What Do We Mean When We Say Women’s Fiction?

Liz Kay on Broadening the Scope of Stories By and For Women

The first time someone referred to my novel as Women’s Fiction—the less infantilizing term for chick lit—I died a little inside. But the truth is that most of the books I read are by women. I like reading deeply drawn characters and the machinations of relationships and families. I’m not drawn to crime stories. I’m not drawn to overtly masculine grit. I read dark, complicated literary fiction and I read sharp, funny commercial fiction. Nine times out of ten, these are books written by women.

But there’s something about Women’s Fiction as a category—books that, because of their subject matter usually, are deemed not serious enough to be of interest to men. As readers, we know these books when we see them. We know them by their covers, their jacket descriptions. There’s something about the way these books are marketed that tells us the pages inside are meant to be easily consumed, that they might be smartly written, but the reader herself will not be required to think. There’s something vaguely misogynistic… no, scratch that, there’s something overtly misogynistic about a whole category of books whose central promise is to not shake up the world as the reader already sees it. These are books that are comforting or at least comfortable; they match the stories we’ve always been told about who’s good and who’s bad, about which of us have value.

As women, most of what we’re surrounded by is some form of instruction.

Of the two central characters in my own novel, neither of them is particularly “good.” It is called Monsters: A Love Story after all, which I worried was a little heavy-handed. Am I being didactic? I thought. How naïve I was. Because books for women are supposed to have a thesis. At least on some level there should be some instructive quality—how to be a woman, or how never to be a woman. There’s a lack of moral ambiguity, as if women readers can’t suss out the issues and errors of the characters all on their own.

As women, most of what we’re surrounded by is some form of instruction. There are the glossy magazines that tell us what kind of makeup to buy and exactly how to apply it. There are the celebrity gossip rags for walking us through the intricacies of tearing another woman apart. There is the narrow sliver of women who are held up as beautiful, and then there are the reminders that ultimately what counts is on the inside, though for those of us less genetically blessed it’s especially important that we make sure our insides really sparkle—no being strident or opinionated, no being a dumb blonde who only cares about shoes (PS turn to page 52 for this seasons must-have shoes!).

Even entertainment for women is instructive. We get stories about how to be better mothers, or how to understand our own mothers, or how important the bond between sisters is. We get romantic comedies that remind us that we too can be chosen if we just fix whatever it is that’s broken—our workaholic tendencies? Our distrustful independence? Our slutty ways? Something is broken in us, and if we fix it, we’ll be rewarded with the love that tells us, yes, we have value.

In Women’s Fiction, our protagonists struggle with specifically “feminine” flaws. They can be clumsy, of course, or have a whole host of superficial physical imperfections that make the characters more relatable—an extra few pounds, a poor sense of style. Ideally, these characters should at least imagine themselves to be plain, because is there anything more attractive in a woman than a lack of confidence? They can be high-strung and spend the course of the novel learning to let go. They can be cowed and have to learn to stand up for themselves. They can be damaged, of course, as women so often are, temporarily undone by some sort of trauma.

One of my favorite characters in recent Women’s Fiction, the titular Bernadette of Maria Semple’s Where’d You Go, Bernadette? is one such damaged woman, but there’s a subversiveness to the way Semple explores the trope. The fun of Bernadette is her sheer nastiness at the start. Accused of running over the foot of another woman in the school pick-up line, she says, “I would laugh at the whole thing, but I’m too bored.” The negativity of her character is defined not by pettiness or a vindictive spirit, but by sheer disdain. It’s an aloofness unusual for a female protagonist, but what makes Bernadette really stand out is the nature of her trauma. She’s a victim of a typically “masculine” sort: that of frustrated ambitions. A genius without an outlet, she’s thrown herself into motherhood, but while her relationship with her daughter is lovely, she’s lousy at the rest of it. She neither seeks nor finds fulfillment in home-making. She’s not looking for fulfillment. She’s just in hiding. And this is the brilliance of Semple’s subversion; she doesn’t break the rules of the trope, she just broadens the scope of what’s possible for a female character. Bernadette doesn’t come home to find herself as these characters so often do. What we learn instead is that even at home, Bernadette has been, in many ways, missing.

