What Do Americans Really Want to Read? We (Might) Have the Answer

Tom Comitta Explores the Country’s Literary Imagination As Revealed Through Public Opinion Polls and Surveys

The story begins in the 1990s, not long after the fall of the Soviet Union and the emergence of twelve new democracies. In this climate, the Soviet-born, U.S.-based artists Komar and Melamid cooked up a plan to submit art to one of democracy’s most sacred tools: the public opinion poll.

Collaborating with The Nation magazine and a leading polling firm, they surveyed the aesthetic tastes of the United States, posing the question: What does the average person want in a painting? Their poll measured everything from favorite color to painting size to preferences for realism or abstraction. With the data in hand, they created two paintings: one with everything people statistically desired, America’s Most Wanted, and another with everything they did not, America’s Most Unwanted.

The former work is dishwasher-sized and features a blue sky above an autumnal landscape populated by George Washington, school children, and some deer. Composed in the style of Thomas Kinkaid, it is the perfect counterpart to America’s Most Unwanted, a paperback-sized canvas containing thickly painted triangles of beige, yellow, and orange. This “lesser” painting looks like a child’s attempt at a Kandinsky—“my kid could do that” raised to the highest degree.

Three years later, the composer and neuroscientist Dave Soldier conducted a similar experiment with musical taste, measuring what people most like and dislike in music and using the data to compose two songs. “The Most Wanted Music” is a five-minute blend of R&B, rock, and smooth jazz featuring synthesizers, guitar solos, and a climactic key change. “The Most Unwanted Music” clocks in at twenty minutes and features accordions, organs, banjos, bagpipes, an opera singer rapping to cowboy music, children belting Walmart jingles for various holidays, and a long political rant.

What might a poll reveal about contemporary American literary taste and culture? Might it give us more insight into the so-called “American imagination?”

While all four works are rooted in skepticism and humor, they ask serious questions: What is good art and music? Who defines them? Is there something innate in the appeal of a five-minute blend of R&B, rock, and smooth jazz, or were those just the genres playing on the radio at the time of polling? The paintings and songs also poke fun at the tradition of polling—this quixotic attempt to distill the desires of millions into tidy figures. Some sociologists even argue that “public opinion” doesn’t exist, that the majorities we identify in our polling are only real once you measure them and turn them into actionable information.

Thirty years after the first art poll and at a new—and very different—inflection point in the history of democracy, my new book People’s Choice Literature: The Most Wanted and Unwanted Novels asks similar questions. Like Rip Van Winkle waking from his epochal slumber, this book and its survey-driven research on literary taste (published here for the first time) resurface an old method while bringing new techniques and questions to the fore: What might a poll reveal about contemporary American literary taste and culture? Might it give us more insight into the so-called “American imagination?” What might such a poll and its resulting narratives reveal about what people are collectively drawn to or avoidant of, whether they’re conscious of them or not?

While public opinion research has been around for over a hundred years, in the three decades since the first People’s Choice projects, data has transformed from a useful tool for marketers and politicians into one of the most lucrative commodities on the planet. Each day our taste is mined by nearly every website and app we engage with; this data is then processed and spit back out at us in the form of personalized ads, news feeds, suggested videos, and so on. Our data allows these websites and apps to sculpt a bubble of taste for each of us, one that is almost impossible to escape in an online climate designed not to challenge our desires but to hone them even further—to keep us coming back again and again to the things we like, as if we needed further incentive.

In the world of literature, this process is less visible and less frequently discussed. As we learned from studies like Dan Sinykin’s Big Fiction and Mark McGurl’s work on MFA programs and the Amazonification of print culture, literature has had its own honing of taste. In the publishing world, the past century has seen hundreds of small presses, through a long process of buyouts and mergers, fuse together into the five big publishing houses that now dominate 80 percent of all books published in the United States each year. These conglomerates, often called the “Big Five,” seem more concerned with the bottom line than with art or literature. Comp titles—a list of three to five books that agents and authors send to prospective publishers to show how similar books did in the marketplace—rule the day, weeding out anything that varies from what has already proven itself as sellable. Originality and experimentation are obstacles rather than assets and are largely ignored by a publishing industry that, with some exceptions, rushes to the middle over and over again. It’s in this climate that People’s Choice Literature was born, adopting the science of public opinion research to examine what people actually want in their fiction—while exploring alternate routes of readerly desire.

