What Does Anger Mean For the Immigrant?

On Coming to America and Taking Off the "Mask That Grins"

When I was in graduate school at Yale University over 20 years ago, I once asked a friend of mine why everyone always gravitated toward us two at student parties. My friend was one of the few black doctoral candidates in the university at the time. Finding ourselves to be the only minority students in a great many of the seminars we attended, we often joked with each other privately about race and identity as a way of blowing off some steam. I recollect that particular conversation—words whispered over plastic cups in a crowded room—well. With each passing year, our playful exchange has taken on Technicolor oracular tones in my mind:

I hear my friend say: “Sharmila, do I really have to explain why everyone comes and hangs out with us at parties? Because we are fun. Because we smile and laugh so much.”

“Why do we smile so much?” I ask him. “My cheeks hurt from smiling so much and I cannot keep it up.”

“We smile,” he tells me, “because it is the only face we can show. If we stop smiling, they will see how angry we are. And no one likes an angry black man.” Or an angry brown woman, I add, silently editing our conversation. “But I think you know this already,” he continues, “and so you smile wide and crack all those jokes.”

At the end of the 19th century, the African American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar wrote,

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes

In the early decades of the 21st century, I know that if I stop grinning, I will frighten others with my anger. Anger is the useless emotion of people with grievances. Civilized people, superior people, capable people manage anger through reason, televised town hall meetings, logic gates, strategic planning, branding exercises, op-eds, and fireside chats with tea and sherry.

In the universities of America today there are angry students who say that when people of paler complexions use pigments to darken their faces and redden their lips for Halloween, when people with blond straight hair wear dark curly wigs in order to dress as a rapper, they are insulting black people. “Don’t curb our freedom and be a killjoy who doesn’t understand that Halloween is about experimentation,” say their opponents. “Children, do you want adults to tell you how to dress? Do you want to whine about microaggressions and institutionalized racism? Remember, out there in the real world, outside college, no one will give you trigger warnings in a boardroom meeting.” Those who think angry students of color are pampered minorities continue, “Institutionalized racism is a figment of your imagination. This is the reign of emancipation. Jim Crow is a chapter in the history books. The empire has folded up its flags and bid farewell to the natives. Stop complaining, pull up your pants, and learn to have a little fun. We cannot go around changing names of buildings just because the name happens to belong to a white man who owned slaves. Think of all the good qualities the slave owner had. Think of all the wondrous things he did for this country.”

“What’s wrong with a little racial ventriloquism? Race is just performance. Race is a metaphor. Race is a biological fiction. Let us perform our identities.” (These are the graduate school educated voices of America.) “What’s wrong with having a little fun?” (These are teenage voices in America.) “Parading in blackface is our cultural heritage. We will fight to protect our heritage.” (That is Dutch people parading as Zwarte Piet, or Black Pete, on Saint Nicholas’s Day.) These voices, I wager, are mostly white.

Why do blackface and brownface bother me? Because I have been wearing whiteface for so long. Because my Halloween never ends. The tricks and the treats are not toilet paper and cheap candy. The truth is that the opposite of blackface is not whiteface. Blackface is jolly, makes fun of others, is entertainment, is a game you get to play when you are already the winner. Whiteface is sad, demeans me, is deadly serious, is a game we play when we know we are on the losing team.

Blackface makes me angry because whiteface is not its opposite. And anger is no longer a heroic emotion. The age of Achilles is over. Gods and heroes no longer rage as the topless towers of Ilium burn. Now anger is a Third World emotion. Anger is a militant black. Anger is a shrill woman. Anger is a jihadi. Because we know this, many of us also hide our anger behind elaborate masks of comedy.

At Yale, I learned that all binaries are false. That race is a biological lie. That the colonizer never fully dominates. That the colonized are never fully subjugated. That there are things called Ambiguity, Ambivalence, Aporia. And those were just the A words. There were also Hybridities, Problematics, and we had to Complicate Things. Outside class, there were people whose cheeks hurt from smiling because they feared the consequences of revealing their anger. Perhaps because we perfected our smiles, students young enough to be my daughters and sons have to be seen raging on YouTube.

“We smile,” he tells me, “because it is the only face we can show. If we stop smiling, they will see how angry we are. And no one likes an angry black man.” Or an angry brown woman, I add.

Almost 20 years after I graduated from Yale with a PhD, in the spring of 2016 I was invited to speak to graduate students at my alma mater. My hosts asked me to speak on racism on campus and the experience of non-white alumni in the workplace. There are many ways of comporting oneself at such an event—in each version I could emerge as the triumphant heroine of my own story. I could speak of hard work and the high road, and end on an upbeat note. I could speak more clinically, do a Produnova vault across critical race theory, and nail my landing with a virtuoso flourish that would demonstrate that there is no such thing as race after all. I could be somber and tragic, listing all the slings and arrows borne patiently since graduation. I could be the comedienne of color who outruns and outguns racism with her swift wit.

