What Did You Read This Year

That You Loved?

Freeman's Contributors Weigh In on Their Favorite Books of 2020

2020 was a hard year for reading—it was a hard for so many things. Like wearing clothes some days. Or bathing. Or saying goodbye, or trying to mourn. It was a hard year for voting in public or for living with someone you love.

It was a hard year in which to believe in the possibilities of a fellow human.

And yet, as with so many of these essential tasks—well, perhaps not always bathing—we found ways to get it done. Even when powerful people tried to stop us, or the weight of what happened this year (and all that led up to it), piled on people.

What seemed like a year in which reading would stop turned into an explosion of reading. People turned to their shelves and cooked their way through cookbooks, read their way through novels bought years ago. Poetry readings ended up with crowds of hundreds because anyone could dial in. Book clubs for great classics kicked off and did brilliantly.

Normally when I write to Freeman’s contributors to ask what they read this year and loved—any book, not just new ones—I get a handful of responses. I need to chase. This year an avalanche of suggestions and enthusiasm was unleashed. Here’s the drift: there are great books out there, and they kept these writers sustained, engaged, sane, in pleasure—and less alone.

–John Freeman

*

2020 is the year when I discovered the joy of reading with other people. I had always been a solitary reader, but reading War and Peace, during the early months of the pandemic, with three thousand readers around the world for A Public Space’s Tolstoy Together was an extraordinarily sustaining experience. Since the spring, I’ve also been in a two-person book club with Edmund White, and we’ve been skyping every evening to talk about the day’s reading. One of the highlights was The Collected Stories of Elizabeth Bowen. We marveled at her sentences, puzzled at words we didn’t know, and relished the stories, sometimes taking turns to read aloud to each other.

–Yiyun Li, author of Must I Go

Ever since I was a child, I’ve been searching for questions. Not the comfortable sort of questions that make me feel good, but the questions I find inconvenient, that are sometimes hurtful, that destroy the foundations of my inner structure and undermine the very depths of my world. I was drawn to The Schooldays of Jesus, by J.M. Coetzee as it felt full of these kinds of questions. Whenever I want to destroy the world in my head in order to discover an invisible truth, I am sure I will pick up this book again.

–Sayaka Murata (trans. Ginny Tapley Takemori), author of Earthlings

A couple months ago I read The Copenhagen Trilogy by Tove Ditlevsen, a Danish writer who has been dead almost 50 years, but her books are being given new life in English. The UK edition of this trilogy had been sitting on my shelf for almost a year, in three slim ice-cream-pink editions, “Childhood,” “Youth,” and the ominous, if precisely titled, “Dependency.” How could I have let these precious volumes just sit there, dormant?

One night I began to read them in order, one book per evening. They are each brief and riveting. Tove Ditlevsen has skills that come along a few times a century. She understands perfectly how to do the simplest thing that is also the most difficult thing: tell a story. She knows just how to configure the torment and life-force of a real-seeming person into a book. I don’t mean the author. I mean the character. Every childhood has a smell, she writes. Indeed. You know it when you’re a child, and also that only you can smell it. She goes to work in the second book, and instantly understands the nature of work, because she’s smart, this character, in an earthy and credible way: “I was someone whose physical strength they’d bought for a certain number of hours each day. They didn’t care about the rest of me.” The rest of her wants to be a writer. Becomes one, but slowly. First, there are all the days spent toiling for money and the nights guzzling booze with people you don’t even like, so that you can try to find a lover. “You have to get through it,” she says of youth, “it has no other meaning.” Book three, “Dependency,” is brutal and quick. She’s a successful writer. Her life speeds up to a hurtling pace, only to stop on a dime, on a needle. Not as destiny, but something more like chance. She passes through the needle’s eye. Looks back, sees us, her reader, and communicates only that she can’t return to the world she’s left behind. She’s an addict.

–Rachel Kushner, author of the The Mayor of Leipzig and The Hard Crowd: Essays 2000-2020, forthcoming from Karma Books and Scribner in 2021

It’s seemed a year for notebooks, diaries, travelogues and catalogues of one kind or another—W.G. Sebald, Anne Carson, Annie Dillard, Franz Kafka, Derek Jarman, Beverley Farmer. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s wide-roving journeys via moss (Gathering Moss). Werner Herzog traveling on foot from Munich to Paris in a 1974 pilgrimage to reach his mentor Lotte Eisner; breaking into holiday cabins for shelter along the way, contemplating friendship with field mice, living mainly on tangerines and milk (Of Walking In Ice).

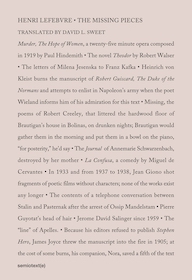

At one point—perhaps the darkest, during the shortest and most insular days of Melbourne’s stringent winter lockdown—I rediscovered a strange (fatalistic?) comfort in Henri Lefebvre’s The Missing Pieces (trans. David L. Sweet), an inventory of great works lost or destroyed or never completed: The journals of Annemarie Schwarzenbach, destroyed by her mother … The man Peter Handke … The sixteen drawings offered by Amadeo Modigliani to his lover Anna Akhmatova were “smoked” by the Red Guards, who used them as cigarette paper. The inscription on the flyleaf is from my former husband, years ago. It reads: To all the great things ahead. Finished and otherwise, all worthwhile.

–Josephine Rowe, author of A Loving, Faithful Animal and Here Until August

When the pandemic started I could not read at all, it was like the imagination switch was off (and of course you need it on for reading and writing). So when I could start it was re-reads and poetry mostly. And I think my fave was The Beauty of The Husband by Anne Carson. I really can’t say much about it: it’s gorgeous and also it’s dedicated to Keats whom I’m obsessed with and it made me want to read and write again, which I didn’t really with any method but at least broke the spell of just being still.

