What Growing Up On Mars Would Do to the Human Body

And Yes, You Can Have Sex in Space

The annual SXSW conference in Austin, Texas, can be a bit overwhelming. What started as a fairly modest four-day music festival in 1987, drawing some 700 attendees, has become a ten-day extravaganza of panel presentations featuring celebrities and business leaders, film screenings, technology showcases, and—yes—music. These days hundreds of thousands of people converge on downtown Austin for “South By,” as it’s called by those in the know. When I was a graduate student at the University of Texas in the early 2000s, I always avoided the festival and its inevitable crowds, which was relatively easy to do since it tended to be held the same week as the university’s Spring Break.

But when I received an invitation in 2023 to attend a SXSW panel presentation with the title “Sex in Space: Sex and Reproduction Beyond Earth,” I knew I had to go. After all, any plans to create a permanent settlement on Mars or elsewhere in space wouldn’t last long if we can’t have kids there.

The invitation came from a Dutch entrepreneur named Egbert Edelbroek, who would be one of the panelists. I had first met Edelbroek in Houston in 2019, two years after he founded a company called Space-Born United. At the time, he was in the early stages of fundraising for an ambitious goal: to pioneer human reproduction in space. Edelbroek came across as a polished and professional businessman, young and good looking, with a big smile and warm personality. He had a PhD in corporate courage development, which seemed appropriate for the bold project he was now pursuing. He told me that the idea for the company had come about after he had become a sperm donor. He was curious about the various ways that donated sperm can be utilized, and he began to learn about assisted reproductive technologies such as in vitro fertilization, or IVF. As a lifelong space enthusiast, who as a child had recurring dreams about being on another planet, Edelbroek wondered if IVF and the subsequent stages of embryo development were possible beyond Earth.

As is true anywhere, human reproduction in the cosmos will depend on more than just the act of sexual intercourse.

Now, four years after our initial meeting, I was eager to find out what SpaceBorn United had accomplished, so I made the two-and-a-half-hour drive to Austin. The downtown streets were filled with people wearing large, colorful SXSW festival passes dangling from lanyards around their necks. Edelbroek met me at the registration area in the Austin Convention Center. He introduced me to Alexander Layendecker, one of the other panelists and an advisor for SpaceBorn United. A helicopter pilot in the US Air Force Reserve, Layendecker earned a master’s and a doctorate from the Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Sexuality. We walked down the hall where we met the other two panelists.

Simon Dubé was a postdoctoral researcher at Indiana University’s Kinsey Institute where he was studying human sexuality with a focus on “human-machine erotic interaction.” The fourth panelist was Shawna Pandya, a Canadian emergency room physician with a focus on extreme environments and a real passion for space. Indeed, Pandya seemed to be everywhere in the worlds of space medicine and space science. I had met her briefly at NASA’s Human Research Program Investigators Workshop in Galveston a few months earlier, and her name popped up as a speaker at almost every other space-related conference or event I learned about or attended. This was shaping up to be an intriguing presentation.

After a quick lunch we walked a few blocks to the JW Marriott hotel where the panel would be held. I accompanied Edelbroek and the other panelists to the green room to prepare. While Dubé, Layendecker, and Pandya sat casually chatting around a table, I noticed Edelbroek was sitting by himself in the corner of the room practicing his presentation. He seemed nervous. This was a high profile public event and a big opportunity to share what his company was doing. Soon, a woman with a headset appeared and told us it was time to head to the stage. She escorted us down a back staircase, through a service hallway, and into a room filled with people.

Layendecker appeared first on stage and introduced himself as a sex researcher and astrosexologist. He then introduced his fellow panelists one at a time. Upon taking the stage, Shawna Pandya thanked him and added, “I hope we have an uplifting discussion with a happy ending.”

Clearly this was not going to be a dry, academic presentation.

Each of the panelists said a few words about why research on sex and reproduction in space is important. Pandya argued that research on human reproduction in space not only is essential for our long-term survival, but is also a short-term need. Space tourism is on the rise, and with the expected development of space hotels in low Earth orbit, she pointed out that understanding the consequences of a human baby conceived in space has become critically important. “We know what people do in hotels,” she quipped.

