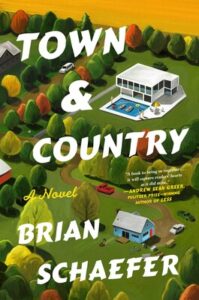

What Happened to My Political Novel When I Resisted Satire and Leaned Into Idealism

How Brian Schaefer‘s Town & Country Went From Snarky to Sincere

When I started writing the novel that became Town & Country, I imagined it as a sharp critique of urbanites flooding a trendy rural swing district, intending to skewer the obliviousness of a group of wealthy gay men and their impact on local politics. But six years later, it arrives on Election Day as something else entirely: a heartfelt political novel that resists cynicism in favor of empathy.

Getting there required frank feedback from a trusted early reader about my natural voice, an embrace of the sincerity that I’d suppressed in my writing for fear of coming across as too idealistic, and some deep reflection on what I wanted my work to offer.

Satire slyly distorts the politics of the day in unexpected and amusing ways to somehow make us see them more clearly.

When I chose to structure Town & Country around a congressional race, my initial impulse was to approach it as satire—to my mind, literature’s most mischievous and delightful genre—because the situation felt ripe for ridicule and because that mode would add a comfortable distance (and, I hoped, a layer of smart skepticism) between me and the story.

There’s a long, delicious history of political satire in literature, dating at least to Aristophanes’s famous sex strike and continuing through the wacky Floridians of Carl Hiaasen, by way of Jonathan Swift’s Yahoos, George Orwell’s manipulative barn animals, Muriel Spark’s Machiavellian nuns, and Paul Beatty’s outrageous Supreme Court case, among many, many others.

Satire slyly distorts the politics of the day in unexpected and amusing ways to somehow make us see them more clearly. Using irony, exaggeration and humor (among other tools), it can make the powerful appear pathetic, the sinister seem stupid, and can render a scary world merely ridiculous, and thus more manageable.

So as I set to work on my novel, I aspired to join the lineage of the devilishly witty writers who seeded deep social truths in the heart of their travesties. But I soon found that it wasn’t working for me. Or rather, my husband helped me see it.

Finally, during a big debrief, he gave it to me straight: “You’re not a satirist. It’s just not your mode of processing the world, and it’s not serving the story.”

He was my first reader, the first person I entrusted with the disheveled prose and budding ideas, and the first person to hear the voice of the book, which he found inconsistent. He’d indicate a rowdy ensemble scene meant to highlight some social paradox and flag it as false or forced. Then he’d point to a poignant moment of insight and say, this feels more like you. Finally, during a big debrief, he gave it to me straight: You’re not a satirist. It’s just not your mode of processing the world, and it’s not serving the story.

Accepting that diagnosis took time. I refused to let go of the idea of my novel as a bravura performance of political cynicism that flattered the reader’s own. It was just a matter of craft, I told myself. If I could master satire’s ingredients, I was sure I could pull it off.

But as I revisited my husband’s critiques, examined the parts he preferred, and considered why those emotionally honest moments were more successful, I began to ask myself what I really wanted to convey through this story, and through my writing in general.

We don’t need more mockery; we need to heal the way we relate to each other.

I came to understand that satire was actually working against my intention. Satire is brilliant for exposing the folly of humans, especially those in power and those working in bad faith—the hypocrites and the frauds—and can be particularly potent when set in irrational or dystopic times. Hyperbole feels right at home in a burning world.

Yet when I looked around at our broken politics and the toxicity of our civic discourse today, it seemed clear that times are dark enough and there are plenty of fools in the daily news already. What’s gained by indulging our doom? I decided I didn’t want to add to or illustrate the panic. We don’t need more mockery; we need to heal the way we relate to each other.

In my writing, it felt more subversive—radical, even—to imagine a better version of our society rather than magnify and embellish the worst. Suddenly, sincerity felt like a fresher approach to a contemporary political story—more interesting, more unexpected, and more aligned with my artistic ethos.

When I started to look beyond satire for inspiration, I saw writers engaging with politics in a wide range of modes that better fit my temperament and worldview, even if in vastly different styles: Richard Russo’s funny communal portraits, Laura Esquivel’s fantastical social critiques, Marilynne Robinson’s self-described cosmic realism, or George Saunders’ emotionally grounded surrealism.

Still, eschewing satire felt risky. As my drafts prioritized emotional arcs over flamboyant antics, I worried that the story was giving too much Obama-era optimism, not enough Trump-era despair, and that it would feel so disconnected from the current moment as to be embarrassingly naïve.

But I leaned into the idealism and embraced the gulf between fiction and reality—much like what satire does, but in the tonally opposite direction. I stripped my novel of any mention of political parties (the words “Democrat” and “Republican” never appear) to free readers from automatic associations; fictionalized the town and placed it in an unnamed state; then set the story in an undefined year so there would be no national figures or specific election cycle to reference, allowing the story to be solely about these people in this place.

Rather than rob the story of its teeth, this enabled me to explore the pain, loneliness and personal demons of my characters with sympathy rather than stinging bite.

The surprising result was that Town & Country took on a fable-like quality—by which I mean its version of American politics became almost implausibly decent (not that it became populated by talking animals, though that would have been a nice nod to Orwell).

Rather than rob the story of its teeth, this enabled me to explore the pain, loneliness and personal demons of my characters with sympathy rather than stinging bite. And it allowed me to offer a vision of society that I think most people aspire to, rather than one we fear.

Ironically, some early reviews of my work—positive ones—have referred to Town & Country as a satire. I think it comes from the expectations that political novels, especially those told with some levity, must be making fun of the system and the people participating in it. The fact that my book, in part, tracks the lives of the affluent probably adds to that perception.

I wondered whether to embrace this label but ultimately felt it was a misdirect of what the book is trying to do and where it lands. Town & Country takes its characters and their struggles at face value and, despite some gentle needling, celebrates their genuine camaraderie and familial commitment.

But I admit to being tickled that people still catch a whiff of satire in the book, which I take to mean that they find something enjoyably heightened in the characters and scenario. Yet writing my first novel helped me understand it’s not my modus operandi. While satire may expose our absurdities, sincerity honors our humanity—and that’s the story I want to tell.

__________________________________

Town & Country by Brian Schaefer is available from Atria Books, an imprint of Simon and Schuster.

Brian Schaefer

Brian Schaefer contributes regularly to The New York Times and has written for The New Yorker, New York magazine, and more. His debut novel, Town & Country, is forthcoming from Simon & Schuster in November.