–Mariana Enriquez, author of The Dangers of Smoking in Bed, translated by Megan McDowell (January 2021)

In a rich and varied diet of reading, this year, I seem to have wandered through several different categories of books. These have included appraisals of our current situation such as Bill McKibben’s deeply frightening Falter and Louise Aronson’s Elderhood, a description, from inside, of our country’s inadequate approach to elder health care. For personal memoir, there has been Lost Property, an outrageous yet captivating account by the well-read, whip-smart rich playboy turned publisher Ben Sonnenberg; and, starkly contrasting in tone and character, mystery writer Henning Mankell’s Quicksand, a sharply perceptive and moving meditation on life, death, his own fatal illness, our devastation of the planet. Doses of fiction, mostly from decades past, happily took me far away from the present catastrophes: James Agee’s wonderful A Death in the Family, for the second time; yet another from my row of Virago editions of Elizabeth Taylor’s always well written and engrossing novels, this one In a Summer Season; and, by Patrick Hamilton (author of Hangover Square), the poorly titled but very well done tale of a WWII boarding house, Slaves of Solitude. Finally, I have also been continuing through Lynne Tillman’s most recent, which, like much of her fiction, so deftly straddles the genres. Men and Apparitions tells a fully human story while miraculously feeding one’s mind with the complex narrator’s observations about childhood, family, photography and representation, self and self-understanding, culture, and the art and fallibility of seeing.

–Lydia Davis, author of Essays Two, forthcoming in November 2021 (Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

When the pandemic hit, my body felt differently, some days more than others. My shoulders tense up, constant headaches, my left leg has knots up and down it, my gut has been acting up. For years, friends and therapists recommended The Body Keeps The Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. With a title like that, it felt too close to home and I wasn’t ready to face what I was afraid I’d find in the pages. These past months, the book has helped explain so much about the traumas that are stored in my body, from childhood, from crossing the border, from living undocumented in this country, all of them have bubbled up during this pandemic. Similarly, Roberto Lovato’s Unforgetting: A Memoir of Family, Migration, Gangs, and Revolution in the Americas, has helped explain the everlasting question: “why is my family in this country?” His account of his family’s migration is tied to the historical moments that mark every Salvadoran: the 1932 massacre, the civil war, and our current “gang problem.” These two books are helping me in my healing journey.

–Javier Zamora, author of Unaccompanied

A book I constantly reread is William Kentridge’s Six Drawing Lessons, his Charles Eliot Norton lectures published in 2014. In it he is trying every way he can to name the place where the fresh bubbles up, the new fights through, and show what a delicate repeated miracle that is. It is stumbley or however you’d spell that in just the right ways. And of course massively illustrated.

–Kay Ryan, author of Synthesizing Gravity: Selected Prose

I loved Aminatta Forna’s upcoming The Window Seat, a collection of essays of insatiable curiosity and enviable experience, endowed with a moral compass of great precision. They’re terribly entertaining to boot. This is the book of somebody who pays attention to the world and, like a great guide, makes us notice what we’d miss without her.

–Juan Gabriel Vasquez, author of The Shape of the Ruins, translated by Anne McLean

Well, the best book I read hasn’t been published in English yet, and that is Semezdin Mehmedinović’s My Heart (Catapult, March 2021), which I read in Bosnian (as Me’med, crvena bandana i pahuljica) and then in translation, and it is a marvel of thoughtfulness and love. Another Bosnian book I loved is Catch the Rabbit (Uhvati zeca), by Lana Bastašić, the winner of the 2020 European Union Prize for Literature. It’s coming out in English this summer. Lana Bastašić’s novel of two young women plunging into post-war Bosnia like two Alices into Wonderland is smart, energetic, passionate, announcing a major talent.

–Aleksandar Hemon, author of This Does Not Belong To You/My Parents: An Introduction

The most gripping book I read this year was Fate is the Hunter (1961), Ernest K. Gann’s classic (but still insufficiently appreciated) account of his life as a pilot in the early and dangerous days of civil aviation. He shares with Len Deighton the ability to convey detailed technical information with no loss of narrative power.

–Geoff Dyer, author of Broadsword Calling Danny Boy: Watching Where Eagles Dare

Afterlives by Abdulrazak Gurnah saved me from a long reading slump. I have always been a fan of his work and this latest novel is a treat with its effortless storytelling, vivid East African setting and insight into German colonialism. Gurnah excels at depicting the lives of those made small by cruelty and injustice, those who look away rather than confront, the cowed and put-upon. This is why in his hands humiliated women, abused orphans and aspiring refugees are rendered so believable and within reach. Seductive too is the beautiful, harsh world he depicts of bitter-sweet encounters and pockets of compassion, twists of fate and fluctuating fortunes. As I turned the pages, I forgot I was reading fiction, it felt so real.

–Leila Aboulela author of Bird Summons

But the mere thought of Mann’s 1,500-page tetralogy Joseph and His Brothers—a retelling of Genesis 27-50 (Jacob; Joseph’s youth; Joseph in Egypt; his reunion with his family), written between 1926 and 1943—had always intimidated me. (And, from what I can tell, many others, even Mann fanatics: although he considered “Joseph” his greatest work, it has failed to enter the literary current here the way the other big novels have.) How wrong I was. As with other great works of historical fiction (Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian comes to mind), this one uses a brilliantly vivid reimagining of a historical moment—Mann shrewdly places Joseph’s story during the reign of Akhnaton, the monotheist Pharaoh—as the armature for profound philosophical reflections: in this case, about the nature of religion and myth and the cyclical nature of human experience, both individual and collective. In John E. Woods’s lucid recent translation, this masterwork takes on a startling, gratifying freshness.

–Daniel Mendelsohn, author of Three Rings: A Tale of Exile Narrative and Fate

I read the prize-winning book, Everything Man: The Form and Function of Paul Robeson by Shana Redmond. It is both a meticulously researched exploration/celebration of Paul Roberson’s dynamic contribution to American music, art, sound, aesthetics; but equally important, the book braids this view with Robeson’s unique contribution to abolitionism, independence, and liberation worldwide.

–Robin Coste Lewis, author of Voyage of the Sable Venus: And Other Poems

I’d like to recommend Rachel Cohen’s Austen Years: A Memoir in Five Novels. Cohen, a beautiful writer, also has an extremely interesting mind: precise, patient, thoughtful, probing. For me, in this ghastly year, literature—not only this book but many others—has been my salvation. Cohen’s memoir, about the intense years of her children’s births and her father’s death, is also about reading Jane Austen, about the interweaving of Austen’s life with her own, about how the wisdom of those novels and their creator became inseparably a part of Cohen’s own transformative experiences. As Louise Glück writes, in “October,” “you are not alone, / the poem said, / in the dark tunnel.” Words (thank goodness) to live by.

