What Does it Look Like to Decenter Whiteness in Fiction?

Kasim Ali on Writing for One’s Characters

Decenter whiteness in your writing.

I’m not sure when I first came across this phrase, this rallying cry for non-white writers the world over. Often, this phrase, thrown onto Twitter, comes with no tangible instructions on how to do exactly that.

Read more books by non-white people, the cry sometimes carries on. Decolonize your bookcase!

I started actively seeking out books by non-white people when I reached university, suddenly confronted with the fact that my entire English degree was filled with white writers. I, blustering with youth, confronted my lecturers about it, asking why we weren’t reading books by non-white authors. They told me there were books by non-white authors, on the American module. The books they pointed to were about slavery.

So I rebelled, filled my own personal reading with as many non-white authors I could find.

In stark contrast to my early adulthood, my childhood was filled with white writers: I adored the works of Lemony Snicket, R.L. Stine, Christopher Paolini. It never occurred to me, as a child, to think that these books weren’t reflecting myself back to me.

In my everyday life, though, I never went a single day in my childhood without seeing my face reflected back to me, from my family, my friends, my school teachers, the people who worked in the shops around me. I grew up in Alum Rock, Birmingham. A few miles east of the city centre, Alum Rock was, and still is, populated by majority South Asian Muslims, specifically Pakistani. White people were the ones who stood out. As the years have passed, other kinds of people have moved in: Somali Muslims, Romanian and Polish families, even the odd white family. But the majority remains the same.

I was the boy who grew up in a house of mirrors, my own face reflected back to me wherever I turned.

Consider, too, that I was raised in a household that watched Pakistani dramas and Bollywood films galore. That we listened to Pakistani and Indian music. There was no conversation about whether the books I was reading reflected me because they didn’t need to. Every other aspect of my life did.

Until I reached university, where I was the only non-white person on my entire degree. Faced with a sea of white faces, I felt something crawl under my skin and stay there for three years.

Over that time, I’d find myself faced with a white guy who told me I was stupid for following a religion that wanted the destruction of our modern world; with a white girl who called me Aladdin the entire time she knew me; with a white lecturer who, when I randomly selected Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses for a presentation, told me I could pick again.

It’s no surprise that my writing changed significantly during university. I’d written stories in my childhood that seemed to exist in a nothing-world, no mention of anyone’s race or skin color or religion. Characters just were. But now I found myself writing specifically about people like me.

I spent three years being taught there was no space for me in this world. But I knew there was. I spent the next four years writing book after book. Muslims in space! South Asians in fantasy! Pakistani boys falling in love!

Faced with a sea of white faces, I felt something crawl under my skin and stay there for three years.

I read voraciously: Zadie Smith, Mohsin Hamid, Salman Rushdie, Kazuo Ishiguro, Elif Shafak. I sought out the stories that my lecturers told me weren’t suitable for their modules, and I learnt more from them than I did in my three years studying dead white men.

I learnt how to be from those books, how to live in myself.

*

The idea for Good Intentions came from three moments in my life.

The first: I was good friends with a Black girl at school, a Somali Muslim whom I adored. One day, I walked her to her bus stop and my mother saw us, her car driving past. Later, she asked me who that was. “A friend,” I said. After a moment, she said, “You shouldn’t hang around girls like that.” It would take me years before I understood that she meant Black girls.

The second: I was getting tired of watching Muslim narratives, like Master of None and Hala, which showed Muslims finding their freedom in throwing away their religion. If there was space for those narratives, there was space for narratives like my own, Muslims who didn’t just abandon their religion but forged their own place in it.

The third: Interracial romances irritated me because of how often they were white + non-white. My world was filled with couples who were quite often non-white + non-white. After I watched The Big Sick, yet another story about a non-white man falling in love with a white woman, I decided I was going to write my own.

I decided there wouldn’t be a single white person in the book.

When writing it, I decided there wouldn’t be a single white person in the book. Not a friend, not an ally, not a well-intended teacher. Not a villain, not a racist, not a throwaway moment that allows my characters to grow in learning from it.

They just simply wouldn’t be in my story.

They had their own.

This space was not for them.

*

In thinking about Good Intentions over the past two years, as it has been edited and read by sensitivity readers and by normal readers, as it has been reviewed, I have thought about its relationship to whiteness.

There are no white characters in Good Intentions, so on a very shallow level, whiteness has been removed from the narrative.

But it goes beyond just that.

What I now understand about my writing is that I did not write for a white audience. There are no moments of explanation in this book, about what a topi is or what prayer is being read or what certain food is. I did not write for the white critic, who might wonder why I’m not including conversations about terrorism or what impact an Islamophobic government might have on these characters.

Because the people I’m writing for already know about those things. I don’t have to explain a single thing to the South Asian boy who reads this book, because he gets it. So does the Muslim girl.

Because I was the boy who grew up in a house of mirrors, my own face reflected back to me wherever I turned.

I didn’t just choose to write about these characters; I chose to write for these characters.

And that, for me, is how I decenter whiteness in my writing.

By never considering it in the first place.

_______________________________

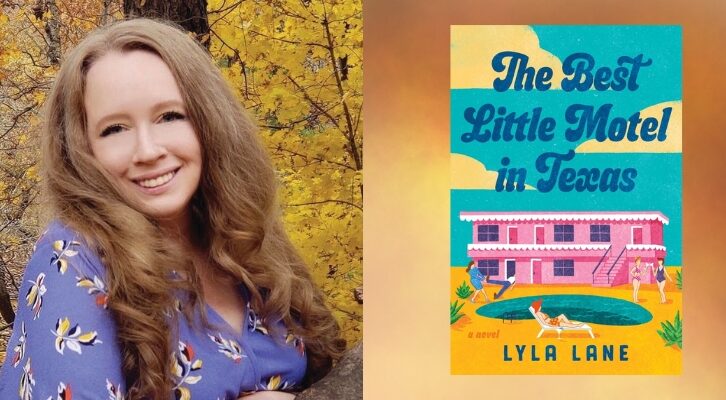

Kasim Ali’s Good Intentions is available everywhere that sells books.

Kasim Ali

Kasim Ali works at Penguin Random House, and has previously been shortlisted for Hachette’s Mo Siewcherran Prize and longlisted for the 4th Estate BAME Short Story Prize, and has contributed to The Good Journal. Good Intentions is his debut novel. He comes from Birmingham and lives in London.