The National Literature Survey

Writing a poll is kind of like writing a sonnet; you follow standards that nearly every pollster employs while adding your own personal twists along the way. In the world of public opinion research, these standards include everything from question types (multiple choice, open answer, ranked voting, etc.) to how one orders these question types (variation is crucial) to the length of the survey (poll fatigue is a real thing). Like a poem, a poll should also anticipate as many readerly perspectives as possible, wording questions so that everyone from avid readers to people who haven’t touched a novel since grade school can understand them.

Katherine Cornwall, a Johns Hopkins-based social scientist and survey design expert, guided me through all of this, helping turn my original poll—a remix of Komar and Melamid’s art and Dave Soldier’s music polls—into one that not only met contemporary survey design standards but sought to cover as many aspects of novels as possible. These questions ranged from reading habits (“How many novels on average would you say you read in a year?”) to writing mechanics (“Which perspective do you prefer when reading a novel? First person? Second Person? Third?”) to character qualities (“What kind of morals do you want a main character to display? Good? Questionable?”) to story types (“Which kind of storytelling technique do you prefer? A sequence of flashbacks? A straightforward story? A stream of consciousness?”). Over the course of two days in December 2021, 1,045 respondents from nearly every corner of the United States worked their way through the seventy-six questions.

After obtaining the data, Katherine tallied the results. Then I parsed them into two lists, or “recipes,” for how to write two very different novels—one containing everything that received the most votes in each question and another with everything that received the fewest or no votes. Below, I’ve reproduced these lists along with the percentages that determined each data point’s wantedness or unwantedness.

