“You gonna plan golf courses out west?”

Today, Chandler has grown into a techie paradise. Condominiums have popped up in unexpected places, vacant lots have turned into mural sites and community gardens. Phoenix’s cultural “scenes” have developed in a way that mirrors places like Austin or Portland. My memories of iterative beige cul-de-sacs, primary-colored shopping centers, and palm trees rising up from neighborhood arterials now feel dated. Phoenix is an urban area, with a new population of young people and progressives, at least in name.

Phoenix’s recently resigned Mayor Greg Stanton (he’s considering a congressional run)—along with many other local politicians—is working to better provide environmental amenities, expand heat shelters, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and better manage resources. Phoenix has guiding documents related to energy efficiency, climate resiliency, the expansion of its urban tree canopy, and waste reduction. At the local level, the cities of Chandler, Tempe, Mesa, Scottsdale, Glendale, and Phoenix itself all have dedicated public servants interested in making their cities more equitable and sustainable, continually seeking grants to plant trees, to retrofit street lights, and conserve water. But it is unclear to me whether these will amount to enough, given the narratives of progress and freedom defining Phoenician development.

I spent a significant amount of my undergraduate years at Arizona State University’s Wrigley Institute. Wind turbines affixed to the front of the building and metabolic statistics about the university’s energy usage greets you as you enter. My former supervisor, Anne Reichman, who I worked for throughout my undergraduate years, runs the Sustainable Cities Network, a university-run center that builds capacity for the Valley’s initiatives in the areas of green infrastructure, solar, and water resources. We catch up in her office, which is similar to how I remember it, covered in cheerful notes and posters of Arizona’s plant life.

The Sustainable Cities Network has launched “Project Cities,” a collaboration between municipal governments and university students to foster collaboration on green infrastructure, resilience, and resource use and energy efficiency. Conversations about regional tree and shade have been reinvigorated. Many of Phoenix’s institutions are composed of individuals attempting to change attitudes about outward growth and excess. Such a culture means that as individuals leave positions in city government or policymaking roles, it becomes difficult to achieve a continuity in these efforts.

“Arizona does everything voluntarily,” Reichman notes. We talk about a culture where progress is “organic” and dependent on the priorities of city managers. She describes how discussing poverty can make policymakers uncomfortable. Progress is difficult, especially for smaller municipalities in the Valley; though Phoenix has resources and the political will to address some of these problems, communities with smaller populations are often without resources or individuals in formal roles to address these issues. Instead they rely on the passion of individual public sector workers to aspire to an ideal of sustainability. A network of progressive nonprofits, municipal workers, and university professionals have worked to make change.

Despite its achievements in water conservation and an increasingly deliberate approach to environmental planning, Phoenix’s love of excess remains. The mall I worked at as a teenager used to feature elaborate fountain shows, set to light and music, a mini version of Las Vegas’ Bellagio Fountain. Families would pass the spectacle, the youngest throwing pennies in the water for good luck. Despite the energy the city saves from its lighting retrofits, many Phoenicians can’t afford to pay for adequate cooling during summers.