–Claire Messud, author of Kant’s Little Prussian Head and Other Reasons Why I Write: An Autobiography in Essays

Snake Poems: An Aztec Invocation (Reprint, Arizona University Press, 2019) by late, gay poet, Francisco X. Alarcón, presents a new idea in Latinx poetics—re-framing the metaphysics of the ancient Mexicas colonized by Spain in the early 1500s. Alarcón retrieves and repositions Spanish Priest Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón’s (Francisco saw this man as a fictive relative) ethnographic research into the spells, ritual songs, chants and stories of the Mexica. Here Alarcón creates a chorus and responds to and with the Mexica’s voices, heightened callings, transpositions of contemporary and hemispheric sources of knowledge.

–Juan Felipe Herrera, author of Everyday We Get More Illegal

Poetry, ideals, and creative work are not mere substitutes or metaphors for the substance of our lives. They can literally make it impossible to move, or just as easily make us take a breath. How do words engage like this with our existence? When we are steeped in sadness, with no relief in sight, how is it that words can engage with our memories and our love? In words that only Yiyun Li could have composed, Where Reasons End delves deep into the quiet reaches of these questions. An unforgettable novel.

–Mieko Kawakami (translated by Sam Bett), author of Breasts and Eggs: A Novel, translated by Sam Bett and David Boyd

Recalling its slow, restless intensity, I was rereading Forrest Gander’s Pulitzer Prize-winning poetry collection Be With recently for patterns of feeling that might help me cope with the tremendous loss of life due to Covid in the Black community in particular, a tragedy worsened by the history of racism in America.

–Gregory Pardlo, author of Air Traffic: A Memoir of Ambition and Manhood in America

I just loved Wilding, Isabella Tree’s account of her and her husband’s decision to return their farm to nature and which she uses as a lens to view the past and future of the environmental crisis, made all the more devastating for the utter absence of hyperbole, Tree’s measured tone and the courage of the couple’s convictions.

–Aminatta Forna, author of The Window Seat, forthcoming May 2021 (Grove)

This year, I found Jorge Luis Borges to be the ultimate escapism. Borges: Esplendor y derrota by María Esther Vázquez is a powerful, divinely written biographical work about him and his ideas, and strangely it’s only available in Spanish. Meanwhile Borges, penned by Borges’ best friend and collaborator Bioy Casares, is a massive brick of genius, where Borges voice lives again in all it’s wickedness and joy, unconstrained by Borges’ own prudence and obsession with form. Bioy Casares’s Borges has saved me many times this year, and it’s blissful to know that Valerie Miles is at work translating it and will be soon coming to American readers, to rock their world, too. Peeking into other writers’ lives became a pill-popper: I devoured Sontag: Her Life and Work by Benjamin Moser, and I’m currently fascinated with Inside Story by Martin Amis.

–Pola Oloixorac, author of Mona: A Novel, translated by Adam Morris, forthcoming March 2021 (Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

Geoffroy de Lagasnerie’s Judge and Punish: The Penal State on Trial (Stanford University Press) is an extremely powerful book on the way the penal system reproduces and amplify violence instead of undoing it, on how the juridical institutions are almost never a source of help for the victims but rather a place of victimization and of perpetuation of the most common social pulsions—racism, homophobia, classism. This book is really a classic for the new generation, and a radical manifesto to reshape our minds.

–Édouard Louis, author of Who Killed My Father, translated by Lorin Stein, and Dialogue sur l’art et la politique, with Ken Loach, forthcoming in March from Puf and in April from Seuil, Combats et métamorphoses d’une femme

I re-read Tayeb Salih’s Season of Migration to the North recently for a course I taught. Published in 1967 in Arabic, the novel has become a classic of postcolonial literature for a reason. It tells the story of Mustafa Sa’eed, a mysterious Sudanese man who is sent to England to study in the 1920s. In London, he commences a series of destructive relationships with English women—ostensibly in revenge for British colonialism of the Sudan. Told by a narrator who recounts Sa’eed’s story, the slim novel reads like a prose-poem of incredible power and beauty. Colonialism, gender violence, heap loads of Freud, and the Nile river all in one stunning package.

–Fatin Abbas, author of The Interventionists, forthcoming from W.W. Norton

There comes a point, maybe, at which you realize you’ve sung the praises of a book to so many people that it is becoming obscene—and yet, here I am, once again recommending Lost Children Archive, by Valeria Luiselli. A quick diary check has confirmed that I did indeed read it this year—the first week of January—and not in fact, as it now feels, a different life ago. However, its themes of loss and banishment —personal and state-sponsored—and the nuanced difference between alone together and together alone are more pertinent now than they were in that different lifetime a year ago when I first read the novel.

–Ross Raisin, author of A Natural and Read This If You Want to Be A Great Writer

The lost objects and extinct creatures catalogued in Judith Schalansky’s An Inventory of Losses will forever be remembered, now that their stories have been embalmed in her enviably well written prose. It is a book of our times and for our time; hopeful in its beautiful creation while admitting to the melancholy knowing that the beauty of art meets its match in material destruction. An Inventory of Losses is pure gold storytelling, excellently brought into English from German by Jackie Smith.

–Sjón, author of Red Milk: A Novel, translated by Victoria Cribb, forthcoming in 2021

Gunnhild Øyehaug is one of Norway’s finest writers and her latest collection of short stories shows her at her absolute best. Entitled Vonde blomar (meaning “Evil Flowers” and yes, there’s a link to Baudelaire here), clocking in at a mere 99 pages plus starting with this brilliant, no holds barred opening, “As I sat on the toilet menstruating, a pretty large piece of my brain fell into the bowl” (my translation here), what’s not to like? These stories are not only good, or brilliant, or expertly written, they also comment on each other; stories will object and protest furiously to other stories just told, narrators comments their own text, stops to digress or simply wonder and if it does sound confusing, it’s not. It’s so well done, playful and fun and experimental; it’s smart and a weekend in cloud cuckoo land, it’s punk and pure beauty and more than that, it is one of those, “damn, I wish I could write like that” and the feeling of relief that at least she’s able to. The book will be published in the US by Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

–Johan Harstad, author of Ferskenen, forthcoming from Open Letters

Coincidentally, the two novels that most absorbed me in this distracting reading year were both written by Norwegians. Long Live the Post Horn by Vigdis Hjorth (published in English in 2020, translation by Charlotte Barslund) had me caring about a marketing campaign for the Norwegian Postal Workers’ Union—it’s funny, wry, insightful, and finally sincere. The Unseen by Roy Jacobsen (published in English in 2016, translation by Don Bartlett and Don Shaw) describes the life of a family living on a remote Norwegian island in the early 20th century, and is a masterpiece of accumulated effects. Both novels are testaments to the human connection to be found in ordinary daily rhythms—a moving reminder in this lonely year.