We were scheduled to meet on the third floor of Linsly Chittenden Hall on Old Campus, in a classroom where nearly all my graduate seminars used to meet. When I walked into that room, I knew that none of the story lines were right for the occasion. If I could not bring myself to tell the truth in the very room where I was educated, then what was the value of the diploma written in Latin that Yale once gave me? I cannot play the role of the photogenic minority alumna who has managed some small amount of professional success. I cannot be the poster girl for diversity in a glossy magazine targeted at wealthy donors. So, I told them that as a young woman I once sat in that very room and smiled until my cheeks hurt. I confessed that I entertained classmates with elaborate masks of comedy. I said that I wish I had the courage to be as angry as the young people who are protesting institutional racism in campuses all over the country right now.

*

These young people are the Angry Young Men of a new century. In the last century, the Angry Young Men were mostly young white men, working class and middle class. The British playwright John Osborne immortalized the type in his 1956 play Look Back in Anger. There is a famous scene in that play when a young woman named Ali son tells her father that he is hurt because everything has changed, and her husband is hurt because everything is the same. Alison’s father, Colonel Redfern, is a retired British Army officer who’d served in India. Her husband, Jimmy Porter, is a disaffected working class man who spends a great deal of time berating his wife. The play is set in post war London during the twilight years of the British Empire. Colonel Redfern, an upper class military man, is hurt—I would use the word “angry”—because the old days of Britannia’s global power have come to an end in the aftermath of World War II. Jimmy Porter is angry because nothing has changed since the prewar days. The old social hierarchies still hold him down, while dark newcomers appear on the horizon—immigrants from places like Jamaica and Nigeria and Pakistan and India—jostling for jobs alongside native born whites.

I have very little in common with these angry British men—the old one and the young one. I was born in India, the jewel that once sparkled in the British crown. My people are the immigrants who darkened the streets of Jimmy Porter’s postwar Britain, filling its labor vacuum. Yet, Alison’s words have always resonated deeply with me. I have been both Colonel Redfern and Jimmy Porter. I have been angry because everything has changed. I have been angry because nothing has changed.

When the Angry Young Man is white, male, and British, he is a cultural icon, an artistic rendering of midcentury Britain’s social and cultural struggle. When the play was adapted for a film version, Richard Burton played the role of Jimmy Porter. Eventually, the Angry Young Man traveled to other countries. Wherever he went, he was a member of the dominant culture who felt cheated out of his rightful place in society. Can the Angry Young Man be black? Or a woman? Or an immigrant? I think not. There are other words we use for angry blacks, angry women, and angry immigrants. Those creatures are threatening, unnatural, ungrateful, a problem. Because I know this, I have spent many decades carefully arranging my words, my gestures, my clothes, and my surroundings so that I do not appear threatening, unnatural, or ungrateful. I did not want to be the kind of problem who does not receive good grades in school, or glowing letters of recommendation, or college acceptance letters. I did not want to be perceived as the ungrateful immigrant who does not pass her naturalization examination, the unnatural woman who is never promoted at work or paid a salary equal to that of her white male counterparts. I feared being perceived as the threatening creature who might be detained longer by customs and immigration officers, and even worse, whose children might be seen as threats and problems as well. I envy Colonel Redfern and Jimmy Porter—white men can openly rage against everything changing and against nothing changing. I envy them, for their rage is not arrested.

When I arrived in the United States as a young immigrant in 1982, everything changed for me. The Colonel Redfern in me raged against the change, for it made me a minority, marked by race. After I arrived in the United States, I acted as a model new immigrant. I changed my ac cent, my food habits, my dress, and eventually my citizenship. Yet, I fear little has changed. This angers the Jimmy Porter in me. I am angry when a colleague tells me I gained admission into universities only because I am a minority. I am angry when an adviser tells me that I have to learn six languages in order to pass a three language requirement in graduate school. I am angry when a coworker tells me I am an affirmative action hire who does not deserve her position in the office. I am angry when people inevitably assume my white male assistant is my boss. I am angry at myself for feigning ignorance, hiding my accomplishments, softening the sharp edges of my arguments, pretending to lack conviction, throwing the game so I can remain the token minority who brings pleasant diversity to a white workplace. I am angry at myself for hushing my native born son when he complains that a teacher systematically confuses the names of all the brown boys in class. Jimmy Porter went on to become an archetype. Do I dare reclaim his anger?

