What Chickens Know: On Bonding with Birds and the Language of Hens

Sy Montgomery Explores the Complex World of Breeding and Studying the Famous Fowl

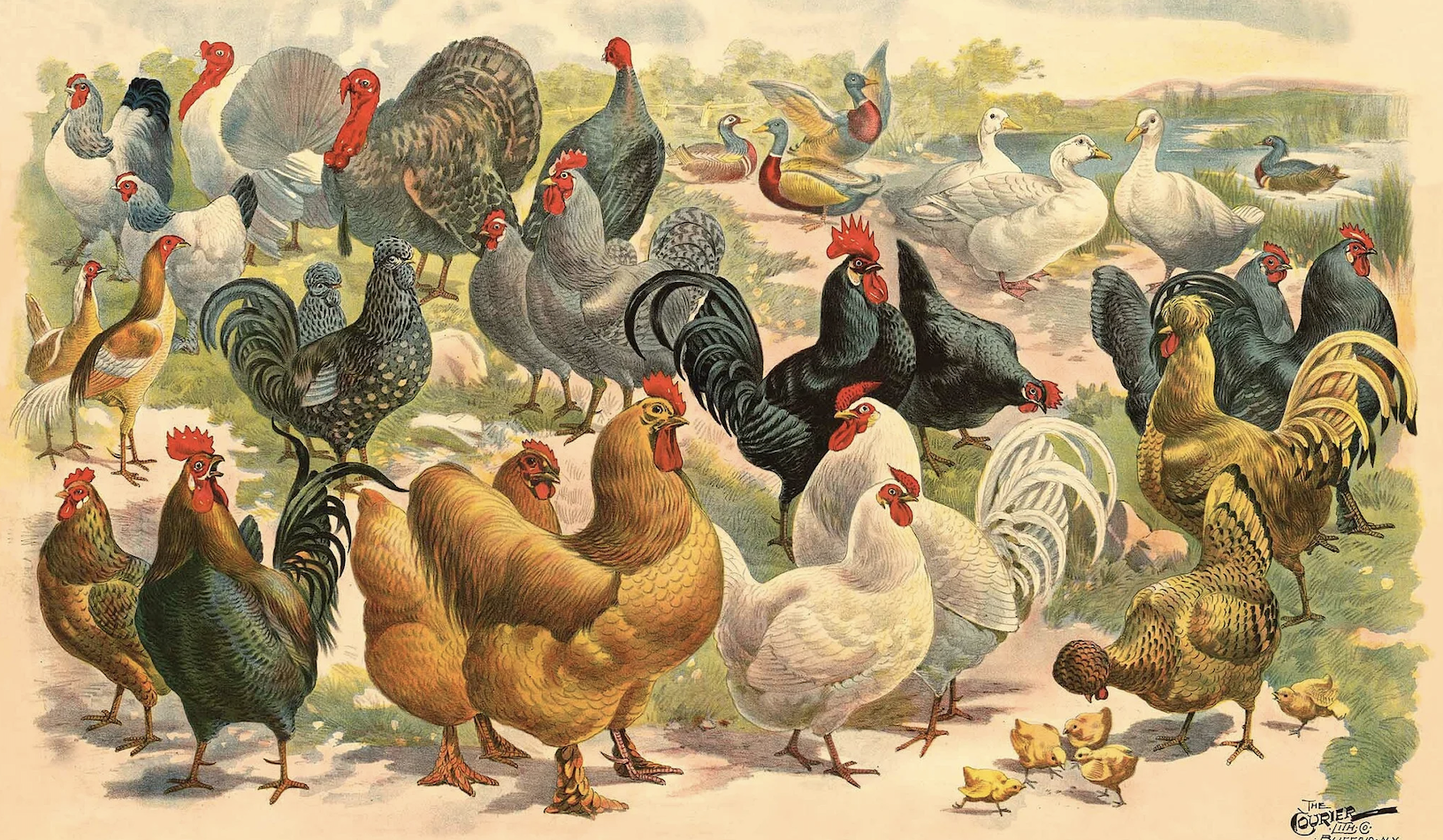

Chickens with poufy topknots; chickens with feathered feet; chickens with turquoise earlobes; chickens who lay green eggs (though not with ham); chickens with tails that can grow twenty feet long….When I placed my initial order with the hatchery, I had many breeds to choose from.

Chickens have been living with people for a very long time (by some reckoning, as long as eight thousand years—longer than donkeys and horses, longer than camels or ducks, and by some accounts, even longer than pigs and cattle).

Starting with the red jungle fowl of Southeast Asia (who looks pretty much like the rooster on the Kellogg’s Corn Flakes box), through selective breeding people have created as many as three hundred and fifty different varieties of chickens—chickens spangled with iridescent feathers, chickens with naked necks (these are called turkens but are really chickens, not crosses with turkeys), chickens standing tall on long legs like basketball players, miniature chickens called bantams who might weigh only a pound.

Every winter we muse over the catalogs of the chicken hatcheries the way gardeners dream over seed catalogs. We glance at the bargains: one catalog carries a Top Hat Special, an assortment of crested breeds from the five-toed Mottled Houdans to the golden Buff Laced Polish, all of whom look like they are wearing giant, curly wigs made out of feathers. Even the babies sport little top hats.

There’s usually a special on Feather Footed Fancies: all these varieties have feathered feet, making the birds look a bit like they are wearing floppy slippers. There is even a Fly Tyer’s Special, a selection of chickens whose feathers can be used to fashion particularly attractive fishing lures.

Chickens have been living with people for a very long time (by some reckoning, as long as eight thousand years—longer than donkeys and horses, longer than camels or ducks, and by some accounts, even longer than pigs and cattle).