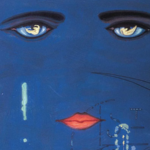

More subversive still is the damaged woman who never overcomes. Naomi Hill of Rebecca Rotert’s Last Night at the Blue Angel is one such character. Telling the story in alternate viewpoints, Rotert follows just enough of the rules of Women’s Fiction to give us the sympathetic Sophia, Naomi’s ten-year-old daughter, who describes herself standing in the wings as her mother takes the stage: “That was me. It was the summer of 1965, and this was the night my mother became famous.” An alcoholic, adoration-hungry narcissist, Naomi spends much of the novel alternately winning and ignoring the affections of her daughter, her various lovers, and her steadfast friends, but it’s only on stage, under the lights, caught in the gaze of a struck audience where it’s ever enough for Naomi. Like Bernadette, she’s driven by ambition, but unlike her, Naomi’s ambition is to finally, finally have enough love. Whether fame ultimately satisfies her remains to be seen, but she sets out to get it, and get it she does. Is there a less deserving character? Probably not. And this is Rotert’s supreme subversion. Naomi may not be traditionally likable, but we can recognize in ourselves glimpses of that kind of wanting.

In Theresa Rebeck’s I’m Glad About You, it’s the world the protagonist Allyson lives in that’s so recognizable—not the glamour of her life as a rising star, but the expectations for women that come with it—beauty, thinness, sexual availability. Unlike the traditionally strong heroine who remains unsullied in the face of a corrupt world, Allyson meets and trades on these expectations to get what she wants, sleeping with a famous director, wearing the dresses he sends her, dresses that make her look both “like a whore and a goddess.” While she takes a stand eventually, her willingness to exploit the hand she’s been dealt forces us as a reader to question how much we’d be willing to compromise. And aren’t these the questions we should be looking to answer? It’s uncomfortable sympathizing with a character for things we don’t necessarily admire, but it’s human in ways that better us. Fiction, all fiction, should challenge and expand our empathies, not simply reinforce the same assumptions, the same rules.

I want a love story where the love isn’t earned and it doesn’t communicate value.

As a reader, I want the stories about mothers and sisters and lovers, but I want the ugly ones too. I want the relationships that never get fixed. I want the people who stay broken and still get picked. I want a love story where the love isn’t earned and it doesn’t communicate value, where it’s just people, human beings having feelings and then trying to figure them out, where love isn’t the prize at the end that you win by being good.

If the protagonist of my novel has a central flaw, it’s that despite being an intellectual woman and a feminist, she’s still struggling with (losing the struggle against) internalized misogyny. She has swallowed most of the messages about how to be a woman in the world—how to be beautiful, how to be thin, how to have value. And here’s a spoiler for you: she never wins. None of us do, and it wouldn’t matter if we did because there’s no way out of being punished for whichever way of being a woman you ultimately choose.

My protagonist is not a heroine who fights the good fight or learns her lesson or overcomes her flaws, nor is she sufficiently punished for the things she does wrong. And there’s no moment in the book where you might be able to pinpoint why she is the way she is. It’s funny, we ask that question about characters a lot. But we ask it differently across the genders—for men, we ask why? what’s his motivation? what’s the thing he really wants? When we ask why about a woman, we mean what’s her excuse? That’s the thing about my protagonist; she’s got no excuse. I’m tired of women always having to have excuses.

In writing my novel, I wasn’t interested in either holding up or critiquing the behavior of one woman—whether she drinks too much, or uses profanity, or is too promiscuous or alternately too cold. She’s too demanding; she doesn’t stand up for herself. She is all of those contradictory things and more, so which do you want to censure her, censure any of us, for? All these instructions, day after day, moment after moment: this is the way to be a woman, no this is, no this. Whatever it is you’re doing, you’re doing it wrong.

I don’t want to talk about how to be a woman in the world. I want to talk about the world we’re being women in. And more and more of the books I’m reading, books by women and books for women, are pushing harder and farther into that ambiguity, letting their female protagonists be humans instead of just role models. And if that’s the direction we’re moving toward in Women’s Fiction, then I’m all in. Because I do write primarily for women, but what I refuse to accept is that with women as readers I need to lower the bar.