–Fiona McFarlane, author The High Places: Stories

Not actually out in the world until January 2021, but I read a proof of Daniel Loedel’s Hades, Argentina early in 2020 and remain its grip all these months later. It’s a novel about the impossibility of leaving certain places and people behind (because what you’re really trying and failing to leave behind is yourself). Loedel uses myth, history and imagination to produce a work of great complexity—although set in Argentina it speaks to so many nations’ brutal histories, some past, some still unfolding.

–Kamila Shamsie, author of Home Fire

Rye Curtis’s Kingdomtide is one of the best first novels I’ve ever read: gothic and crazy, tender, grotesque, comic, and deeply humane—a dizzying range of notes for a single book to strike, much less a debut. The novel is a riveting tale of wilderness survival powered by the irresistible voice of a woman in her eighties (deemed persuasive and compelling by my two beloved relatives who meet that description), an achievement all the more remarkable for a young male author. Rye Curtis is a wonder, and Kingdomtide deserves an enormous readership.

–Jennifer Egan, author of Manhattan Beach

The Cost of Living by Deborah Levy was a book I kept close at hand this year. It’s intelligent, funny, gorgeously written, and subtly offers lessons on how to live boldly as a woman and an artist. I also loved Brown Album: Essays on Exile and Identity by Porochista Khakpour. It’s a book that embraces complexity and bewilderment, that grapples more than it guides. It seems strange to characterize a book of essays as a page-turner, but that was my experience of reading Brown Album. I just had to know where her mind would go next.

–Tania James, author of The Tusk That Did the Damage

One of the best books I read this year was Sharks in the Time of Saviors by Kawai Strong Washburn. It came out in early March which makes it feel like it came out last year or a generation ago, but it’s really stayed with me even through all this change and interminable stagnancy. As good a debut as I have ever read.

–Tommy Orange, author of There, There

Julia Alvarez’s Afterlife is such a compact, resonant novel. It starts with the loneliness of beginning the rest of one’s life after the death of a partner and ends with the affirmation and necessity of our human connections. Antonia, the retired literature professor at the center of this wonderful novel, finds that the privacy of her grief is no match for the ongoing and overwhelming need in the world. Soon, she’s dealing with a missing sister, while also contemplating just how much she can help in protecting a pregnant, undocumented young woman. Afterlife candidly confronts what it means when our individual sorrow might shield us from the ongoing troubles of the world, yet also reminds us of the solace in connecting and being with others. To Antonia’s surprise—and maybe ours as well—sometimes sifting through the old lessons of literature shows us that the urgent and poignant questions of living have been answered so many times by the wonder of the page itself.

–Manuel Muñoz, author of What You See in the Dark

The exasperation, warmth, honesty, and complete lack of distance in Karla Cornejo Villavicencio’s The Undocumented Americans made me feel like I was seeing someone take apart and rebuild the art of journalism. From the tough investigative interviews with undocumented Americans like the crews who helped clean up the World Trade Center site, to Villavicencio’s wild descriptions of the dreams that she has while reporting, this book was pure empathetic magic.

–HR Smith, writer and editor at Sierra Magazine

Serge Pey’s The Treasure of the Spanish Civil War (translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith): I read the opening six page story, “An Execution” and knew immediately I’d found a book I was hungry for. I read the second story, “The Washing and the Clothesline” and thought, this seven page story borders on a masterpiece, and knew then to slow down and savor what was still to come.

MAP: Collected and Last Poems by Wislawa Szymborska (Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh, translators.) This book, if read from start to finish, captures the drama and conveys the experience of a poet discovering an original voice and vision that will enable her work to rise to the level of genius.

–Stuart Dybek, author of Ecstatic Cahoots

Two books shook me this year in particular. It’s Me, Eddie, a fictional memoir (1979) by Eduard Limonov. Beyond the delusional, transgressive and sick story about the end of his marriage on the streets of an unrecognizable New York, Limonov talks about the despair and sadness that the most brutal capitalism engendered from the perspective of a very poor Russian immigrant, so unbearably narcissistic as funny and profane.

The other is The Notebook (1987) by the Hungarian Ágota Kristóf. With sharp phrases that seem to have been used for the first time, Kristóf—an immigrant in Switzerland—tells the story of Claus and Lucas, two merciless twins and their grandmother, known as The Witch. The twins, extremely clever and far from any moral consideration, fight to survive during the Second World War through small experiments or exercises, as they call them. They starve for days, stop talking for weeks, or whip each other until they bleed, among many other things. They are alone but they are together in an occupied land. An army of two.

In an increasingly politically correct world, where many writers are their own censorship machines fearful of what their potential fans, not readers, may think of them, these two works remind us that the truth of the books lives entirely in their pages, outside of them there are only speculations, vain complaints and self-complacency.

–Andrés Felipe Solano, author of Los días de la fiebre (Days of the fever)

This year the best was James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time. The prophetic cadence of the queer preacher kid. Hit a deep spot.

–Karen Tei Yamashita, author of Sense and Sensibility: Stories

Reading The Palm-Wine Drinkard by Nigerian novelist, Amos Tutuola, it’s like I’m listening back to my grandmother telling a story. Not only is the fantasy dragging me to strange places with wonderful creatures, but also the way the story is told is so familiar as if the storyteller is right in front of us. The repetitions of the sentence may feel strange at first, but over time it becomes like a bewitching drum rhythm.”

–Eka Kurniawan, author of Kitchen Curse: Stories, translated by Annie Tucker and others.

Camille de Toledo’s Thésée, sa vie nouvelle (editions Verdier) is a very intimate autobiography that nevertheless also tells the story of Europe through four generations with poignant force.

–Marie Darrieussecq, author of Being Here Is Everything: The Life of Paula Modersohn-Becker, translated by Penny Hueston

The Family Clause by Jonas Hassan Khemiri—one of the wisest portraits of a family across generations that I’ve ever read—funny, poignant, and just an absolute pleasure to read, with a brilliant translation by Alice Menzies.