The Most Wanted Novel

General

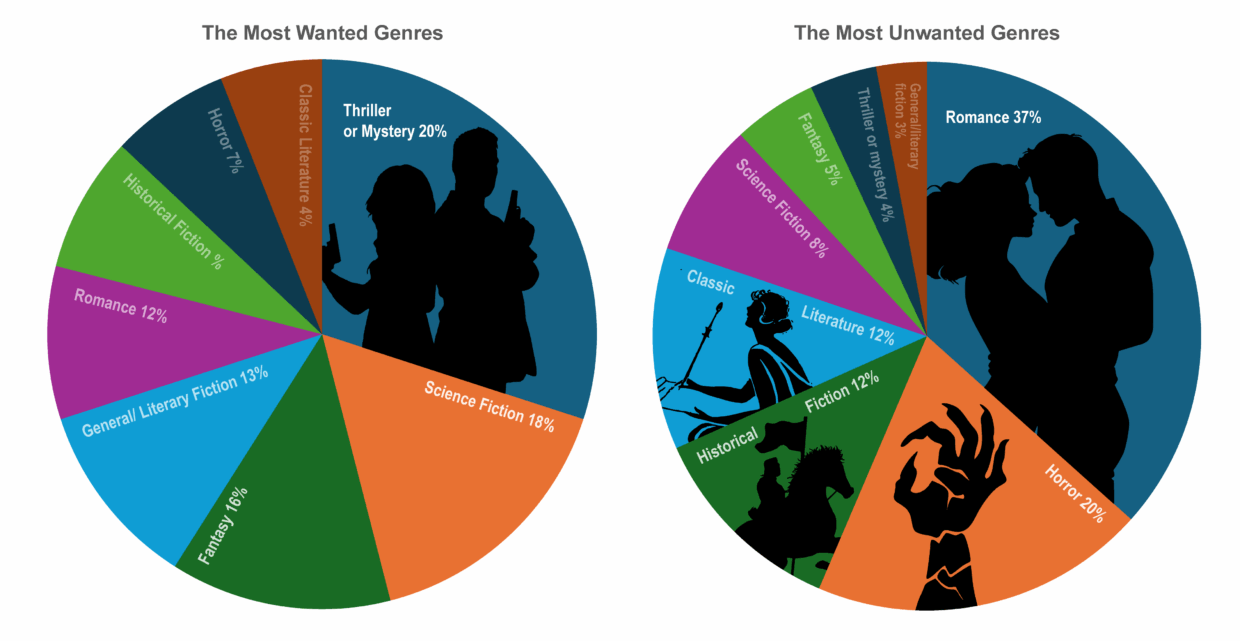

Genre: Thriller or mystery (20%)

Length: 200–300 pages (36%)

Perspective: Third person (56%)

Tense: Past Tense (67%)

Storytelling technique: Straightforward (54%), as opposed to things like stream of consciousness, nested stories, etc.

Style: Realistic (74%)