The conversation shifted toward a discussion of whether anyone had already had sex in space. The official answer from government space agencies like NASA was that no one has—but that hasn’t stopped the speculation. The people perhaps most likely to have completed what Pandya called “the first human docking maneuver in orbit” are Mark Lee and Jan Davis. In 1992, they spent eight days together on the Space Shuttle Endeavour as newlyweds. NASA didn’t typically assign couples to the same mission, but Lee and Davis kept their marriage a secret until shortly before the launch, allowing them to be the first couple to spend their honeymoon in space. Afterward they declined to answer any questions about what, if any, private interactions they had while in orbit, and NASA certainly would not entertain any suggestions that their astronauts did anything “unprofessional.”

Some speculation has existed about whether the basic physiological processes necessary for intercourse, particularly for men, might be compromised by microgravity. But NASA astronaut Mike Mullane put this concern to rest in his 2006 memoir, Riding Rockets. “To my surprise, I did not wake up alone,” he wrote. “My closest friend was alert and waiting. I had an erection so intense it was painful. I could have drilled through kryptonite. I would ultimately count fifteen space wake-ups in my three shuttle missions, and on most of these and many times during the sleep periods my wooden puppet friend would be there to greet me.”

So much for that potential problem.

What about for women? No reports of female astronauts have yet included any description of how their time in microgravity affected their libido or sexual response. But, as is true anywhere, human reproduction in the cosmos will depend on more than just the act of sexual intercourse. Another concern is how the gametes, or the reproductive cells, might be affected by conditions beyond Earth.

A 2022 paper by Stefan du Plessis and colleagues reviewed all the available scientific literature on the topic of how space conditions affect sperm motility and other factors related to male fertility. They found a total of twenty-one relevant articles that used a variety of techniques to assess the effects of microgravity and/or radiation on sperm—though only one study examined the combined effects of both microgravity and radiation. Only four of the experiments were conducted in space. Four of the studies involved human sperm—none of which were conducted in space—with the remainder involving animal research subjects. The authors concluded that the limited amount of available evidence makes it difficult to conclude whether spaceflight has a positive, negative, or neutral impact on the movement abilities of sperm. However, they did find evidence that sperm production decreases when exposed to microgravity and radiation. What’s more, radiation exposure can cause harmful mutations to the DNA in sperm—mutations that have the potential to be passed on to subsequent generations.

Given how much biomedical research has been conducted in space, the scarcity of research on reproduction surprised me. Indeed, a report released in 2023 by the US National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine pointed this out, concluding that our understanding of how space affects reproduction is “vital to long-term space exploration, but largely unexplored to date.”

Addressing the other panelists at the SXSW event, Alexander Layendecker asked why so little research has been done on sex and reproduction in space. Shawna Pandya pointed out that there have in fact been reproductive studies on a wide range of animal models, including rodents, jellyfish, quail, sea urchins, and fish. But the data, she noted, were conflicting.

Layendecker agreed, pointing out that NASA has historically discouraged its employees from publicly discussing the topics of sex and human reproduction in space. He cited the example of Yvonne Clearwater, who led NASA’s habitability research group in the 1980s. While working on designs for space habitats, she advocated for including sleeping spaces with privacy and soundproofing.

“If we lock people up for 90-day periods, we must plan for the possibility of intimate behavior,” Clearwater wrote in a 1985 article for Psychology Today. The backlash was severe, Layendecker said. Media headlines implied that taxpayer dollars were being frivolously spent on promoting sex in space, prompting NASA to have to assign someone to reassure Congress that this was not the case. According to Layendecker, Clearwater was subsequently forced by NASA to publicly state that no work was being conducted to promote or encourage sexual activity among astronauts. “So politically, [sex] has always been a very explosive topic in NASA,” Layendecker concluded.