–Dinaw Mengestu, author of All Our Names

This year I finished reading Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu, which has encouraged me to shift the focus of my writing, from describing the external world to examining my inner life. Proust was not simply chatting about his own life, but rather expressing the lives of all humanity through his own existence.

–A Yi, (translated by Jeremy Tiang), author of Two Lives: Tales of Life, Love and Crime from China, translated by Alex Woodend

Locked down, I read so many books this year, and loved quite a few, but here are my favorites, broken down by category. Favorite Novel: Blindness by José Saramago, recommended to me years ago, but it seemed too fantastical and dense: a pandemic where people suddenly go blind?! Come on. . . When the pandemic struck this year, I wanted books that could stand up to the strangeness and dark unreality of the times we found ourselves in. I could not put the novel down. Gripping, terrifying, a page turner but also deeply allegorical and morally transformative, Blindness earns its quiet and restless hope.

Favorite nonfiction book: Dictionary of the Undoing by John Freeman, again a book I needed to read NOW, and not just “because of” the pandemic. As we witnessed the heartbreaking divisiveness and violence of our country & world falling apart, this book gave me a vocabulary for reframing that world and moving forward. A lexicon for undoing broken structures of thinking and being that separate us, Dictionary provided new vocabularies of understanding, possibility, engagement. Each entry was like opening the small door of a word chosen for that letter of the alphabet and seeing new vistas, sweetness and light. As I told John in a fan letter, my go-to book for rekindling hope has always been Hope in the Dark by Rebecca Solnit. Dictionary of the Undoing is another companion text I’ll keep reading, rereading, recommending as we rebuild our Earth in the months, years to come. [Required reading by all public officials!]

Finally, favorite poetry book: (Oh man, hard to choose just one of Kate Daniels’s poetry books—I read through her whole opus this year.) If I have to pick just one of her collections, it’s A Walk In Victoria’s Secret—the poems have a narrative sweep, full-bodied, large-lined—reminiscent of Whitman. What I love about Kate Daniels’s poems is how they live inside the body, specifically a female body. The word made into unmistakable flesh. Moments, insights, phases, and stages I’ve never encountered in a poem and, in some instances, named for myself before. Her lyrical, oratorical, storytelling voice is like a current that carries me into and through feelings, moods, landscapes. Here is a poet, unafraid to see and say, proprieties be damned!

–Julia Alvarez, author of Afterlife and Already a Butterfly

One of the books I’ve had a great time reading during this pandemic year was Kurt Vonnegut’s Mother Night. Maybe because the novel’s narrator is telling us the story in solitary confinement in jail while waiting for his execution and, still, I find it a painful but heart-warmingly optimistic tale. It served, at least in my case, as a wonderful vaccine to self pity.

–Etgar Keret, author of Fly Already: Stories, translated by Sondra Silverston and others.

It was hot outside, but inside newly found quietude provided me room to explore what did and didn’t work for me as I tried to consider speculative futures beyond racial capitalism. Black Heretics, Black Prophets by Anthony Bogues, did work for me as it reminded me of an interior canon of thought beyond the flat, digitized iconography of this moment.

–Michael Salu is a writer, artist and creative director

As in all of her previous collections, Carolyn Forché’s long-awaited fifth book, In the Lateness of the World, takes Shakespeare’s question, “How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea, / Whose action is no stronger than a flower?” to its furthest ethical limit. The urgency she writes into is that beauty, broken, holds the possibility to not only renew or redeem our tragic world, but is necessary to make our world into a stronger whole. As such, Forché is our best proof, in this book, that poetry’s belatedness is action and poetry’s timelessness.

–Ishion Hutchinson, author of House of Lords and Commons

Intricately structured, epic in its ambition and achievement, Phil Klay’s Missionaries takes on America’s evilly systemic war-mongering, imperialist, racist, violence, with the moral and spiritual force of Melville and Dostoevsky. Missionaries is, in the largest sense, a truly great book.

–Lawrence Joseph, author of A Certain Clarity: Selected Poems

I’ve been reading slowly over the year Jean Genet’s last book, Prisoner of Love, or as the Arabic translation has it, Prisoner in Love. I tried to read the book more than twenty years ago when the translation by Kadhim Jihad first appeared, in 1997 with Dar Sharqiyyat. Trying to read it then immediately felt too alienating, as despair had its grip on our being with the political reality of Palestine, or in Palestine. This has only changed to the worst since, but now I got better at feeling despair without feeling defeated. Reading the book has contributed to that, as it embodies how literature can act as a manual for living against the bare life embodied in writing history. It is also a manual for how one can be next to one’s self, rather than be eternally captive by one’s self.

–Adania Shibli, author of Minor Detail, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette

Beneath its broad and terrifying investigation into corporate toxicity, Kerri Arsenault’s Mill Town undertakes to understand a deeper and more mysterious pathology—a sort of cultural Stockholm syndrome wherein a damaged population somehow learns to love its injury.

–David Searcy, author of The Tiny Bee That Hovers at the Center of the World, forthcoming in July 2021 (Random House)

I picked up the new translation of All My Cats, Czech writer Bohumil Hrabal’s 1986 memoir on a whim, thinking it would contain some delightful pensées on cats. What begins as a charming infatuation with a group of feral cats, descends into a squalid, brutal attempt to contain their numbers. The book evolves into a profound meditation on how we live with the enormous guilt, personal and inherited, that infects our daily lives and actions. Truly one of the most remarkable reading experiences I have ever had.

–Heather O’Neill, author of The Lonely Hearts Hotel

The most wildly entertaining and inventive novel I read this year was Enter the Aardvark, by Jessica Anthony. SAT question: Which of the following does not belong? A closeted contemporary Republican congressman, an eminent 19th-century British taxidermist, an African country of the sort that Donald Trump would classify as “shithole,” a stuffed aardvark with strangely human eyes. Okay, it was a trick question. They all belong. And so will you, reader.

–Richard Russo, author of Chances Are…

This fall, as megafires made the air unbreathable across the West, I found myself reading J.B. MacKinnon’s The Once and Future World, which transports the reader back to the planet before mankind reduced its abundance by 90 percent—to a Pennsylvania roamed by menacing black bulls, to a North Atlantic where ships were stalled mid-ocean by cod—to make a powerful case for “rewilding” the earth and ourselves.