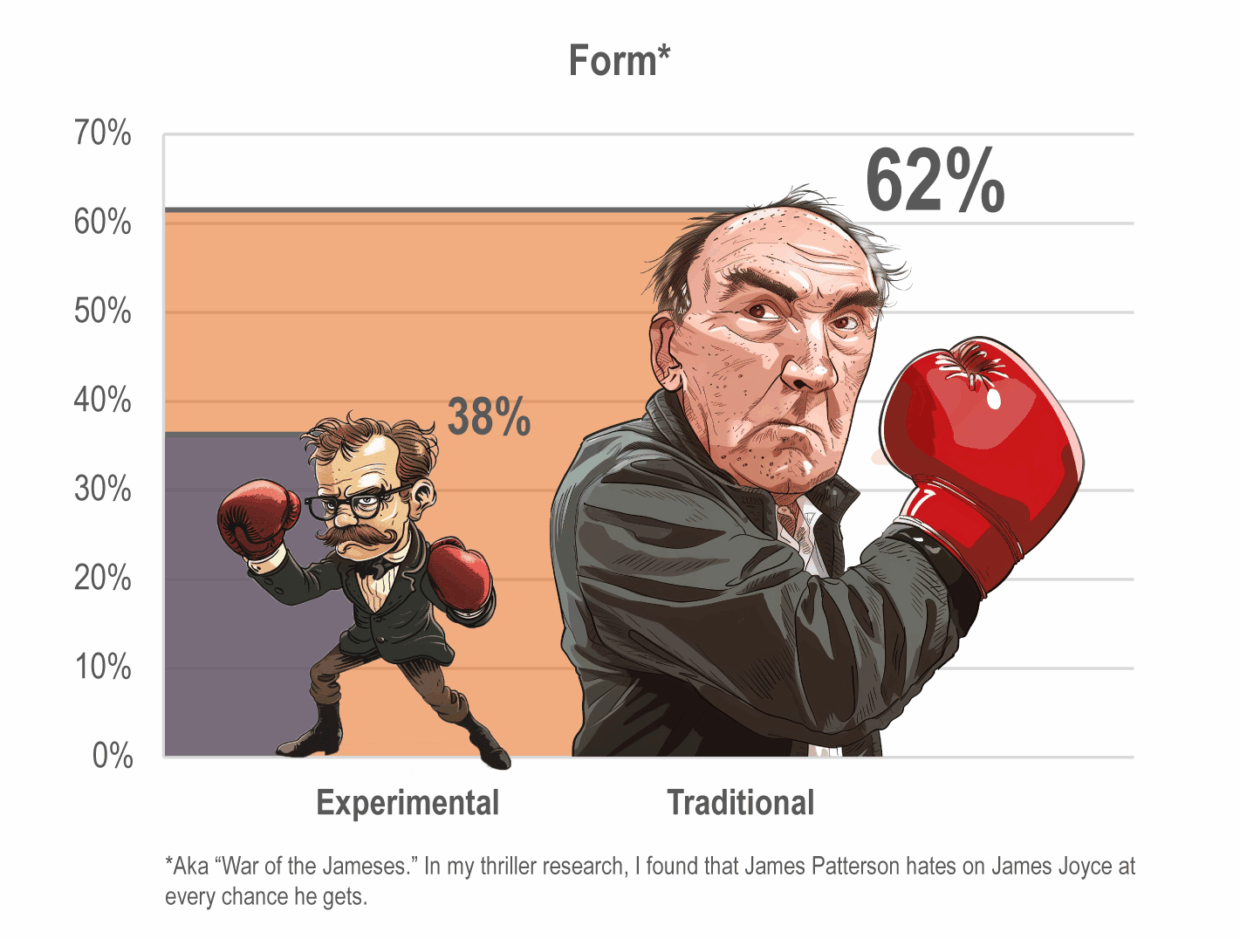

Form: Traditional (62%)

Mood/tone: Mysterious (35%), tense (21%), philosophical (18%)

Characters

Number of main characters: 3–5 (60%)

Age: Adult (60%)

Class: Working class (38%), middle class (32%)

Gender: No preference (54%), cis female (25%)

Sexuality: No preference (51%), straight (40%)

Race or ethnicity: No preference (92%)

Morals: Good (54%)

Story

Duration: No preference (47%)

How the main characters spend their time: Falling in or out of love (19%); participating in criminal activity (16%), particularly murder; being creative (14%), particularly in writing; and helping others (10%), particularly operating as a spiritual leader.