“Fortunately, they realize that,” added Egbert Edelbroek, noting that NASA officials recognize that the political climate limits the agency’s ability to fund and support research on sex and human reproduction. “And they explicitly encourage focused biotech companies like Space-Born United to address this challenge,” he said. Edelbroek suggested that to advance our understanding of human reproduction beyond Earth, it would be helpful to separate sex from reproduction. That way, he argued, each stage in the process of human reproduction can be carefully studied to determine how they are affected by the conditions in space.

“For the next five to ten years we will focus on the very first stage of reproduction: conception and the first five to six days of embryo development,” Edelbroek said. He stood up and walked over to a table next to the platform where the panelists were sitting and removed a white tablecloth to reveal what looked like a UFO. It was a disc-shaped object, mostly white with a black ring around its wide base. It tapered slightly toward its flat top, giving it the appearance of a flying saucer.

“This is where the actual magic is going to happen,” Edelbroek announced. The object was a full-sized replica of the space capsule that will house a miniature IVF lab. A disc inside the mini lab can be rotated at various speeds to produce artificial gravity to replicate conditions on the Moon or Mars, he explained. Using microfluidics, a chamber containing sperm can be connected to a chamber containing an egg to allow fertilization.

“This capsule has return capabilities. It has a heat shield and a parachute system. It can bring five-day old embryos back to Earth,” Edelbroek said.

Under normal conditions, a fertilized egg will begin to divide after about twelve to thirty-six hours. After another fifteen hours or so, each of the resulting cells will divide again, such that now there are four cells. The divisions continue, with the total number of cells in the embryo doubling each time. These early cell divisions occur so rapidly that the cells don’t have time to grow before they split. That means that the size of the cells decreases with each round of divisions. After seven rounds the embryo consists of a ball of 128 tiny cells with a hollow space in the center. Subsequent divisions lead to multiple layers of cells, which begin to differentiate into those that will eventually form the fetus and those that will form other structures, like the placenta and umbilical cord.

During these early stages of development, the embryo is normally moving through the Fallopian tube. After about five to six days it reaches the uterus, where it implants and completes its development. By this time the embryo has reached the hollow ball stage, called a blastocyst. During typical IVF, an egg is fertilized with sperm in a culture dish where it is allowed to develop into a blastocyst. The embryo can then be frozen until it is time to introduce it to the uterus. SpaceBorn United plans to allow fertilization and blastocyst formation to occur for about twenty embryos at a time in a three-dimensional growth medium while the device is in space, after which the embryos will be frozen. As Edelbroek explained to the SXSW audience, freezing the embryos will pause their development and protect them during their return to Earth.

“We need to protect them and we do that by cryogenically freezing them in exactly the same way that it’s being done on an everyday basis in IVF clinics to safely bring them back to the IVF clinic to study their health,” he said. “We have our first prototype finished and it’s going to go on board a rocket this year within six months.”

The crowd burst into applause and, for the first time since the panel presentation began, Edelbroek smiled.

*

Other questions about human reproduction beyond Earth have to do with what happens after birth. How would a child’s growth and development be affected by life in a space settlement? It is worth noting that essentially all of the information we have about how the conditions of space, like lower gravity and higher radiation, affect the body come from studies of adults. So while we do not have any data, we can at least consider what aspects of child development could be affected by the conditions kids would experience growing up on Mars.

Consider the skeleton. As children grow, their bones obviously get larger. But while some aspects of bone growth in children are determined by our genes, bone growth is also affected by how much force the bones experience. Bone tissue is constantly being replaced. Cells called osteoblasts form new bone tissue, while other cells called osteoclasts break down old bone tissue. Our bones grow when the work of the osteoblasts is greater than that of the osteoclasts. That happens throughout embryo development and childhood, and typically reaches a steady balance at some point during adolescence. But just how much bone tissue gets made depends on how hard those osteoblasts have to work during key times in a child’s development. This is one of the reasons why running around and playing is such an important aspect of a healthy childhood—kids who are more active build stronger bones.

