When my father died, I didn’t cry, no one in my family did, not even my mother who had been with him 56 years. My father was a man who never met his own expectations for himself. No one chased the American dream harder than he did. He put in his hours, was a successful salesman and manager of car and recreational vehicle dealerships.

But those jobs weren’t enough for a man who imagined himself in a Rolex watch and a condo in Florida with a sailboat and the resources to retire early enough to enjoy it all. He was a gambler and he thought he needed just one big win for that to be possible. A boy from Centralia, Illinois, he had too many obstacles to overcome—bad teeth, bad manners, bad habits, a bad temper and nothing left behind from his father.

Nobody in the family had any desire for his things, all the stuff he had collected over the years that sat in the basement covered in a thick coating of dust: a collection of ceramic, wood, and stone elephants, a stamp collection, baseball cards, golf clubs, empty liquor bottles made in the shape of race cars, 20 different winter vests—he never wore a winter jacket.

But what I did take I shoved into my top drawer upon my return home: His death certificate, some worthless jewelry—a gold ND (Notre Dame) necklace, a gold ring with an oblong jade inlay, a slim Bulova watch—a tarnished copper cup with the image of a spy in a trench coat embossed on the outer surface, and his wallet that he had given me before an ambulance took him to hospice.

When I returned home after the funeral, and without looking, I put it all under my unpaired socks, my 2018 tax returns, and a receipt for expensive diamond earrings I bought myself that I didn’t want my wife to see.

When I open that drawer every morning, I look for two matching socks, not remnants of my history, his things being covered up by piles of paper containing my mom’s supplemental insurance plan, prescription coverage paperwork, and power of attorney forms so my older brother and I can act on her behalf as her decline from Alzheimer’s progresses. Why have I chosen my top drawer for these things? We have a small library room, file cabinets, but for some reason I need to be in proximity to my grief, history, and shame.

Are we waiting for what will be rightfully ours or are we looking for some way to escape what we never asked for?It’s his birthday. He would have been 79 today and I don’t feel anything. I open the sock drawer. What’s wrong with me? Am I so disconnected from myself that I eventually won’t be able to feel the love I have for my wife, my brothers, my dogs, my friends? I pull out the mug and jewelry first, inspect them briefly and throw the jewelry into the mug. Then I dig for the wallet wondering why I didn’t open it immediately after his death. Maybe I had just assumed it was stuffed with credit cards with unpaid balances—debt, the only thing my father left behind.

He left nothing for my sick mom’s care and my brothers and I knew there was no retirement windfall in store for us. Rather in the months after his death my older brother and I received regular phone calls trying to recoup thousands of dollars in unpaid charges for cash advances to gamble with, for another pair of shoes, or another Coach purse for my mom, a ruse to convince her he didn’t spend all the money on himself. Twenty-three Coach purses by the time he died.

What gets passed down from parent to child? Are we waiting for what will be rightfully ours or are we looking for some way to escape what we never asked for? When I open the wallet, the small square picture at the right corner of his driver’s license startles me. We are face to face for the first time since his death. The credit cards are weathered, the numbers fading, and white cracks have formed around the edges: two American Express cards, one green, one gold, a MasterCard, a bank debit card, a Visa, and a Macy’s card. I actually think to myself, “not as bad as I thought.”

Though it immediately conjures images of my mom on the phone with a debt collector when I was three, five, nine, twelve, fifteen, twenty. Over the years, phone technology changed dramatically. When I was young, my mom pulled a long coiled cord across the kitchen to the desk where she kept the bills, pleading and crying with bill collectors and collection agencies for more time. The coiled cord became a thing of the past but the calls never did.

I pull apart the wallet and stuck to its inner leather wall is a dollar. One, one dollar bill, ninety-nine cents short of a cliché. “He died without a penny to his name.” I have emotions now, a sadness lodged in my throat—I miss him for the first time. I don’t know what I miss. Maybe I miss the familiarity of all the lies he told—that he had stopped gambling 12 years ago, that the mortgage was almost paid off, that he paid for my brothers and me to go to college—a lifetime of lies we were all complicit in as we nodded our heads and said in unison, “That’s great, dad.”

These lies created a bond between my brothers, mother, and me. Something we could laugh about because what else could we do? Even he would get in on the fun, knowing my mom and I saw him pull a pack of Salem’s out from a planter on the front porch after he declared he hadn’t had a cigarette in over a week. We laughed until our stomachs hurt.

As I put the wallet back into the drawer, I leave the dollar bill inside, look at the photo on his driver’s license one more time, and wonder what I will leave behind.

__________________________________

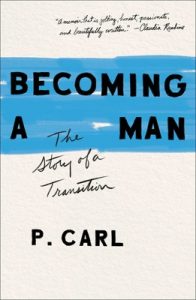

P. Carl’s memoir Becoming a Man is out now from Simon & Schuster.