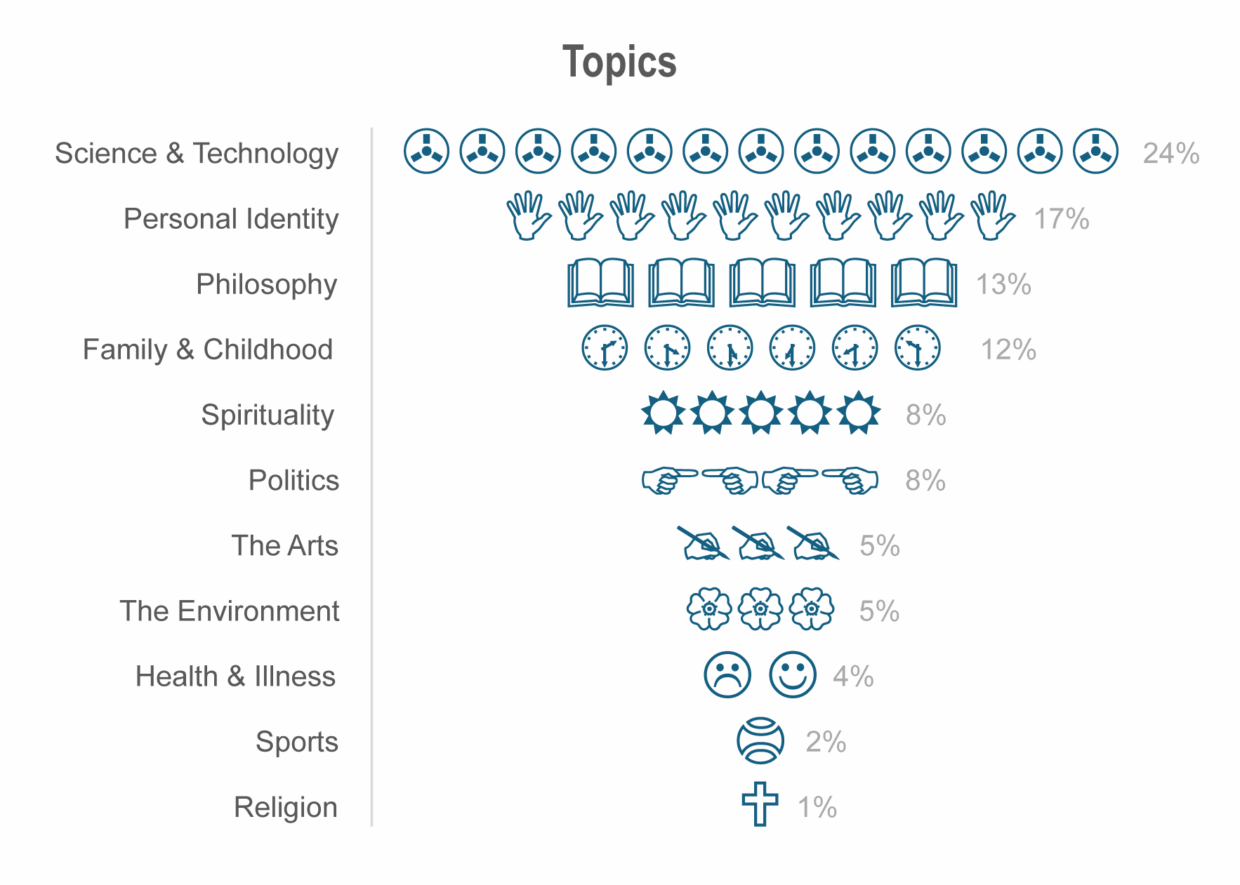

Topics: Science & technology (24%), particularly good vs. evil, new technology, advanced science, and the workings of the universe.

Setting: Large cities (31%)

Dialogue: A moderate amount (60%)

Descriptions: Long (54%)

Sexual content: A little (37%)

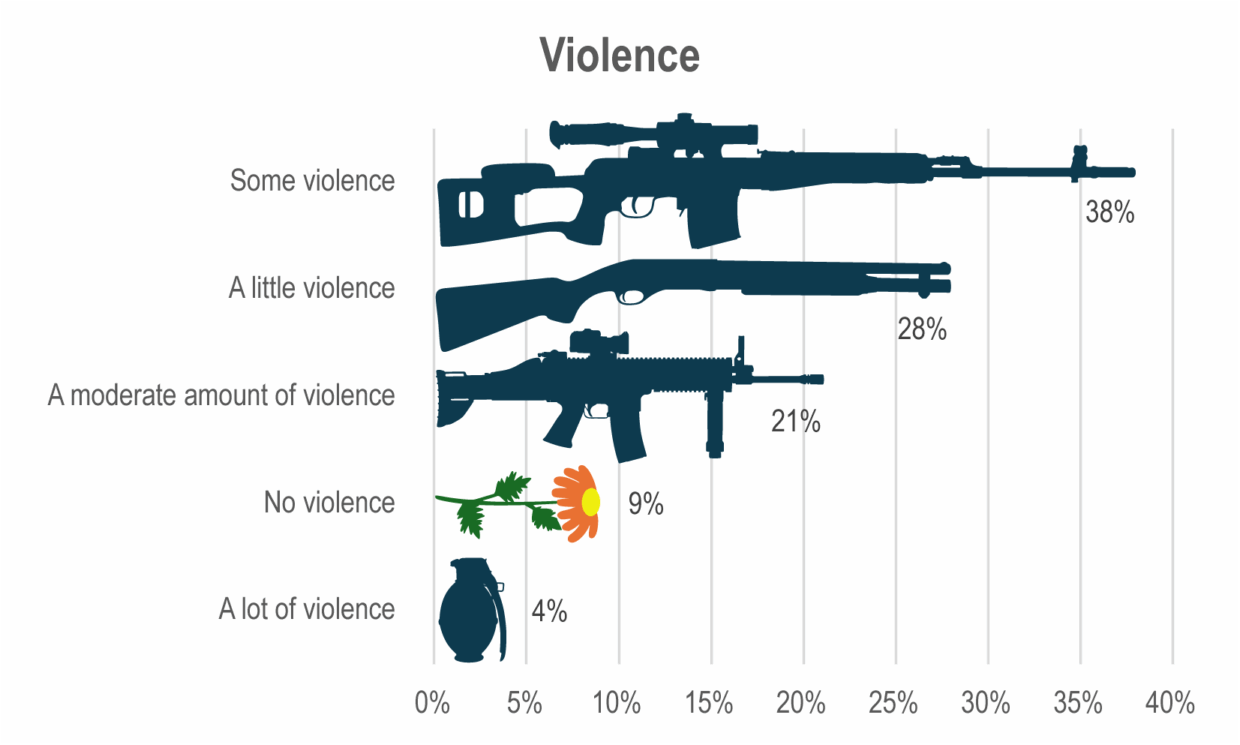

Violence: Some violence (38%)

