What Does It Mean for an AI to Write a Novel?

This Week on the So Many Damn Books Podcast

Eugene Lim stops by the Damn Library to discuss his novel Search History, which sends the conversation careening from AI to authenticity to writing theatrically to songwriting to rainy day ideas, and that spiral leads (as it often does) to discussing César Aira and his work, particularly Conversations. Listen up!

What’d you buy?

Drew: Brian Evenson x 4! The Open Curtain // Last Days // Father of Lies // A Collapse of Horses

Christopher: Camera Man by Dana Stevens

Eugene: O.B.B. by Paolo Javier

Recommendations:

Drew: If A Leaf Falls press // the live-action Cowboy Bebop

Christopher: Christmas: A Biography by Judith Flanders

Eugene: Telephone by Percival Everett

*

From the episode:

Christopher: I was questioning whether or not a novel is your preferred term for what this is or would you have rather come up with your own in Search History—people sometimes change their colon designation, their subtitle. So I was I was curious if that’s fitting for you, if you feel like, “yes, I’ve written a novel—it’s it’s a novel that sits on the same shelf as all other novels.”

Eugene: Yeah, well, I think if you write things that are in the category of experimental fiction, you’re often neither fish nor fowl. Most cases I like it being called a novel because then people can understand what it is or people can put it in the general ballpark. I ran a small press called Eclipse’s Press, and we haven’t for a long time because I haven’t gotten around yet, but we have submissions in the past. And one thing I would say is that we like novels that are weird but don’t necessarily look so better than those that novels that look weird, but actually quite normal.

It’s kind of nice to have like there are things that are very transgressive or formerly they look like they’re unfamiliar or they’re de familiarizing. But when you get to them, a lot of the things are maybe more familiar and maybe more—hackney is a little too strong—but maybe it’s it’s less vibrantly out there than you would have expected. So I like the ones and I like people who actually come at you normally-looking and then you’d talk to him for a while or you read a book for a while and you’re like “oh, this is actually quite strange and quite it’s take me someplace where I wasn’t expecting.” I really like that.

Drew: Speaker 3: It feels right for this book too. I think about a moment in Dear Cyborgs that I has endeared me to you forever. And it’s like they’re talking about, I forget exactly what they’re talking about—they’re like trudging through the snow on the way to a super villain’s lair and just that sort of like very absurd comic book, huge thin, and that moment for me sticks because it is that it’s like, “Oh, OK, it’s a novel.” And then I’m like, “this is not like any novel I have ever read.”

And there’s a sort of ongoing underlying thing in Search History, and as we talk about novels that present themselves more or less normally at first and then sort of get weird versus the novel that’s weird up front—I feel like right now all of the attempts at AI writing are pretty weird up front. But there is this, I don’t know if you both feel this fear, this worry, this question of like, will AI ever be able to write a novel? And that’s a huge thing in this book. And I guess the question is, do you? Do you worry about that, do you think that AI will ever be able to not only pull off like traditional literary fiction, but sort of this more tactile thing that we’re talking about?

Eugene: It’s a question that I’m not, even though the book worries about it, I think what the book is actually worrying about is this inflation-confusion that seems to be right upon us, that is hard for us to even comprehend where the machine and the human are becoming confused and conflated. So the epigraph of the book is friendly with saying “the book is the closest thing to a human being,” and I think we understand how that’s true. you hold a book, you love a book, a writer will say, “I put all of myself on that in that book.” A reader will say, “I hold the writer in my hands,” so you can see how somehow a book spiritually embodies a human being.

These latest AI that are working on this natural language processing stuff, they are being fed the internet, they’re being fed all of our speech and the future ones will be probably fed this conversation. I heard as AI scientists joke like this will be will be fed into this machine in the future. If that’s the case, you put those two thoughts together, a book is the closest thing to a human being, these machines have eaten all of our speech—at some point the which is which is containing more of our humanity? There is a little bit of that as a possibility. I don’t know if this particular structure will be able to do it, but I think that’s an that’s an interesting question: what will that machine, who has all of our thoughts in it, when they spit something out, woll it spit something that will be very human or will be will be moving or and where we would get this energy that is moving us?

