What Can We Salvage of Objectivity?

From the Introduction to Michiko Kakutani's The Death of Truth

For decades now, objectivity—or even the idea that people can aspire toward ascertaining the best available truth—has been falling out of favor. Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s well-known observation—“Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts”—is more timely than ever: polarization has grown so extreme that voters in Red State America and Blue State America have a hard time even agreeing on the same facts. This has been going on since a solar system of right-wing news sites orbiting around Fox News and Breitbart News consolidated its gravitational hold over the Republican base, and it’s been exponentially accelerated by social media, which connects users with like-minded members and supplies them with customized news feeds that reinforce their preconceptions, allowing them to live in ever narrower, windowless silos.

For that matter, relativism has been ascendant since the culture wars began in the 1960s. Back then, it was embraced by the New Left, eager to expose the biases of Western, bourgeois, male-dominated thinking; and by academics promoting the gospel of post-modernism, which argued that there are no universal truths, only smaller personal truths—perceptions shaped by the cultural and social forces of one’s day. Since then, relativistic arguments have been hijacked by the populist Right, including creationists and climate change deniers who insist that their views be taught alongside “science-based” theories.

Relativism, of course, synced perfectly with the narcissism and subjectivity that had been on the rise, from Tom Wolfe’s “Me Decade,” on through the selfie age of self-esteem. No surprise then that the Rashomon effect—the point of view that everything depends on your point of view—has permeated our culture, from popular novels like Fates and Furies, to the television series The Affair, which hinge upon the idea of competing realities or unreliable narrators.

I’ve been reading and writing about many of these issues for nearly four decades, going back to the rise of deconstruction and battles over the literary canon on college campuses; debates over the fictionalized retelling of history in movies like Oliver Stone’s JFK and Kathryn Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty; efforts made by both the Clinton and Bush administrations to avoid transparency and define reality on their own terms; Donald Trump’s war on language and efforts to normalize the abnormal; and the consequences that technology has had on how we process and share information. In The Death of Truth, I hope to draw upon my readings of books and current events to connect some of the dots about the assault on truth and situate them in context with broader social and political dynamics that have been percolating through our culture for years. I also hope to highlight some of the prescient books and writings from the past that shed light on our current predicament.

Truth is a cornerstone of our democracy. As the former acting attorney general Sally Yates has observed, truth is one of the things that separates us from an autocracy: “We can debate policies and issues, and we should. But those debates must be based on common facts rather than raw appeals to emotion and fear through polarizing rhetoric and fabrications.

“Not only is there such a thing as objective truth, failing to tell the truth matters. We can’t control whether our public servants lie to us. But we can control whether we hold them accountable for those lies or whether, in either a state of exhaustion or to protect our own political objectives, we look the other way and normalize an indifference to truth.”

![]()

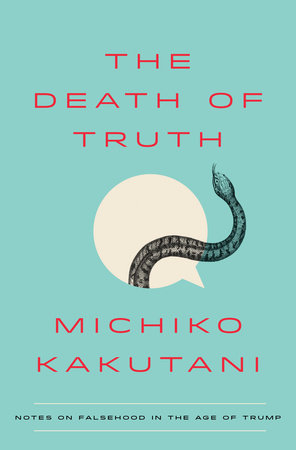

From The Death of Truth, by Michiko Kakutani, courtesy Tim Duggan Books. Copyright 2018.

Michiko Kakutani

Michiko Kakutani, the former chief book critic of The New York Times, is the author of the 2018 bestseller The Death of Truth: Notes on Falsehood in the Age of Trump.