–Amanda Rea’s work has appeared in Harper’s, Best American Mystery Stories and Freeman’s

Mitsuyo Kakuta is the kind of writer whose novels—about a woman who kidnaps the child of the man she’s having an affair with, or a bank teller who embezzles money to support her young lover, or an Edo-era prostitute who risks her life for the man she loves—no matter how far removed these are from the reality of our own lives, upon reading them we say, “These are our stories.” Her literary talents are laid bare before our very eyes. And so it is with Kakuta’s translation into modern Japanese of Murasaki Shikibu’s 11th-century classic, The Tale of Genji, that readers are saying, “This is our Genji.” Whether or not we were born in the Heian era or are familiar with court life of the period—or even if we are Japanese—it makes no difference. As long as you’ve got a human body and a human heart, you will definitely recognize the voices and sensations articulated in this version.

–Kanako Nishi (translated by Alison Markin Powell), author of Regarding Sam, Meeting Monkeys

Just when my brain felt the most mushy, re-reading How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe by Charles Yu, molded it back into shape so I could use it again. I used it to let the father-son relationship in the book reverberate through me, and it left me with a bright aching closeness to my own father.

–Xuan Juliana Wang, author of Home Remedies: Stories

This year I had to resist the temptation to spend all my time re-reading Philip K Dick over and over again and especially Ubik in which reality disintegrates unless it is vigorously sprayed with existential antiseptic. I enjoyed (if that is the right word…) revisiting John Christopher’s The Death of Grass —an eerie post-apocalyptic novel about, well, the death of grass and the global turmoil that ensues. I greatly admired the coruscating brilliance of Anakana Schofield’s Bina and Lina Wolff’s Many People Die Like You as well as the dreamlike wilds of Gary Budden’s London Incognita and Agustín Fernández Mallo’s The Things We’ve Seen. It was also a delight to read Enrique Vila-Matas’s latest, Mac’s Problem, about a novelist who abandons fiction and decides that, henceforth, he will stick to the sage and sensible facts. But then the facts become non-factual, reality resembles fantasy and what is our plaintive novelist to do!? Back to Philip K Dick once again—”it’s is sometimes an appropriate response to reality to go insane.”

–Joanna Kavenna, author of Zed

I read Marcial Gala’s The Black Cathedral (translated by Anna Kushner) all the way back in January or February—or approximately a century ago in emotional time—and still Arturo Stuart’s quixotic quest to build a massive cathedral in the Cuban city of Cienfuegos is vivid in memory. The arrival of Arturo and his family gives way to acts of violence, gallows humor galore, ghosts, surreal twists of fate, and a cast of unforgettable—terrifying, tender, charismatic—characters. The Black Cathedral is one of the best, most distinctive and memorable, books I read all year.

–Laura van den Berg, author of I Hold a Wolf by the Ears: Stories

La linea del colore is Igiaba Scego’s latest book, and she does not disappoint. This historical novel moves between the life of an African American painter, Lafanu Brown in 19th-century Rome, and a Somali-Italian curator Leila, in contemporary Rome. This riveting novel is an unflinching, haunting gaze on colonialism and bigotry. It is also a moving affirmation of the strength of sisterhood, one that can traverse time and space.

–Maaza Mengiste, author of The Shadow King

Something about this long year of lockdowns has favored the nature of reading that is just right for re-visiting Proust’s À la recherche du temp perdu. Proust’s multi-volume meditation on unrequited love, fashion, death, society and art has been a godsend.

–Ben Okri, author of Prayer for the Living forthcoming February 2021 (Akashic Books)

Alison Lurie has recently joined the company of the great comic immortals. I was chortling over a smart reissue of Foreign Affairs (first read decades ago) when I heard the news. Wittily astute, astringently congenial, her bold and playful novels will endure.

–Helen Simpson, author of Cockfosters: Stories

Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race, by Reni Eddo-Lodge, is a frank and incisive analysis of institutional racism, as told from the point of view of a young Black British woman. Compelling reading, it’s a call to action and reflection that may lead us into uncomfortable recognitions about ourselves.

–Xiaolu Guo, author of A Lover’s Discourse

One book that really floored me this year was Magnetized: Conversations with a Serial Killer by Carlos Busqued (translated by Samuel Rutter). This was an incredibly surprising, fascinating and dark but also deeply honest and human look into the world and mind of a man who has been in prison for over thirty years for a completely random murder spree he committed in Buenos Aires in 1982. With even less time to read than usual, and a shortened attention span, this year I also read a lot of 8th-century Chinese poetry—fitting given major themes of political turbulence, isolation and hermitude—in particular, Red Pine’s translations of Wei-ying Wu (In Such Hard Times) and Liu Tsung-yuan (Written in Exile).

–Chris Russell is a visual artist whose work has been published in The Believer, Virginia Quarterly Review, and Poetry Ireland Review.

Elena Skrjabina’s Siege and Survival paints a picture of civilian life during a conflict that has been studied over and over from a military perspective. The stark descriptions of hunger and the struggle to survive are so startling that they can read like surrealism while being firmly grounded in historical truth. Any city dweller can relate to Skrjabina’s portrait of Leningrad as a living thing, made up of buildings, boundaries and people.

–Patrick Hilsman is a New York-based journalist and analyst with experience covering the MENA region with a focus on the Syrian conflict, international weapons traffic, and refugee rights.

It’s a simple premise set within a tight frame—or is it? A mother goes out for the evening, leaving her young son at home, who in turn goes out for some fun of his own and then, once that’s done, to find her. But this is northern Norway in wintertime. Something bright and hungry burns inside each character and is present on every page, along with the winter cold and its brutal indifference. A careless reader might refer to this novel as “quiet,” but Hanne Ørstavik’s Love is animated by a propulsive current of terror. It’s a book that finds a home beneath your skin. Meanwhile, This Does Not Belong To You, published in 2018 alongside Hemon’s more traditional memoir, My Parents, is an incandescent accumulation of vignettes and stories from his childhood in Bosnia. Memory is Hemon’s main subject here—its mutability, its strange curves, how mysterious it is that some experiences fade into oblivion while others become a part of us, like a limb. This book, at once lyric and lucid, feels determined to resurrect what’s been lost to displacement and the passage of time, while simultaneously fully aware of the impossibility of return. “A lifelong project, it’s been for me,” Hemon writes, “going home.”