*

Anger, everyone tells me, is unbecoming. When I was a child in Calcutta, the Bengali society in which I was brought up made it clear that anger was inappropriate in a young woman. English words such as “compromise” and “adjustment” were frequently mentioned—even in Bengali conversations—when talking to a girl whose marriage was to be arranged to a suitable boy. We lived in independent India of the 1970s. Middle class parents in Calcutta sent their girls to convent schools, expecting them to learn mathematics, history, geography, physics, chemistry, biology, and literature in Bengali and English, as well as knitting, needle work, and cooking. As a young girl, I had an ideal vision of myself as an adult: I am wearing a pale pink chiffon sari with a sleeveless, scoop neck blouse. I have stylish platform heels (it was the 1970s after all). My glossy black hair is long enough to reach my waist. My eyebrows are plucked thin. A tasteful string of pearls floats around my neck. My English is fluent and classy. My Bengali is cultured and soft. My penmanship is flawless. My cross stitch embroidery work is spectacular. My hemstitch is invisible. My buttonhole stitch is delicate and uniform. I can cook four kinds of cuisine—Bengali, Mughlai, Chinese, and Continental—without breaking a sweat. My complexion is light and untouched by the sun. This, I imagined, was the ideal woman. No one described her to me. I pieced her together from novels, magazines, films, radio programs, songs, jokes, and the subtle looks of approval and disdain I spied in the eyes of adults.

“Blackface is jolly, makes fun of others, is entertainment, is a game you get to play when you are already the winner. Whiteface is sad, demeans me, is deadly serious, is a game we play when we know we are on the losing team.”

The ideal modern Bengali woman of my vision was never angry. That would be coarse and beneath our station. Anger was associated with the working class, with trade union leaders, with minorities, with the uneducated and the poor, with the weak and the uncivilized. And anger was decidedly unfeminine. If I had read Virginia Woolf at that age, I would have known that my ideal modern Bengali had an older sister in Victorian England. She was called the Angel in the House. When I was a freshman in college, I was assigned to read Virginia Woolf’s sendup of the Angel in a literature class. I recognized her immediately as the woman I once idealized. Woolf said the Angel in the House was “intensely sympathetic,” “immensely charming,” and “utterly unselfish,” and she “sacrificed herself daily.” “If there was chicken, she took the leg; if there was a draught she sat in it.” I read this one line repeatedly because it described with comic precision so many women I knew while I was growing up. I only needed to rearrange Woolf’s English words ever so slightly for them to fit my Bengali universe perfectly. In damp and chilly London, it is a sacrifice to sit in a drafty room. In tropical Calcutta, the Angel sits in the corner where the cool easterly breeze never blows. Since chicken appears less frequently in our rice and fish cuisine, the Bengali Angel takes the cartilaginous tail end of the fish, leaving the delicacy of the fish head or the fleshy fillets for the men. She sits down for her meals after the men have their fill and considers it a badge of honor to eat off her husband’s dirty plate.

I had another secret ambition as a young girl. I wanted to be the prime minister of the nation. I did not see these two dreams—being the chiffon sari wearing, fishtail eating Bengali woman and being the political leader of the nation—as contradictory. Indira Gandhi was the prime minister of India when I was a young girl. Unlike American girls, I did not have to wait until the 21st century for the political glass ceiling to be cracked. If Mrs. Gandhi could run the country in her elegant cotton saris, we young girls could easily see ourselves running for elections, making laws, and giving speeches from Delhi’s Red Fort on Independence Day. As it turned out, I never did grow my hair long or own a pink chiffon sari or run for public office. And fish tails never appealed to me.

During the 1970s, I was surrounded by fierce and powerful women of another variety. The beautiful goddess Durga—with ten arms, four children, three eyes, and one blue husband rides her lion ferociously through my childhood years. She slays demons that no male god can defeat. We await her visit to her earthly home each autumn for five fragrant days when the coral tipped, white sheuli flowers bloom. In Bengali, we call those five sacred days shashthi, shaptami, ashtami, navami, and dashami. After Durga leaves us and returns to the realm of the gods, Kali arrives. The goddess Kali is ever present in Bengali life. She is no simple mother goddess. She is murderous in her rage. Yet, we adore her as our mother and daughter. Kali, for me, is the closest equivalent to the angry god of the Hebrew Bible. She is rather different, of course, from the deity Moses encountered on Mount Sinai. Kali is a dark skinned goddess, naked, usually depicted with a skirt of severed hands, a necklace of skulls, hair flowing in black waves. Her anger is a necessary part of life. Destruction can never be separated from creation and preservation. There is, however, a small catch. Even destruction has to be destroyed. Kali is depicted in Bengal with her red tongue lolling, frozen in the moment when she steps on the prone body of her husband, Shiva. She is the personification of anger arrested.

