Feature image, Old Town Before the Battle.

A gash on his left cheek. A hole through the right side of her face, lacerations on her neck, blood soaked into her undershirt and uniform. Bloody pockmarks on his forehead. Six wounds on her neck. A gash on her belly, a circle of rose-colored blood on her white t-shirt. A slash of blood on the left side of his abdomen and a matching wound on the right, his arms at his sides, his uniform otherwise intact. A head wound, out of which blood must have poured, his ear now covered with it, his neck, too, and the collar of his shirt. An injury on her arm, blood dripping past her elbow, her hands crossed on her knees, her body posed on a stool, her face turned to the camera.

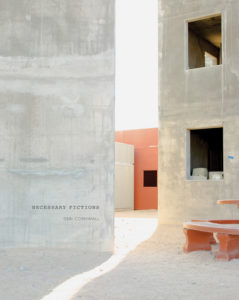

For Necessary Fictions, Debi Cornwall visited mock-village landscapes in the fictional country of “Atropia,” where costumed Afghan and Iraqi civilians, many who fled war, recreate war to help train members of the US military. Real US soldiers—many of them members of the Army National Guard—are dressed by Hollywood makeup artists in “moulage” (fake wounds) for immersive, realistic, pre-deployment training scenarios. Cornwall took pictures of the soldier-actors. She invited them to pose in front of a backdrop in her mobile portrait studio, with their fake injuries and dressed in military uniforms—imagined images of possible real future violence. They sat for a photograph, and then they headed into the field to create war.

“Staff Sgt Jeremy E” from Debi Cornwall: Necessary Fictions. Published by Radius Books, Santa Fe, 2020. Photograph copyright © Debi Cornwall.

“Staff Sgt Jeremy E” from Debi Cornwall: Necessary Fictions. Published by Radius Books, Santa Fe, 2020. Photograph copyright © Debi Cornwall.

All photographs, Ulrich Baer writes in Spectral Evidence, especially photographs of violence, “signal that we have arrived after the picture has been taken, and thus too late.” For critics, like me, who wrestle with whether or not it is ethical to view photographs of people in pain, the viewers’ too-late-ness is part of the equation. If the violence has already happened, if the person is already dead, why should we look? What can be done? But Cornwall’s images offer another alternative: the violence is imagined; the violence can still be stopped.

Those of us who haven’t been to war have to imagine what a wounded soldier looks like because we usually don’t see such images in the media. Photographs of dead or injured service members are hidden, censored, blocked from view. But not all images of the dead are concealed. There are some dead and wounded bodies we’re allowed to see in the media—the bodies of non-Americans injured or killed in warzones in other countries, the bodies of non-Americans injured or killed by natural disasters in other countries, and the bodies of Black and Brown Americans killed by the police. In this context, what do images of imagined violence do? How do Cornwall’s images shape—or misshape—our response to images of actual violence? How do her photographs affect our thinking about war and what it is we ask soldiers to do and to risk when we send them to the battlefield? What are we pretending if we look at them? What are we pretending if we don’t?

“SPC Micahel A” from Debi Cornwall: Necessary Fictions.

“SPC Micahel A” from Debi Cornwall: Necessary Fictions.

I am as interested in the images of violence we don’t see as I am in the images we do see, because hiding some dead bodies affects how other dead bodies are viewed. Especially when the hidden bodies are most often White and the viewed bodies are most often bodies of color. Which victims of violence are offered the privilege of privacy? And when is privacy not a privilege but a form of suppression? Who gets to decide whose dead bodies are seen and whose are hidden? What criteria should we use to make that decision? If the public were granted permission to view all injured bodies—regardless of age or nation, regardless of race or cause of death—might a more equitable sharing of images yield more ethical viewing? And might more ethical viewing yield less violence and more repair?

What do images of imagined violence do? How do Debi Cornwall’s images shape—or misshape—our response to images of actual violence?Photographs of injured or killed soldiers are not the media’s only missing images of violence. We also don’t see images of students killed by guns at school. Students at Columbine High School—who had not yet been born when the shooting there took place in 1999—have started a campaign they hope will help stop gun violence. #MyLastShot asks students across the country to place a sticker on a personal item (cell phone, drivers license, school ID) indicating that, should they be shot to death, they want the image of their dead body to be made public. In the event that I die from gun violence, please publicize the photo of my death, the stickers say.