Ending: Resolved (57%)

The Most Unwanted Novel

General

Genre: Romance (37%), Horror (20%), Classic Literature (12%) and Historical Fiction (12%)

Length: More than 500 pages (8%)

Perspective: Second person (2%)

Tense: Present Tense (33%)

Storytelling technique: Epistolary (3%), stream of consciousness (11%), stories within stories (24%).

Style: Unrealistic (26%), featuring different planets, talking animals, extraterrestrials, and sentient robots

Form: Experimental (38%), with chapters that read like long encyclopedia entries,

long, meandering sentences, and moments where the author comments on the art of writing

Mood/tone: Sad (2%), calm (5%), happy (8%), playful (9%)

Characters

Number of main characters: 9–11 (3%)

Age: Old age (0%) and childhood (0%)

Class: Aristocratic (3%)

Gender: Transgender (0%), nonbinary (2%), cis man (17%)

Sexuality: Other (0%)

Race or ethnicity: Non-American and fantastical beings (0%)

Morals: Bad (46%)

Story

Duration: One day (0%)

How the main characters spend their time: Playing a sport (1%), specifically tennis; farming or living off the land (5%), specifically fishing.

Topics: Religion (0%), sports (2%), health and fitness (4%), the environment (5%), the arts (5%), and politics (8%).

Setting: Rural area (9%) and natural setting (18%), specifically a polar region

Dialogue: A little (0%)

Descriptions: Short (46%)

Sexual content: A lot (4%)

Violence: A lot (4%)

Ending: Unresolved (41%)

Many of these results will be unsurprising if you pay any attention to bestseller lists (synonymous with most-wanted book lists, in my mind): “Thriller or mystery” was the most wanted genre. Americans preferred traditional, realistic narratives over the experimental and unreal. They wanted medium-size books (200–300 pages) over very long or very short ones (under 200 and over 500 tied for last place).

These results line up almost exactly with research presented by Jodie Archer and Mathew Jockers in their book The Bestseller Code, an algorithmic study of what makes a book a bestseller. Creating a computer program to read and analyze 500 books from New York Times bestseller lists, Archer and Jockers sought to identify the specific components—down to themes and diction—that make a book more likely to appear on this highly coveted list. Their program found several similar patterns to our poll: People want stories told in the third person, working-class characters, and stories set in large cities on Earth. Also in keeping with our data, they found that people are less inclined to read about imaginary creatures—especially sentient robots and talking animals. But most striking was how closely our data lined up with the novel that Archer and Jockers’s algorithm declared as the ultimate bestselling novel, a novel that the data showed had the perfect balance of everything readers want: Dave Eggers’s The Circle.

Both The Circle and The Most Wanted Novel are thrillers about an adult white woman from a working-class background who struggles against an advanced form of technology. Both books are told in the third-person past tense, and both take place over the course of a few months. Both involve a character struggling against some aspect of society (in each case it’s technology’s encroachment on our lives). Both involve murder and interweave a love story into the techno-thriller drama.

Even with this validation, there are several survey results that might give you pause. For one, there’s a glaring contradiction in responses to two answers. The most wanted activity for characters to experience in a novel was “falling in or out of love,” but the most unwanted genre was romance. Given the popularity of romance novels, it’s hard to square this until you consider their place in culture, with romance often seen as a form of women’s literature, a category that historically has not been given as much weight and respect as literature written by cis men.

Several people have also expressed surprise at historical fiction’s “unwantedness” in the poll results. Surely these books are also widely popular, with many dedicated and loyal readers. (Ditto horror and classic literature, the other two unpopular genres in the poll.) To understand this phenomenon, we might consider another finding of The Bestseller Code: that people by and large prefer reading about everyday people living everyday lives—until the stirring events of the novel begin, of course. Jockers and Archer essentially showed that more often than not readers are drawn to stories about themselves set in the times they are living.