–Lauren Markham, author of The Far Away Brothers: Two Young Immigrants and the Making of an American Life

Two supreme essay collections have been a mainstay this year. Of Color is by poet Jaswinder Bolina, who proves himself such an intelligent guide to questions of integration in a book that is both philosophical and full of feeling. I also loved Brian Dillon’s Suppose a Sentence, where lines from Donne, Didion, Ruskin and more are poured over: it’s a joyous collection and I kept marveling at the ease with which Dillon performs the difficult act of reading well.

–Sunjeev Sahota, author of China Room, forthcoming July 2021 (Viking)

This year has been jam packed with brilliant reads but a few have really stayed with me, one of them being Inferno: A Memoir of Motherhood and Madness by Catherine Cho. Entirely uncompromising and beautifully written, Inferno moves through time from the psychiatric hospital where Cho is admitted after developing postpartum psychosis to her childhood and early relationships. There is something really lingering and honest about the way Cho lets the reader in on an enormously hard period in her life and I have been recommending this book to everyone I know.

–Daisy Johnson, author of Everything Under and Sisters

Like a true Met fan most of the time I’m either losing or playing catchup, and this year I caught up with Babitz’ Slow Days, Fast Company and Darius James’ uproarious and unputdownable Negrophobia and—holy shit—read those. I finally got around to Steve Toltz’s super hilarious, madcap novel A Fraction of the Whole which both razzled and dazzled me, and another at-least-half-a-maniac Australian writer, too, Lexi Freiman’s Inappropriation. As for stuff published in the hellscape of 2020–man I feel terrible for anyone who had a book come out in this dickhead of a year—I loved Marie Helene Bertino’s Parakeet, Justin Taylor’s Riding With the Ghost (I’m a sucker for the Dad stuff), and I’m halfway through Sarah Shun-Lien Bynum’s collection Likes which is impressing the hell out of me with its meticulous sentences and generosity of spirit and intelligence which feels very foreign to me right now because my brain is mush and I really need to drink some water but, you know, Bynum rules!

–Matt Sumell, author of Making Nice

The book I kept reaching for earlier in the year was Bitter Grass, an early collection by Gëzim Hajdari, newly translated by Ian Seed for Shearsman Books. The book-length poem begins: “No one knows if I still hold out/ in this corner of the burnt earth”; as the news became increasingly terrifying, and we lurched into the unknown, I kept repeating those lines to myself. I’m still holding out, and I hope that you are too”

–Andrew McMillan, author of physical and playtime

Style by Dolores Dorantes (2016). Every element of this distinctive work—its form, length, and ordering—contributes to the collective project of an intensely political text, demanding a reckoning with structures of violence in Mexico, and everywhere, from inside the rebellious consciousness of the women whose bodies are on the line.

–Nimmi Gowrinathan, author of Radicalizing Her: Why Women Choose Violence, forthcoming April 2021 (Beacon Press)

I am reading Barbara Jane Reyes’s Letters to a Young Brown Girl, an epistolary sequence of poems pushing back at the forces that oppress and erase Filipino women, from internal colonialization to white privilege. The poems are not only instructions in self-care, they are abundant, musical and downright badass.

–DA Powell, author of Atlas T

Zadie Smith’s astute and eloquent essays are always essential reading—but after this year’s harrowing spring in New York City her newest collection Intimations, written in the early days of the pandemic, felt especially necessary. It’s a gift to be accompanied by her clarifying gaze and nimble mind, and to overhear her thinking on topics ranging from writing to lockdown to inequality in this exceptionally intimate and vulnerable book. All royalties have been donated to charity.

–Deborah Landau, author of Soft Targets

Letters from a Stoic, by Seneca. “You ask me to say what you should consider it particularly important to avoid. My answer is this: a mass crowd.” Words to read as a health warning and solace for lost rationality; a refute of popularism.

–Rawi Hage, author of Beirut Hellfire Society

Yū Miri, Tokyo Ueno Station; cover design by Lauren Peters-Collaer (Riverhead, June)

Yū Miri, Tokyo Ueno Station; cover design by Lauren Peters-Collaer (Riverhead, June)

It‘s hard for me to choose between Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald and Tokyo Ueno Station by Yu Miri. In the former, Macdonald’s delicate and wise observations on humans, nature, humans within nature, freedom, and love spoke to me on a deeper level than many other books I’ve read this year. In the latter, Yu Miri weaves a quietly beautiful yet profoundly devastating tale that hasn’t left me since.

–An Yu, author of Braised Pork

I’ve actually read fewer books than usual this year, but came across several wonderful ones. The most impactful reading for me was maybe J.M. Coetzee’s The Death of Jesus, the final novel in his strange and powerful trilogy. It’s such a phenomenal achievement in fiction. It’s hard to grasp what the novels are exactly about, it feels like an allegory full of canonical and philosophical references where meaning hovers right before our eyes but remains out of reach. Nonetheless the narrative is consistently moving and profound, and incredibly self-sufficient. It creates its own rules and contains everything it needs. To me the journey of the boy David and those around him came across as a fable about our inspiring but ultimately doomed search for meaning. It states the importance of caring for each other, of committing to care, even when social struggle and the worst tendencies of the human spirit get in the way. And in the end literature itself proves to be the strongest tool for meaning and maybe transcendence. I’m eager to read the whole thing again. I’ve also enjoyed reading Franco Berardi’s essays and diaries published in Brazil by Ubu, full of inspired notes on the multiple crises of our times; Weather by Jenny Offill; Os supridores by José Falero and Marrom e Amarelo by Paulo Scott, both recently published in Brazil; and a lot of Tolstoy, always the purest reading pleasure.

–Daniel Galera, author of Twenty After Midnight, translated by Julia Sanches

Olga Tokarczuk, Bizarre Stories (translated beautifully into the Norwegian by Julia Wiedlocha), is one of the most breath-taking books I’ve read, so deeply original in its thinking and bizarre imagery, and yet so deeply embedded in modern society: a generous and powerful demonstration of what literature can actually be.

–Gunnhild Øyehaug, author of Knots and Wait, Blink, translated by Kari Dickson

No one was better company this year than Lucille Clifton, whose incandescent poems shone a path through the many dark days that enveloped us. I returned to How to Carry Water: Selected Poems of Lucille Clifton so often that a handful of her poems took up residence in my memory and kept coaxing my imagination to better places. These poems—capsule joys, wisdom nested in wit, with her capacious voice as attuned to the simple beauties as the everyday horrors—has a pull so strong that I was frequently tempted to stand on empty street corners and fill the spaces with Clifton’s resonant words.