At the heart of #MyLastShot—and at the heart of the work of most photojournalists and of the work of most of us who study violent images and their effects—is a belief that images can make a difference. On the #MyLastShot website’s homepage is this message in big white letters: Your Final Photo Can Save Lives.

The hope here is that seeing graphic images of gun violence—what a bullet does to a skull, to skin, to heart, to bone—will activate the public and our government to pass gun control legislation. But I don’t think we are yet the viewers the students wish we were. It’s possible photographs of students killed by guns might teach viewers to turn overwhelming emotional responses to images of violence into concrete political action on behalf of the injured bodies we see. But if looking at images of American students killed by guns in school might effect change, why hasn’t looking at other images of other bodies killed by guns, whether in Ferguson or Raqqa, had that effect already?

We already see plenty of photographs of gun violence in the media. The body of Michael Brown, a victim of police violence, a victim of gun violence, was on the front page of the New York Times—his body in the middle of the street, where he laid uncovered for hours, his mother learning her son had been killed when someone showed her an image of his body on a cellphone. It is possible to watch a video of the Fort Worth police officer, Aaron Dean, shoot and kill Atatiana Jefferson through her bedroom window. When Black men and women are shot by the police, their images are everywhere, on the front pages of newspapers, in social media feeds, on websites, offered to American viewers to consume freely and without consequence or accountability.

It is no small thing that three key images on the #MyLastShot website are people of color: David Jackson’s famous photograph of Emmett Till; a photograph of the dead body of three-year-old Syrian refugee Alan Kurdi; and the photograph of Kim Phuc, often referred to as the “napalm girl,” running down a Vietnam road. These student activists use images of Black and Brown bodies to tell their own story, to make their own argument, because, for the most part, we don’t see images of White dead. Viewing photographs of students killed by gun violence in American schools might trouble this racist pattern. Or it might confirm it.

Both cameras and guns shoot, but #MyLastShot adds a third kind of shot to the equation. This is the shot in phrases like Give it your best shot or Shoot for the stars or Call the shots or Big shot. There is agency here—and a kind of threat. Today’s students know that the gun lobby is stronger than the student lobby, better funded, better armed. I read #MyLastShot as a way to claim some sliver of power. Students might not have control over what happens to their bodies when they’re at school, but this campaign gives them control over what happens to future images of their bodies—bodies our government has failed to protect. If you don’t do better, the campaign threatens, you’ll have to see us dead.

Students might not have control over what happens to their bodies when they’re at school, but #MyLastShot campaign gives them control over what happens to future images of their bodies.And a similar threat is operating in Cornwall’s images of service members preparing for the theater of war. When we look at her images—the soldier with the wounded cheek, the soldier with the wounded abdomen—we are looking at what might happen to these bodies when we send them to fight. Are these antiwar images? Might seeing what happens to a body on the battlefield stop people in power from ordering that body to the battlefield? Can seeing an image of possible future violence help stop that violence?

“SPC Francesca C” from Debi Cornwall: Necessary Fictions.

“SPC Francesca C” from Debi Cornwall: Necessary Fictions.

The #IfTheyGunnedMeDown campaign also depends on the idea of future violence to stop violence. After the murder of Michael Brown in 2014, the hashtag #IfTheyGunnedMeDown dominated Twitter, used more than 100,000 times in 24 hours. When the media showed a photograph of Brown on a front porch flashing a sign with his hand rather than a photograph of him in his cap and gown, Twitter users posted dueling images of themselves, side by side, and asked which image the media would circulate should they be killed by the police. Would the media choose the photograph of a man holding his baby or the picture of him with friends at a party? The picture of a woman in her military uniform or the picture of her holding a bottle of vodka? The picture of a man on a couch wearing a gold chain or the picture of him in fatigues reading a book to children in a classroom? These bodies are vulnerable to police violence, the image campaign reminded viewers. How will you see us? Will you protect us?

Cornwall’s images capture vulnerability, too, and part of that vulnerability is shared (all our bodies are soft, permeable, threatened by any sharp thing), and part of that vulnerability is not shared (not all of us will be sent to warzones; not all of us live in warzones). Vulnerable comes from the Latin vulnerabilis meaning “wounding,” from the Latin vulnerare meaning “to wound, hurt, injure, maim,” and from the Latin vulnus meaning “wound.” Vulnerable originally meant both “capable of being physically wounded” and “having the power to wound,” though that second meaning is now obsolete. But both definitions capture what it means to be human: we are vulnerable both to experiencing violence and to committing it.

