What Do We Mean When We Say a Novel is Without Plot?

Rónán Hession on Writing a Reflective, Digressive, and Quiet Novel

Releasing a debut novel means that this is the first time I have had my writing reflected back at me. I feel like a life model in an art class who has sat before readers for hours, after which they turn their easels around to show me what I look like to them. And I, of course, smile and say, “Hmmm.”

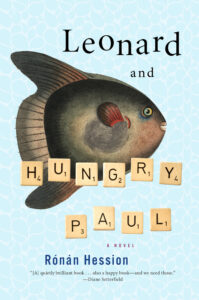

The book, Leonard and Hungry Paul, is about quiet, gentle people who are trying to figure out how to engage with life without becoming overwhelmed by it. Its central subject is human nature; in particular, those aspects that often get overlooked or undervalued in our noisy, competitive world. Perhaps as a result, the book is often described back to me in reviews as plotless, or at least as one where not much happens.

That description is not necessarily intended pejoratively, and I am not especially sensitive about it. It’s simply a signal that the reader has mentally classified the book in the same place as slow Italian movies, ambient electronic music and abstract paintings that don’t really look like anything. The other variant on this comment comes from a creative writing orthodoxy which holds that stories should conform to certain patterns, are arc-shaped and built around things like conflict and resolution, and that real writers kiss and show, but never kiss and tell.

I suppose I could try and make the case that Leonard and Hungry Paul is full of plot; after all, there is a wedding, a competition, crunch conversations, judo. I could argue that each sentence is bursting with plot from the very outset: “Leonard was raised by his mother alone with cheerfully concealed difficulty, his father having died tragically during childbirth.” I mean, come on.

The thing is, this conversation is not really about me or Leonard and Hungry Paul. It’s about how we engage with the core aspects of narrative and the conventions regarding novel writing that have gained currency in the contemporary discourse about the novel as a form. As a writer I have an interest in ensuring that this discourse maintains a wide perimeter fence so that I can gambol about in my imagination without getting electrocuted. But at the same time, I recognize that there are valid points to be made about what constitutes quality writing as an art, and what it is that distinguishes a novel from other written forms.

Releasing a debut novel means that this is the first time I have had my writing reflected back at me.

In my own writing, I am not much interested in plot as a linear unfolding of cause and effect, where things kick off early before working towards some form of resolution, leaving us at a point of closure. If I throw a tennis ball in the air, we have an inciting event; then we have tension while we wait and see how high it goes, followed by the increased tension over whether I’ll catch it. It either lands back in my hand or I drop it, or a stork swoops by and swallows it: something happens that signifies the end of the story.

What interests me, however, is whether the person throwing the ball is changed by the experience; if so, how are they changed? How aware are they of the change and what do they do with that knowledge? In other words, what fascinates me is transition, personal transition to be specific. Why? Because it houses insight. Humans are so adaptable that in the face of change, our tendency is to rationalize, nail down and give expression to our new situation, and in the process, identify with it—it becomes absorbed into our sense of self. There is a brief period where we are between states, and it is in this rich seam where we can learn about ourselves and, through fiction, learn from others.

In Leonard and Hungry Paul we see a cast of characters who have found a way of being in a world, which then becomes disrupted. That disruption does not come from conflict or drama but from self-awareness. It comes from noticing.

In order to capture these transitions, it was necessary for me to slow down both the characters’ lives and the reader’s experience. Insights are unlikely to flower—and that flowering is unlikely to be noticed—amid frenetic activity. By including “rest chapters” in the book and spending time with the characters when they are being unproductive, we pick up the rhythm of their lives and start to synchronize with their thought patterns. We are no longer reading on our own terms, and in that sense, we partake in the transition we are reading about.

One thing that appeals to me about my favorite reflective writers—people like Daša Drndić, Jon Fosse, and Mathias Énard—is the way they embrace chaos. Their writing feels unstructured on the page. It deprives the reader of a familiar sense of perspective. It is digressive. It holds your attention, yet frustrates any idea you might have about reading productively. It is somewhat outside of our perception of time—it is neither fast nor slow, but feels like a deeper version of now. It is radical in rejecting the idea that reading (or writing) is a task that must be performed efficiently.

Humans are so adaptable that in the face of change, our tendency is to rationalize, nail down and give expression to our new situation, and in the process, identify with it—it becomes absorbed into our sense of self.

Of course, this type of writing is not without risks, nor is it a license to writing boring or self-indulgent prose. Stream-of-consciousness is not the same as stream-of-unconsciousness. Unfiltered mental chatter is as dull on the page as it is in real life. It is important for the reader to get a sense of considered thought behind the words; of the writer spending time with the ideas before expressing them.

If I were to start a fight in bar full of writers, I would jump up on the table and yell in a boorish voice that resolution either is or is not important—a statement that is the equivalent of a literary glove slap. In Leonard and Hungry Paul, I was averse to using a load-bearing ending, while also looking to avoid a non-ending that could be considered a cop-out. I didn’t want it to seem unfinished or for the reader to feel cheated. I prefer to think of my books in terms of coherence rather than resolution. I want the story to feel complete rather than just over; I like to leave the reader with the sense that the characters are still out there living their lives.

For all that, questions of plot and structure are not simply technical matters regarding writing technique. I continue to have questions about myself, who I am, my place in the world, and where society is headed. I write reflective books because they are born of my own reflections. There is a place in the world for that and a place in literature for that.

__________________________________

Leonard and Hungry Paul by Rónán Hession is available now via Melville House Publishing.

Rónán Hession

Rónán Hession is an Irish writer, musician, and social worker based in Dublin. As Mumblin’Deaf Ro, he has released three albums of songs, and his most recent album, Dictionary Crimes, was nominated for the Choice Music Prize for album of the year. Leonard and Hungry Paul is his first novel, and was shortlisted for an Irish Book of the Year award.