From Data to Fiction

Almost all my books use “literary constraints,” an approach to writing popularized by the French avant-garde group the Oulipo, whose members adopt nontraditional rules or guidelines to write original, and often surprising, works of literature. In the case of People’s Choice Literature, I used each polling data point as well as machine learning data from The Bestseller Code (which provided minutiae that a public opinion poll, due to poll fatigue factors, could never measure) as a constraint for each novel. After collecting the data and parsing it into two groups of wanted and unwanted qualities, I then studied these groups, looking for patterns and connections between data points that might suggest characterization, specific settings, and so on. To give an example, while considering the poll results for desired character activities, it didn’t take long to see that the main characters of The Most Wanted needed to:

Fall in or out of love

Commit a crime (specifically murder)

Be creative (as a writer)

Help others (by being a spiritual leader)

This data, combined with other poll findings—like the fact that science and technology (specifically questions of good versus evil and new technology) was the most wanted topic and that people want to read about the working class—led to a story about a lovesick woman (25% prefer cis female protagonists) from a working class background finding herself in the middle of a criminal conspiracy in Silicon Valley. Another author might have distributed these characteristics in different ways. From my perspective, it made sense for the protagonist, Alix Finn, to find herself in the middle of both a mysterious crime and the pangs of new love. And, given the tech world’s notorious blending of leftist, spiritual aesthetics with big business, it seemed natural to combine technology and spiritualism into a single character, D. J. Wylde.

Even with all these constraints, I realized only after conducting the poll that the 76 answers and the 100-or-so data points offered by The Bestseller Code would not provide enough guidance to fill the hundreds of pages that the data had called for. Of course, I could have gotten creative and filled in all the blanks with my own ideas, but given that this project sought to engage with the tastes of an entire nation, it seemed important to make these novels less about my creative impulses and more about, well, what people want and don’t want.

In both books, I accomplished this in two different ways. In The Most Wanted Novel, I relied on personal research into the thriller tradition (i.e., reading dozens of blockbuster thrillers and taking MasterClass courses by Dan Brown and James Patterson). For The Most Unwanted, I leaned on answers to an open-ended question I hadn’t thought much of while writing the poll: “If you had unlimited resources and could commission your favorite author to write a novel just for you, what would it be about?”

While we may live in our digital bubbles today, American taste in literature is largely just as centralized and normalized as before the internet invaded our lives.

The majority of these answers fell on genre lines—like “sci-fi thriller” or “Horror Mystery Thriller”—and revealed no new information that I hadn’t already learned from the poll’s four genre questions. But a fraction of respondents gave more specific, idiosyncratic answers to this open question, such as “Jay-Z writes my biography” and “the ramifications of the American political system on global social structures.” The more I read these answers, the more I realized they were just what would give this unwanted novel the depth and texture it needed. And because each of these open-ended answers was unique, representing a single perspective (or 0.1% of survey respondents), they seemed a perfect fit for this novel of uncommon and less-desired characteristics. Here is an inexhaustive list of the open-ended answers I used in The Most Unwanted Novel, presented in the order they appear in the story:

“It would be a simple romance novel, maybe holiday themed. Where two strangers, a man and woman, are having a tough time during the holiday season due to a tragedy that occurred around that time years ago…”

“It would likely be about Elves that are forced into hiding among humans. Having to conceal their identities and their magic all while of course being hunted by both elves and humans alike…”

“humans settling on Mars”

“Fishing”

“Probably something involving cats, how they take over the world, and especially get rid of this useless government we have”

“Pirates”

“Sports Talk Radio”

“I would like it to be about the Middle Ages and how the tyranny of a king made him collapse a kingdom.”

“the human mind and its workings”

“It would be a historical fiction work after the founding of America.”

“…perhaps a mystery, set in Imperial Rome during the time of Marcus Aurelius.”