So, would growing up with one-third gravity mean that children on Mars would develop weaker bones? Quite likely. A sad but clear illustration of perhaps the closest situation we have to kids growing up in partial gravity is children who have been paralyzed or have severely limited capability for movement since birth, like some people with cerebral palsy. Given that bed rest studies have been used to simulate the effects of microgravity, people born with cerebral palsy can give us some sense of how a child’s body might be affected by partial gravity. While their bodies still experience gravity, being unable to walk or, in some cases, even move their lower body reduces the amount of force imposed on their bones, especially the bones in the limbs and back. Studies of children and adults who have had this condition since birth show that they have greatly reduced bone density.

If children who grew up on Mars develop weaker bones, would they be able to come to Earth? Earth’s gravity would make them feel about three times heavier, and the g-forces of takeoff and entry would subject them to ever higher forces. They would likely be prone to bone fractures, particularly of bones that support our weight, like the spine and hip. Indeed, studies of people who have been paralyzed since birth show that they are at higher risk for fractures.

Another factor is the heart and other components of the cardiovascular system. Like all muscles, the strength of the heart is due in part to how hard it has to work. Heart muscles atrophy, or weaken from disuse, in adults who spend prolonged times in the weightlessness of space. It takes less force to pump blood all over the body when you don’t have to work against gravity. Children might develop weaker hearts if their bodies develop in partial gravity. That could pose yet another challenge for Martian-born people traveling to Earth.

Lastly, there’s the human body’s largest organ—the skin. We don’t often think about our skin as an organ, but it is. Anthropologist Nina Jablonski has studied human skin, its evolution, and what it does for us. “Our skin mediates the most important transactions in our lives,” she wrote in Skin: A Natural History. “Skin is key to our biology, our sensory experiences, our information gathering, and our relationships with others.”

Would people who had never been to Earth, and perhaps never even met a person who had been to Earth, still consider Earth their home?

People in a Martian settlement would always be either indoors, underground, or in a spacesuit if they go outside. Some aspects of our skin adjust to our environment. Our sweat glands produce moisture to cool us down when we get hot. Tiny muscles connected to our hair follicles contract when we get cold, giving us goosebumps. Cells called melanocytes produce the pigment eumelanin in response to sunlight, which makes the skin darker and better protected from the damaging effects of ultraviolet light. How would a person whose skin had never touched the outside air or been exposed to sunlight or temperature extremes react upon experiencing these for the first time?

These are just a few of the unanswered questions about how children would be affected by growing up on Mars. Others include the social development of kids in a Martian settlement. What would a Martian childhood be like? Robert Zubrin, who has thought more about settling Mars than perhaps anyone alive today, thinks that Martian children would have to work a lot more than most kids do on Earth these days. In his book The New World on Mars, Zubrin wrote that “both the Martian labor shortage and the generally more serious nature of the realities of life on Mars will require that kids grow up faster.” He imagines that formal education would be less emphasized than it is in most modern societies. “My guess is that, starting with elementary school, school hours on Mars will only be about half as long as is typical on Earth, with students spending half their day working and associating with adults at home, in the greenhouse, in the shop, and in the lab—getting a good hands-on education in the process,” he wrote.

One interesting question is how children born and raised on Mars would view their relationship to Earth and its inhabitants. Interestingly, even people who leave Earth for relatively short amounts of time sometimes return with a changed perspective. Veteran astronaut Peggy Whitson talked about this in her speech at Rice University’s graduation ceremony in May 2024. She was standing in the same spot where, sixty-two years earlier, President Kennedy made his case for sending the first humans to the Moon. Whitson told the graduates seated before her about how she grew up on a farm in Iowa but dreamed of somehow going to space someday. After retiring from NASA in 2018 as the nation’s most experienced astronaut, she was hired by Axiom Space as the Director of Human Spaceflight and began serving as a commander for private missions to the International Space Station—the first woman to do so.

In her remarks to the graduates, Whitson reflected on how pushing herself out of her comfort zone changed her perspective on the world—and, more specifically, on what she considered her home. “Early on, my world was family and the farm,” she said. “Later that world expanded a bit to include my local school and then college. But home was still the farm. After I came to graduate school here at Rice, in an entirely different state, home became Iowa. Then I took on a job at NASA where I frequently traveled to Russia and home became the United States of America. So maybe it should not have been surprising that when I went into space, home became planet Earth.”