Goddesses were not the only women allowed a little bit of rage in my adolescent universe. Epic heroines could rage freely as well. Draupadi, the wife of the five Pandava brothers in the Indian epic the Mahabharata, always appealed to me more than the long suffering Sita in the Ramayana. Sita might have walked through fire to appease her husband Ram’s insecurity, but Draupadi speaks up when her husband stupidly loses a game of dice and makes her the property of his cousins. She does not accept her degradation silently. She leaves her hair undone and announces that she will tie it up only after she has washed it in the blood of her tormentor. Draupadi, as every little girl who pays attention to the Mahabharata knows, holds on to a grudge, refuses to take the high road of forgiveness, and exacts her revenge. When the great war is over in the Mahabharata, Draupadi finally gets to wash her hair in her enemy’s blood. She was no Angel in the House.

“The ideal modern Bengali woman of my vision was never angry. That would be coarse and beneath our station.”

Right around the time I started reading the Mahabharata in various Bengali editions prepared for teenagers, I also discovered Louisa May Alcott’s 19th century classic Little Women, written for children of a different country, of a different era. The Mahabharata offered in print a world with which I was already acquainted. When my mother fed me lunch, when my aunt combed the tangles out of my wet hair, when my grandmother rubbed Jabakusum hair oil into my scalp, they told me stories from the Mahabharata to distract, educate, and entertain. If there was a time in my life when I did not know that Bhima defeats Duryodhona or that Karna is Kunti’s first born son, I do not recall that time. American children’s books, in contrast, transported me to an unknown terrain through the printed page. When I read the Indian epics, printed words gave shape to emotions, smells, and sights already familiar. When I read American or British books, the words on the page made the unfamiliar recognizable. As a result, when I immigrated to Jo’s New England later in my life, I saw the landscape, tasted the food, and felt the chill on my skin first through Alcott’s words. As Prospero teaches Caliban to name the sun and the moon in The Tempest, Alcott gave me the first words to name things in my new home. The dove colored book Marmee gave Beth revealed a New England shade that no Pantone color will ever capture.

Jo March’s temper fascinated me. Her mother, Marmee, was no stranger to anger herself. Mr. March and Professor Bhaer trained their wives to control that temper. As much as I loved reading about Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy, and Laurie, I always disliked the pedantic, priggish side of the novel.

When I first read Louisa May Alcott’s stories, I had only the vaguest sense of their context. Unburdened by knowledge of New England, the American Civil War, or 19th century American society, my adolescent imagination relocated the March family to the same magical place outside of time where the Pandavas and the Kauravas, or Ram and Sita, or Ali Baba and Sinbad resided. In India, I had read Little Women as an allegory— much like John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, the book the girls receive as a Christmas gift from their mother at the beginning of the story. When the specific is unknown to us, most of us are tempted to reach for the general. Novels about “foreign lands” are often read as full-blown national allegories by literary critics. The four girls, their parents, their home, their travails were a fuzzy stand-in for all of America.

Once I understood why the Civil War was being fought, I came to see that the March family represented only one part of America—white, northeastern, Anglo Saxon, Protestant. What is more, I started to perceive that the book was written from a very specific perspective as well. These little women no more represented all girls in the United States of that era than the narrator represented all possible narrative voices. The first part of the novel we now call Little Women was published in the United States in 1868, three years after the end of the Civil War, and five years after President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation declared “all persons held as slaves” to be “forever free.” As a young girl living in independent India, I was unaware that the America in which the March sisters lived withheld freedom and full citizenship from so many of its inhabitants because of their race. Today, I try to imagine an all-black-cast production of Little Women. How would a black Jo fare in the United States during the 1860s? Or a Hispanic Jo? Or an Indian Jo? Or a Chinese Jo? How would Jo write her story if she was not white? How would she write her story if she was one of the Hummels, a first generation immigrant?

*

In 1982, a little over half a million legal immigrants entered the United States. The numbers are surely much greater if we include the undocumented in this rough tally. Some stayed and flourished. Some left after a while. Others fared poorly and were disappointed. Many of their descendants are American citizens now. I arrived in the United States during the second week of August in 1982. I was nearly 12 and accompanied by my parents when we landed in Boston’s Logan International Airport. Before arriving in Boston, I had never left Asia, or even traveled beyond the borders of India. That year, the Immigration and Naturalization Service provided us aliens with many forms, a Social Security number, and occasionally a Resident Alien card. I received a bonus gift from the INS that year. I got race.