–Garnette Cadogan is an essayist and a Visiting Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture at the University of Virginia

I absolutely loved So I Looked Down to Camelot, a book of short and vertiginously strange poems by the late British poet Rosamund Stanhope. Originally published in 1962, Flood Editions reissued the book in January, when I first encountered and devoured it. The poem titles alone are worth the price of admission—“The Boy With the Next-Door Face;” “The Light Puts Out the Conifer”—and Stanhope’s penchant for off-kilter rhyme and surprising personification lend a timeless, fabular quality to lines like, “Warm granaries / Hoard their Julys / By that synthetic sun, the grate.” If that’s not endorsement enough, the book is also often uproariously funny. Read it whenever you need “the drink of a dream.”

–Maggie Millner is a poet whose work has appeared in Freeman’s, Poetry and The New Yorker

I was stirred by No Presents Please by Jayant Kaikini, a surreal collection of stories about various denizens of Mumbai, all of them outsiders in some way, and their off-kilter attempts to make their way in the unforgiving city. Tejaswini Niranjana’s translation from Kannada is sharp and bitingly funny.

–Jeremy Tiang, translator and author of State of Emergency

My favorite book this year was Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia. I thought it was highly imaginative, entertaining, and I read it in one sitting. Stayed up until 5 am to finish it.

–Reyna Grande, author of A Dream Called Home

I’ve been so distractible this year that I was surprised and grateful to find myself immersed in Yiyun Li’s Dear Friend, from My Life I Write to You in Your Life, wanting it never to end. This 2017 collection of essays on the writing life is about love, time, mentorship, recovery, and solitude. (Read Li’s gorgeous stories before and after.) I also found my way to francine j. harris’s Here is the Sweet Hand: Poems, a 2020 collection I admire for its pulse, solace, and the way it maps—in new syntactical fittings and aerial linguistic maneuvers—a mind wrestling with eros, intimacy, distance, the boundaries of the self, and race. (It’s also funny, bitter, melancholy, and tender.)

–Catherine Barnett, Human Hours: Poems

I loved All Our Yesterdays by Natalia Ginzburg. It moves relentlessly through some of the darkest years in Italian history, yet remains leavened by the serene detachment of Ginzburg’s voice and the generosity of her vision. It’s utterly brilliant.

–Anthony Marra, author of The Tsar of Love and Techno

From his 2019 Page-Barbour Lectures at his alma mater, the University of Virginia, Daniel Mendelsohn has produced an exquisite and thrilling work of scholarly peregrination. As he discusses the technique of ring composition, Mendelsohn goes on to create a beguiling narrative that employs it, folding the works of W.G. Sebald, Erich Auerbach, Francois Fenelon, and Homer into his own experiences of trying to write. In this time of physical confinement and mental burden, Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative, and Fate springs a lock, allowing us to roam magisterially through centuries and geographies. It is an exalting read.

–Oscar Villalon, managing editor of Zyzzyva

I read Nina Renata Aaron’s beautifully written, sordid memoir about codependence, Good Morning Destroyer of Men’s Souls and couldn’t put it down. A welcome intervention against stories of addiction focusing on the addict, Aaron shows us the fallout of being in an addict’s thrall.

–Emily Raboteau, author of Searching for Zion: The Quest for Home in the African Diaspora

In late February 2020 I read White Noise, Don DeLillo’s 1985 novel about an “airborne toxic event,” one month before global recognition of our current airborne toxic event, and seven months before I published a book about airborne toxic events, all of which plonked an exclamation point on the bewildering joy I had experienced in reading DeLillo’s exuberant prose for the very first time. A maelstrom of human terror and hilarity, White Noise is a feisty, prophetic, tender satire and screed, glorious in its ramparts of high intensity and its guttered sadness, about unbridled consumerism, conspiracy theories, academic absurdities, and a subulate examination of slow but violent ecological collapse. “Every day on the news there’s another toxic spill. Cancerous solvents from storage tanks, arsenic from smokestacks, radioactive water from power plants. How serious can it be if it happens all the time?” a character wonders about the toxic cloud.

While many of us believe the flip of a calendar will somehow correct course and end the banal repetition of monstrous policy and behavior we’ve become accustomed to, DeLillo’s question still hovers on my lips as we fold into 2021: is it possible for our leaders to emerge from such white noise (largely of their own making) and arrest the environmental, cultural, and sociological cataclysms before us? Or have we reduced expectations of our own capacity so much that like DeLillo’s characters at the end of the book, stand mesmerized in front of a supermarket, caught between the past and the future, between the real and unreal?

–Kerri Arsenault, author of Mill Town

I’m almost done with Christie Tate’s Group, and I’m loving it! Sometimes you need a story that reminds you that you’re not alone and that things just might turn out okay, you know? Tate’s writing alternates from heartbreaking to hilarious and is full of such clarity and insight about what it means to truly be vulnerable with yourself and with others. Makes me want to hand this book to my 24-year-old self and say, here, read this. It’ll help.

–Nicole Im’s work has appeared in Freeman’s, Literary Hub, Hinterland Magazine and Pigeon Pages

I’m in awe of how language speaks against power, against loss in Michael Prior’s Burning Province, a collection about the internment of Japanese-Canadians at the outbreak of World War II. It’s a journey between houses with faces broken by eviction notices; a journey of tenderness, testimony, and fearlessness.

–Valzhyna Mort, author of Music for the Dead and Resurrected: Poems

The Cost of Living: A Working Autobiography by Deborah Levy has over 100 pages, but during the past year I spent most of my reading time revisiting these elegantly written memoirs. I haven’t finished reading it because I will still be coming back to certain passages in the future. The most important books are those we keep coming back to.

–Semezdin Mehmedinović, author of My Heart: A Novel, translated by Celia Hawkesworth, forthcoming in March 2021 (Catapult)

__________________________________________

The preceding is from the Freeman’s channel at Literary Hub, which features excerpts from the print editions of Freeman’s, along with supplementary writing from contributors past, present and future. The latest issue of Freeman’s, a special edition gathered around the theme of love, featuring work by Louise Erdrich, Haruki Murakami, Maaze Mengiste, Mieko Kawakami, Olga Tokarczuk and Semezdin Mehmedinovic, among others, is available now.