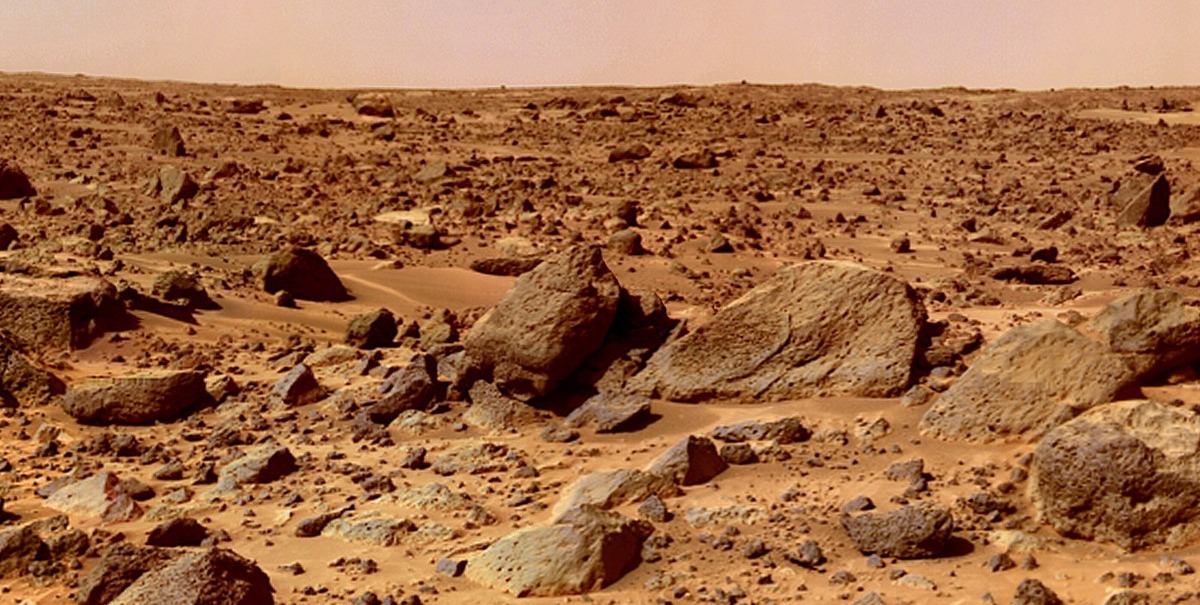

It makes sense that people who have lived their entire lives on Earth would, upon leaving it, look back at the planet and consider it their home. The first settlers on Mars may still consider their true home to be Earth, even as they make the transition to life in their new home on the Red Planet. But what about the first generation of people born on Mars?

Immigrants to new nations often retain ties to their previous countries. The ties can be legal, if they remain citizens of their former nation. But often the stronger ties are cultural, including the language, food, and customs. These cultural identities can extend to the immigrants’ children and grandchildren, but they tend to become a little weaker with each generation. My great-grandparents on my father’s side immigrated to the United States from Greece and Russia. After four generations, my siblings, cousins, and I have retained only a little of the cultural identities that were so important to that first generation of immigrants.

Would the same be true of the fourth generation born and raised on Mars? Would people who had never been to Earth, and perhaps never even met a person who had been to Earth, still consider Earth their home? This seems doubtful. I think it is much more likely that they would consider themselves to be something different—they would be Martian.

__________________________________

This extract is from Becoming Martian: How Living in Space Will Change Our Bodies and Minds by Scott Solomon. Copyright © 2026. Published on February 17, 2026 by the MIT Press. Reproduced with permission from the publisher.

Scott Solomon

Scott Solomon is Teaching Professor at Rice University in Houston. He is also a Research Associate at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History. He is the author of Future Humans, named a 2017 Best Book by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). He is also the host of the podcast Wild World with Scott Solomon and cowriter and coproducer of the series Becoming Martian.