The uniquely American concept of race that I inherited upon arrival was shaped by two symmetrical genres of early American writing—the captivity narrative and the slave narrative. Both genres racialize religion and religionize race. In the last couple of decades another type of race narrative has appeared on the horizon—the clash of civilizations theory. This theory has made explicit the implicit intertwining of race and religion in the West since the Protestant Reformation. If you listen closely to American race talk today, you will hear the echoes of old slave narratives and captivity narratives; and you will also discern shades of the idea that Islam and Christianity, much like the Rebel Alliance and the Galactic Empire, are locked in perpetual enmity.

The election of the 44th president of the United States led some to declare that race was a place best glimpsed through the rearview mirror. The election of our 45th president cautions us that the postracial world, should we wish to enter it, remains a mirage shimmering on the horizon, redlined and gerrymandered, walled and banned. Even though race is largely understood as a biological fiction by scientists, even though many American writers have questioned the fact of whiteness, racism is as much a social reality for my generation as I suspect it will continue to be for my children’s generation.

I am a Hindu, with no cross or crescent, no church or mosque, no covenant with one true god, no commitment to the doctrine of sola scriptura. There is no exact equivalent for “religion” or “race” in my mother tongue. Multiple languages and writing systems—Bengali, Hindi, English—have formed the ideas, including that of race and religion, that I carry within me. What happens when race is not inherited at birth, but acquired, even chosen, later in life? What happens when you get race after you arrive as an immigrant to the United States? Throughout this book I will use the odd formulation of getting race because I want to show you how I once perceived race as an alien object, a thing outside myself, a disease. I got race the way people get chicken pox. I also got race as one gets a pair of shoes or a cell phone. It was something new, something to be tried on for size, something to be used to communicate with others. In another register, I finally got race, in the idiomatic American sense of fully comprehending something. You get what I’m saying? Yeah, I get you.

While most native born American authors write about race—angrily, passionately, elegiacally, tersely—as something they did not really choose but had forced upon them since birth, I will write about race as something once alien to my universe and later naturalized. Looking back to 1982, I now realize that race was the immigrant and I was the homeland where it came to rest. Instead of rejecting it as I once did—most of my Indian intellectual friends would consider it a silly American affectation to identify as a “person of color” and prefer instead to think in terms of social class, of majority and minority religions, of imperialists and subalterns—I eventually chose to keep race, despite its unlovely history, its elusive and fictional nature. It is not the accent I carefully picked up from watching television after school, or the way I learned to talk about books at Ivy League universities, or the way I copied the food and drink habits of those around me, or even the way I learned to make the right mistakes in English (because only ESL speakers use perfectly starched and ironed English), but getting race that made me fully American.

In order to tell this story, I must steal some ire from the gods and epic heroes. Let Draupadi hold her grudge as the war of Kurukshetra rages. Let Durga slay the demon Mahishasura this autumn and every autumn to come. Let Kali rage, unchecked by Shiva. In their cozy American parlors, let Marmee and Jo not be hushed by Mr. March and Professor Bhaer. In Bloomsbury, London, let the Angel in the House breathe her last once more. Let Achilles rage outside the walls of Troy so a new story may be plotted.

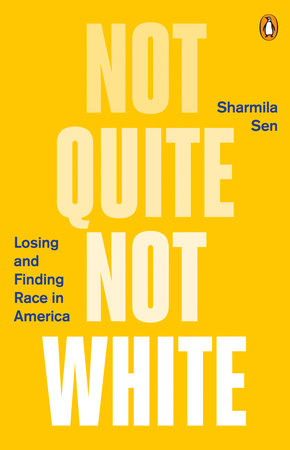

Not Quite Not White immigrant’s pagan confession, an assimilationist’s tongue-in-cheek DIY manual for whiteface performance, and the story of an American’s long journey into the heart of Not Whiteness.

![]()

From Not Quite Not White by Sharmila Sen, courtesy Penguin Books. Copyright 2018 Sharmila Sen.

Sharmila Sen

Sharmila Sen grew up in Calcutta, India, and immigrated to the United States when she was 12. She was educated in the public schools of Cambridge, Mass., received her A.B. from Harvard and her Ph.D. from Yale in English literature. As an assistant professor at Harvard she taught courses on literatures from Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean for seven years. Currently, she is executive editor-at-large at Harvard University Press. Sharmila has lived and worked in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. Sharmila resides in Cambridge, Mass., with her architect husband and their three children. Her memoir Not Quite Not White is out now from Penguin Books.