“HISTORY OF FRANK SINATRA”

“The mafia”

“werewolves”

“Nephilim”

“A queer horror novel where it’s a group of pro tags in a found-family community making life work on a commune, but also folkloric creatures of some sort complicate matters…Happy ending queer horror!!!”

“It would be about the secrets to success with hobbies”

“It would be a sci-fi space opera with diverse characters who are queer and trans that has…plain language mixed with some highly poetic styles.”

“Probably a love triangle romance with a tiny bit of smut.”

“something to do with nietzsche”

People’s Choice Literature

So, what are we to make of all this? What do the data and these novels reveal about this elusive “American imagination” mentioned earlier? Sure, we have a techno-thriller on the one hand and an experimental goulash of genres and styles on the other, but what do these books reveal not only about literary tastes (and distastes) but our culture at large? Each novel has a strong technological element, something likely indicative of the ubiquity of technology in our lives—a force so pervasive we cannot imagine a future without it. And each novel features one or dozens of love stories—an indication of our complicated relationship with the idea of love. But where these novels differ is where things get particularly interesting.

One therapist friend suggested that this book exemplifies the Jungian notions of the persona and the shadow. These terms describe that part of an individual’s psyche that is presented to the world (the persona) and that part that is seen as undesirable and therefore hidden (the shadow). If we think of culture as a body, then The Most Wanted Novel would be the persona, made up of the most visible and widely accepted parts—the façade. The Most Unwanted Novel would then be the shadow, those aspects of the cultural body often hidden or pushed to the side but inextricably part of the whole. Notably, the shadow contains those things that we repress in ourselves, things that no matter how hard we try to sideline are still part of us and will fight hard to see the light of day. In the case of The Most Unwanted, nearly every character has an unidentifiable, queer sexuality, and many are nonbinary or transgender—qualities that, of course, were directed by the poll results and that are unsurprising in a country that introduced over 510 anti-LGBTQ bills into state legislatures in 2023 and who voted against the supposedly pro-transgender presidential candidate in 2024.

This book also seems to validate what People’s Choice Music revealed back in 1996: that while we may live in our digital bubbles today, American taste in literature is largely just as centralized and normalized as before the internet invaded our lives. The majority of respondents pointed to a most-wanted book that veered little from the kind of fiction that appears in airports, pharmacies, and Target. Most respondents ran as quickly to the middle as publishers want them to, asking for the same story they’ve consumed countless times. In this way, The Most Wanted performs the cultural loop we cannot seem to get out of—a circuit so closed that variation on time-tested styles, narrative forms, and subjects is rarely an option.

As for The Most Unwanted, it won’t take readers long to see just how different that novel is from most fiction they’re used to reading. One early reader described it “as if César Aira, Kathy Acker, and Philip K. Dick got high and tried to write Tristram Shandy.” But if we look closer at the world that the unwanted data pointed to—a colonized Mars populated by the ultrawealthy and their attendant androids after Earth becomes uninhabitable—it’s not hard to see how this picture squares with the space colonization ambitions of some of today’s most notorious billionaires. Which is to say, while they may look forward to this future, it seems the vast majority of people do not.

But enough about my interpretations. The novels are done, soon to be printed, epub’d, and available for dissection, meditation, and most importantly, judgment. They are each infused with years of writing and editing in an earnest attempt, in each case, to win you over. The critics will have their say. The publishers will study the sales figures to decide if similar books will ever see the light of day. But for now, it won’t be the critics or publishers who will decide which is the better novel; it’s you. Perhaps you’ll love one book and hate the other. Maybe you’ll find pleasure in a genre you never thought you would. And maybe, just maybe, you might find yourself enjoying parts—or all—of both.

__________________________________

People’s Choice Literature: The Most Wanted and Unwanted Novels by Tom Comitta is available from Columbia University Press.

Tom Comitta

Tom Comitta is the author of two novels, The Nature Book and Patchwork. Their short fiction and essays have appeared in Wired, Literary Hub, Electric Literature, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and Bomb.