Vulnerable was one of the words the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tried to ban in 2017. Their list of banned words also included diversity, fetus, transgender, entitlement, science-based and evidence-based, among others. Though vulnerable didn’t receive as much attention as some of the other censored words, it was, for me, perhaps the most frightening prohibition. Recognition of our shared vulnerability is at the heart of every movement for civil rights and peace. Effective social justice work makes vulnerability visible: images of protestors doused with fire hoses and attacked by dogs; photographs of casualties of war, of coffins, of disaster victims; #metoo stories shared by survivors of assault. Denying our shared vulnerability in the face of violence, disease, war, famine, sexism, racism, and environmental crisis can only result in a denial of our shared responsibility to one another and to the planet we call home. To turn away from vulnerability—to fear our precariousness, to deny it—often results in violent attempts to make oneself invulnerable, to neutralize threats, to dominate, to go to war. Though vulnerability is unevenly distributed, though it is inflected by racism and sexism and classism and geography, vulnerability—especially when we remember it once meant both to wound and to be wounded—is a human condition. Admitting our precariousness, naming it, embracing it, can help us better tend the earth and one another.

At the end of “Looking at Images,” Susan Sontag describes Jeff Wall’s staged photograph Dead Troops Talk (a vision after an ambush of a Red Army Patrol, near Moqor, Afghanistan, winter 1986). Wall constructed the Cibachrome transparency—seven-and-a-half feet high, more than thirteen feet wide, mounted on a light box—in his studio. He’d never been to Afghanistan. He read about the conflict, then created this imagined scene: thirteen Russian soldiers in bulky winter uniforms and high boots, “a pocked, blood-splashed pit” and “the litter of war: shell casings, crumpled metal, a boot that holds the lower part of a leg.” Afghans in white strip the dead of their weapons. With wounded stomachs, missing legs, and heads partially blown off—the dead soldiers talk with one another.

Many of the wounded look right at us, their wounds gaping, their faces dusted by explosions. They ask something of us. But what do they want?“One could fantasize that the soldiers might turn to talk to us,” Sontag writes. “But no, no one is looking out of the picture at the viewer. These dead are supremely uninterested in the living.”

And why should they be interested in us? Sontag asks. We don’t get it—and by “we” she means everyone who has never been in war. “We can’t imagine how dreadful, how terrifying war is—and how normal it becomes. Can’t understand.”

But in Cornwall’s Necessary Fictions the moulaged soldiers are supremely interested in the living. Many of the wounded look right at us, their wounds gaping, their faces dusted by explosions. They ask something of us. But what do they want?

What does it mean to look at these imagined images? Does it mean to imagine you have those wounds yourself? Or to imagine that you caused them? Or that you know how to repair them? Or does looking ask for something else entirely?

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes contrasts a photograph’s studium (its general interest) with its punctum—which he defines as “lightning-like,” as “this wound, this prick, this mark made by a pointed instrument,” a “sting, speck, cut, little hole.” The punctum is both what wounds, pricks, and bruises the viewer, and the wound, prick, bruise itself. According to Barthes, the photographer does not purposefully include the punctum in a photograph, nor does the viewer seek out the punctum, rather it comes to (or better, at) the viewer. The punctum, Barthes writes, “rises from the scene, shoots out like an arrow, and pierces me.” Barthes emphasizes the accidental nature of the punctum to highlight the “outside” status he reserves for it—outside culture, language, and code. The punctum must remain unnameable. If he can name it, it cannot wound him. He writes, “What I can name cannot really prick me. The incapacity to name is a good symptom of disturbance.”

Will we choose to be accountable for these future-wounded bodies? Will we let these photographs save their lives?For Judith Butler, being disturbed by that which “comes to me from elsewhere, unbidden, unexpected, unplanned,” is a sign that we are being addressed by an other in a way we cannot avoid. “[I]t tends to ruin my plans,” she writes in Precarious Life, “and if my plans are ruined, that may well be the sign that something is morally binding upon me.”

Cornwall’s photographs wound and disturb and disorient, and they are morally binding. Will we choose to be accountable for these future-wounded bodies? Will we let these photographs save their lives?

__________________________________

From “This Picture Might Save Your Life” by Sarah Sentilles from Debi Cornwall: Necessary Fictions. Published by Radius Books, Santa Fe, 2020. Text copyright © Sarah Sentilles.