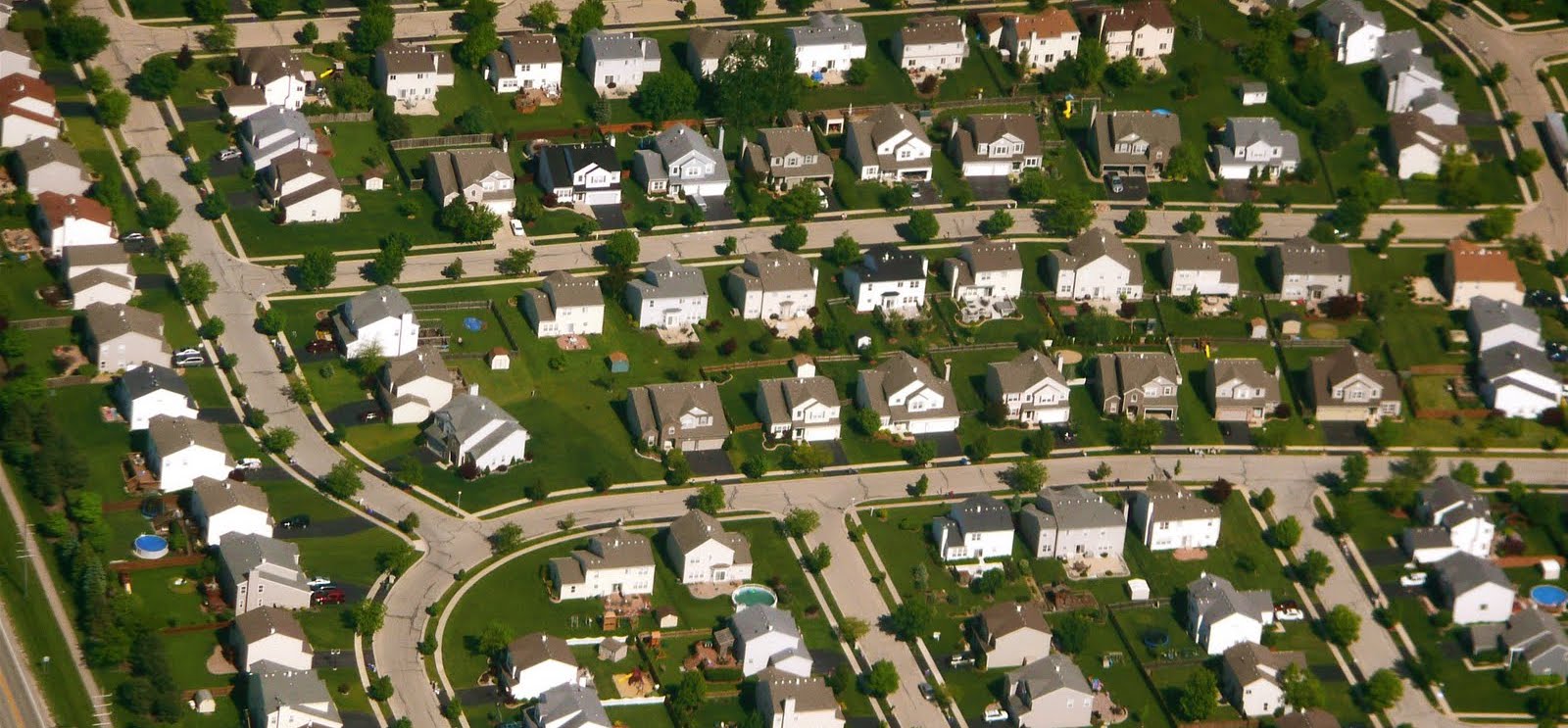

Last winter, I found myself flying into Phoenix and taking a long look from above, taking in all the squares and parcels that divided up the land, how they seemed superimposed over the city’s underlying base of dried-out, brown desert floor. Pools glittered out from these little parcels, cutting up the ground into mini-oases. Cars zipped through the I-10, the 202 and the 101, buzzing like multicolored insects. It looked like a computer simulation, a megalopolis expansion pack in a game of SimCity. Phoenix’s Sky Harbor is all kitsch to visitors, cowboys and Indians, Lego miners and pick axes, shoot-outs and adventure. It is the consumable west, turquoise jewelry and rattlesnake tails.

At the state level, Representative David Schweikert once called climate change “folklore.” Representatives Paul Gosar and Andy Biggs expressed similar doubt, unconvinced by the data. Tea Party politics under the Obama administration produced SB1507, a state bill preventing Arizona governments from abiding to the non-binding United Nations Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. Fears of globalism, one-world governments, and restrictions on the libertarian ethic are common tropes in Arizona politics. Phoenix would not be what it is today without a total veneration of property rights (but only the rights of the advantaged).

City planners are still in the midst of these conflicts, trying to determine how high-carbon lifestyles correspond to heat and drought, migration and militarization. Planners in training like myself are continually tracing causalities, rendering the world as a series of cryptic logic models on a chalkboard somewhere. We exhaust ourselves in parsing the future as it relates to the present, the past as it relates to the sprawling forms unfolding and refolding again and again in front of us. The Valley of the Sun sounds less like a metropolitan area of 4.7 million people, and more like the site of an ancient fable, a moral testing ground for a formless American dream.

I picture my own home alongside homes throughout the city, the promises of the newly constructed, the anxieties of the longstanding. This March, I got a text message from my father. “My last day here is August 17; it’s okay.” I found out from my mother that the company he had moved to Idaho for is relocating to Taiwan. My dad will turn 63 this year, just shy of retirement age. He’s disappointed. But he’ll come back to Chandler, Arizona to that corner house. My parents will contain themselves in a shelter of shaded verandas and green parks, away from the hazards and worries of other neighborhoods. My father will remain embedded there, along with my mother, watching movies in the breeze of circulated air. They will see the flowers dry up in the summer heat and be glad for the structure that sustains them.