So I think that’s an interesting question. I think it’s not that far in the future in some ways, whether we read a book in our lifetimes that we, that a computer writes, and we go and it’s great book. I don’t know if that’s true. But I think that but that whatever is happening with AI’s development right now is i going to have a huge impact on—is having and will have a huge impact. And it’s just like the internet had a huge impact on us. So I think it’s ongoing and revolutionary and also insidious, and we’re inside of it, so it’s hard to see it.

So Many Damn Books

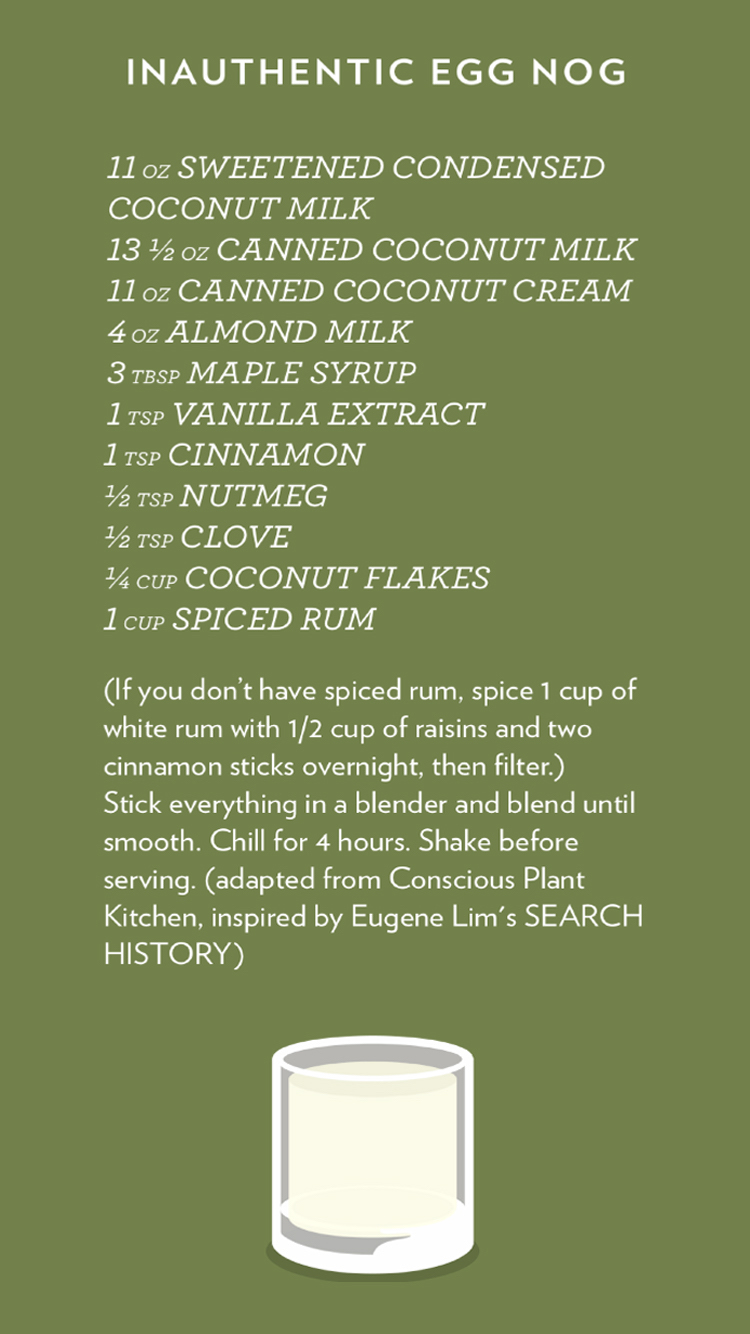

A blessing, a curse, a podcast. est. 2014. Christopher (@cdhermelin) invites folks to the Damn Library to talk about reading, literature, publishing, and trying to make it through their never-dwindling stack of things to read. All with a themed drink in hand. Recorded at the Damn Library in Brooklyn, NY.