covered up. I had, after all, spent 42 years toughening and softening in just the right measures—but always for the world’s needs, not my own. How to mother, how to daughter, how to career, how to wife, how to friend—the work that women so often do, building their whole lives around industrious love.

The other side of endless giving is sometimes frustration and emptiness. A human can be simultaneously grateful for the life she’s built, and quite lost within the borders she has created to keep that life together.

Sometimes my whole life feels like one big hunger pang.

As Friday drew nearer, the voices in my head got louder and louder, all the reasons I was not the friend anyone needed in a crisis. I shamefully cancel three hours before my friend is supposed to arrive. I blame work. I blame deadlines. I did not know how to do this pillar of strength shit quite the way I used to. I could not even muster an honest try.

She responds to my overreaching excuses with a heartbreakingly disappointed and deserved, “sure.” I drive an hour out of Nashville to a farm to pick up gallons of strawberries, and slink by her apartment to leave some at her doorstep, trying to remember that I still know how to feed people at least, maybe.

But they are only guilt strawberries. They are incompetence strawberries. They are bright red, straight from a farmer, picked that morning. They are juicy and still warm from the sun.

I am certain that they taste only and entirely of my inadequacy.

On Monday, I knew what I had to do. I texted, “I’m making you soup.”

This was not guilt soup. This was not inadequacy soup.

During this Broken Time, I find that I grab ginger a lot. I cling to it in my kitchen like a talisman in each of my increasingly out of body soup moments. As I begin to make the first soup, I think about what ginger does for a body, its dedication to the gut, its taming properties. I smell the hunk I hold in my hand and I think about my hunger. I have been trying to curb my hunger my whole life. I go through this world, full of desire and longing, carrying all of my interrupted dreams in an overflowing pocket. Hunger is the thing I can’t bear the most about myself any longer. Sometimes my whole life feels like one big hunger pang.

So. Ginger.

I have a bag of mixed greens sitting in my fridge from a farm pick-up last Tuesday.

I fill my sink with ice cold water and plunge in the greens, using my hand like a washing machine paddle. Greens have a way of clinging to the earth from which they came, little bugs every once in a while making an appearance during the process. I only find one that day, an unattractive stink bug splashing and floundering in the murky water. I gently scoop him in my hand with some water so that maybe he won’t know the difference between me and the sink and take him outside. I think of W.S. Merwin. I think about a poet’s hands and a baker’s hands and how similar they are, making nourishing things out of the basic elements, dealing in fundamentals at every moment in their life, taking either language and truth or water and flour and building whole worlds around them, worlds where people can survive, maybe even thrive. And I try to remember the words. How did it go?

I stop to look it up.

I will take with me the emptiness of my hands

What you do not have you find everywhere

Yes.

I wash the greens a fifth time.

I start to chop and realize I’ve gotten ahead of myself, prepped in the wrong order. The large chunk of my brain (and identity) that still believes it’s a chef even though it is no longer and hasn’t been for a long time, recoils at my stupidity, my lack of planning, jumping in before thinking the whole thing through. No mise en place in sight. Rookie moves. Economy of motion and prep lists are important, essential. I haven’t written a prep sheet in a couple of years. I have an ache but move past it. I think, “who fucking cares, jesus Lisa.” I take a deep breath and remind myself that my life in a kitchen is simpler now, and that this is what I wanted, eventually, I learned to want it this way anyway, and it is, by and large, a very good thing. I have to remind myself of that a lot. I miss professional cooking like I miss smoking. I know it will kill me, but christ if it didn’t feel good while I was doing it. Even remembering feels so good. I let myself have one seductive memory, like a cigarette.

I stop chopping. From my freezer, I pull out a frozen chicken carcass stored in a bag with onion and garlic and celery and carrot and herb trimmings from various other meals, plop it into a stock pot, cover it with water, high boil then low boil. I want the goodness from the roasted bones, I want whatever I can get of the marrow. This soup will be medicine.

I grate the entire knob of ginger into the bowl with the garlic. It smells almost right. It could boil like this all day and through the night. It actually should. But I am impatient.

Coconut oil. Make it warm. Add the ginger and garlic. You can’t rush garlic. Or stock. But especially garlic. You will make it bitter. You will make it tough. Give it time. Time is all we have in these days. So, take it. Take it all. Turn all your burners on low for once in your life. Good soup takes time. It never takes a long time. But it takes some. And giving it the exact time it requires is just the thing.

This is where you can add your flavor, your spices, your medicine—this is where you add you. The whole soup is you. But this is where you can really decide what the day requires. This is where you can remember how to be a good friend. This is the part. You can reach for the turmeric. This is where you put your favorite, familiar ground cumin. This is where you can pull the chile negro that you ground by hand in New Mexico near where your grandmother was born, the closest you have ever felt to her, and you can give that to your friend. You can toast it with the ginger and the garlic and coconut oil and the turmeric and you can inhale deeply to maybe get close to that feeling again and you can cry a little into the pot because maybe your tears can ease something, maybe those kind of tears are medicine too.

I cannot smother my friend with my body. I will smother her with greens.

I add more oil because I know my friend. I know she will make food her last priority. I know she has hunger too, deep ones like I do. Overfeeding them is my habit. Starving them is hers. We have been pushing and pulling on our hunger together for years. I know she will be too thin. I know she will need this fat. I know this will be the thing I can give her the best because it is the thing I give her even when I’m not preparing her food. I am the promise of more. She is the promise of less. We are each other’s balance. And I know my job. I pour more oil in until the garlic and ginger and spices are floating.

I add more greens. More greens than the pot can handle. I cannot smother my friend with my body. I will smother her with greens. I hope she feels their weight. I hope they sit in her hips and on her chest and rest like a hand on her back, or even on her face, when she is alone. I bid them to be more than vegetable today.

I salt. I salt and salt and salt. I bring life to the things in the pot, that is what salt does. It takes all of your good intentions and brings them to life.

While the soup cools, I make a prep sheet for the week. Tuesday will be fish curry with coconut milk broth, like a Tom Kha as best as a white girl can do it. And then come Wednesday, a heartier lentil soup. Everything is “we.” I am making this soup for the both of us. We will eat it in each of our separate places, but together in the strange pain, the new understandings and the safety of our individual isolation.

We can eat. We can heal. These are broken times, but we have soup.

__________________________________

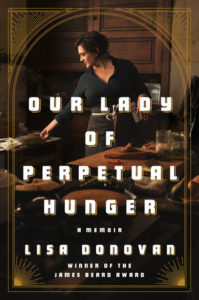

Our Lady of Perpetual Hunger by Lisa Donovan is available via Penguin Press.

Lisa Donovan

Lisa Donovan has redefined what it means to be a “southern baker” as the pastry chef to some of the South’s most influential chefs, including Margot McCormack, Tandy Wilson, and Sean Brock. Unabashedly serving her church cakes and pies to finish fine-dining experiences, she has been formative in establishing a technique-driven and historically rich narrative of southern pastry. Donovan received a James Beard Award for her writing in Food & Wine, where she is a regular contributor, and she has been a featured speaker at René Redzepi’s globally renowned MAD Symposium. Our Lady of Perpetual Hunger is her first book.