Of course, we ignore the Frying Pan and Barbecue specials; I’m a vegetarian and certainly wouldn’t eat anybody I know.

What we’re really looking for are handsome, vigorous chickens who do well in cold climes. With their glossy black feathers, red, upright combs, and ample bodies, our Black Sex-Links were all these things. We sometimes called them “the Nuns,” especially when they raced out of their coop each morning like a flock of chatty Sisters leaving a convent in their billowy black habits.

Such a uniform appearance did they present that, without noting the subtle differences in the shape of their combs, it was nearly impossible to tell them apart. (Scientists faced with this problem sometimes outfit the hens with numbered armbands affixed to a wing.) Adding birds of different breeds presaged an important change in our understanding: now that it was easier to tell birds apart, the distinct personalities of individuals began to reveal themselves more clearly.

Kate and Jane next door took this opportunity to give the chickens names. I had not done so before because of a military adage learned from my father, an army general, which warned, “Never name the chickens.” I knew this wasn’t about poultry, but about the commander’s responsibility to remain objective about the troops he must choose to send into battle.

But somehow it always stuck with me that something bad would happen if you named your hens. In fact, the only one of the Nuns who’d been named before the arrival of the new babies bore the badge of near catastrophe: the girls named her Foxy Lady after an encounter with a fox left her with no tail feathers.

But with the coming of age of our creamy buff Speckled Sussexes and our black-and-white Lakenvelders came more names: Snow White for one of the “Lakes,” who was exceptionally beautiful and loved to fly; Madonna for a loud and theatrical Speckled Sussex; Matilda for one of the remaining Black Sex-Links, who, now older, walked with a rolling gait resembling a waltz….

Soon it became evident that some hens were consistently outgoing and others shy; some were loud and others quiet; some cautious and others reckless. This was particularly obvious whenever the hens faced a threat, such as a hawk flying overhead. Some hens hid in pricker bushes; others raced inside the coop. Some dashed behind a large board that leaned against an outside wall of the barn. Some individuals would continue to hide for more than an hour.

They were so good at hiding that sometimes, alerted by their alarm calls, I’d rush outside to try to defend them and spend half an hour trying to find them and entice them from their hiding places. Brassy Madonna was often first to emerge, while Foxy Lady, surely remembering the horrible fox, stayed immobile the longest. But all of them under- stood that even though the hawk might not be visible, it still might be lurking somewhere nearby.

Chickens both remember the past and anticipate the future. This has been clearly demonstrated in the laboratory. In one study, published in the journal Animal Behaviour, Silsoe Research Institute biologist Siobhan Abeyesinghe and her co-authors tested hens with colored buttons. When hens pecked at a particular button they were rewarded with food.

The word “augury” comes from the Greek word meaning “bird talk,” for to understand the language of birds was to understand the gods.

But they got an even bigger reward if they learned to postpone their pecking. If they waited—for up to twenty- two seconds—they got even more to eat. The birds chose to wait for the jackpot more than 90 percent of the time.

Experiments like this show that chickens “can do things that people didn’t think they could do,” says Christine Nicol, professor of animal welfare at the University of Bristol in England. “There are hidden depths to chickens, definitely.”

In our attempt to plumb those depths, the girls and I tried to decipher the chickens’ language. At first my husband dismissed our efforts, insisting that most of what they were saying was, “I’m a chicken. You’re a chicken. I’m a chicken.”

He gave them more credit than most scientists did for many years. Even though birds have the greatest sound-producing capabilities of any vertebrate—far superior in both volume and range to the greatest human opera star—their distinctive calls and elaborate songs were not considered true communication.

Even parrots who spoke sensible phrases in English to their human owners were dismissed as mere mimics. Birds’ spectacular voices were merely unconscious, uncontrolled noises reflecting the birds’ inner states (which were also assumed to be unconscious).

The ancients knew better. The word “augury” comes from the Greek word meaning “bird talk,” for to understand the language of birds was to understand the gods.

And the Cabot girls and I knew better, too. We could feel the anguish in the Ladies’ calls when they spotted a predator; we could read their delight when someone found a mother lode of worms or beetles in the compost pile.

We discovered, too, that some hens announce the blessed moment when they have laid an egg: a loud, measured series of rising buk-buk-buk-AHH! sounds. We suspected this meant more than just “Ouch!” Hens may perceive their eggs as gifts that may be presented to their rooster, their flock-mates, or an honorary chicken/person.

On Farm Life Fo- rum’s Web page for poultry keepers, a woman wrote of a chicken her father had kept as a pet when he was a boy. Each evening, the hen appeared at the door of the house and would peck to be let inside. When the door opened, she would proceed directly to the boy’s bed—where she would lay an egg on the pillow.

Then, gift delivered, she would stride back to the door and return to the henhouse.

______________________________

Excerpted from What the Chicken Knows: A New Appreciation of the World’s Most Familiar Bird by Sy Montgomery. Copyright 2024 © by Sy Montgomery. Reprinted by permission of Atria Books, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC.

Sy Montgomery

Sy Montgomery is a naturalist, adventurer, and author of more than thirty acclaimed books of nonfiction for adults and children, including The Hummingbirds’ Gift, the National Book Award finalist The Soul of an Octopus, and the memoir The Good Good Pig, which was a New York Times bestseller, as well as What the Chicken Knows: A New Appreciation of the World's Most Familiar Bird. The recipient of numerous honors, including lifetime achievement awards from the Humane Society and the New England Booksellers Association, she lives in New Hampshire with her husband, writer Howard Mansfield, and a border collie.