What Can the Artist Do in Dark Times?

Paul Scraton on the Life and Legacy of Käthe Kollwitz

On a Sunday morning in January, on my way to visit the grave of the artist Käthe Kollwitz, I passed through the people who had gathered at the Memorial to the Socialists in the Friedrichsfelde cemetery in eastern Berlin. They came, as they did every year, to leave red carnations on the graves of Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, as well as other members of the German socialist movement who were buried there. Red flags fluttered against a clear, winter sky. Brass bands played left-wing anthems. Supporters of different parties, movements and factions handed out newspapers or clamored for signatures. At the edge of the crowd, police stood in small groups, helmets off, observing the scene.

From where the people gathered by the cemetery entrance and at the Memorial itself, it was a short walk to Kollwitz’s grave, and although the sound of the brass band drifted along the tree-lined path with me, the scene was soon calm. Standing by the Kollwitz grave, where someone had broken away from the crowd before me to leave a single red carnation against the headstone, I had the corner of the cemetery pretty much to myself.

The centerpiece to the Memorial to the Socialists tells us that Die Toten mahnen uns. The dead remind us. Käthe Kollwitz’s grave makes no such statement. But as I placed a small rock on the headstone, I couldn’t help think that perhaps it should. Käthe Kollwitz died almost 75 years ago, just a few weeks before the end of the Second World War. All those decades on, her work continues to speak to us, to remind us of the stories of the past and those she bore witness to. In her etchings, prints and sculptures, Kollwitz continues to remind us of what it means to be an artist and the possibilities of art in the most troubling of times. It was why, on that clear, cold Sunday morning, I was there.

*

Käthe Kollwitz was born in the Baltic port city of Königsberg (today: Kaliningrad) in 1867, studied art in Berlin and Munich, before settling in the German capital in 1891. Her husband was a doctor, and together they moved to the working class neighborhood of Prenzlauer Berg. There, in a Berlin that was the powerhouse of the German Industrial Revolution, Kollwitz witnessed the realities of life for those who worked in its factories and lived in its tenement blocks. What she saw on the streets and in the lives of those who passed through her husband’s surgery, who provide inspiration for her work. There was pain and trauma in what she observed, but there was also beauty, Kollwitz would later write. Her attempts to reflect that beauty in the art cycles that linked the Berlin of the late 19th century with historical events would make her name.

Two of her most famous works from her first couple of decades in the city were the etchings included in the cycles A Weavers’ Revolt (1894-1897) and Peasants War (1901-1908). In these she combined the imagery inspired by what she saw all around her with stories of the past, namely the Silesian Weavers’ Revolt of 1844 and the German Peasants War if 1523-1526. This was art that gave voice to those who had suffered and reflected the lives of those who suffered still, created with compassion and respect, explicitly linking history with Kollwitz’s present.

If there is a shift in Kollwitz’s art it came with the rupture of the First World War. Not only did the grand scale of the tragedy, the millions of lives lost and violently altered on the battlefields of Europe, move Kollwitz towards works that were explicitly pacifist, but now the suffering was also personal. Both her sons volunteered to fight. Hans would make it back. Peter would not. He died in the early months of the war on a Belgian field and would stay there, buried in a war cemetery with tens of thousands of his fallen comrades.

*

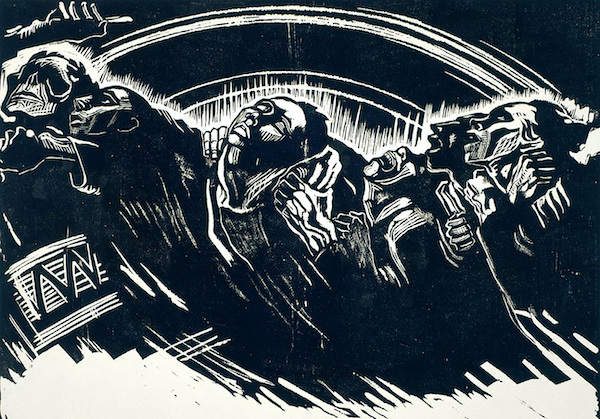

To poverty and hunger, add war. As Berlin entered the so-called Roaring Twenties, Kollwitz began work on a cycle of seven woodcuts that would take her the best part of two years. The titles of the War cycle—to my mind one of her most powerful and affecting works—tell something of the story. The Sacrifice. The Volunteers. The Parents. The Widow I. The Widow II. The Mothers. The People.

This was the art of war that depicted not the battlefield, nor acts of heroism. Most of those depicted in the cycle are what we would call “non-combatants.” In particular, they are mothers. At the Käthe-Kollwitz-Museum in the west of Berlin I stood in front of the War cycle, profoundly moved. What was it, I asked myself, that gave these images such power, such resonance, almost a hundred years after they were created?

“As the Nazis swelled their ranks,” she wrote, “the majority of decent Germans carried on with their daily lives, neither oblivious nor sufficiently alarmed.”

Perhaps it was that Kollwitz understood, and through her art showed, that war means much more than what happens on the battlefield. That war is not simply two armies facing off, with the lives of poor souls like Peter Kollwitz being the cost. The impact of war was always felt by more than just the soldiers fighting, but in the century that has passed since Kollwitz painstakingly created her seven woodcuts, we can see and feel ourselves that it also means bombing raids and civilian casualties, it also means friendly-fire deaths and improvised explosive devices, and it also means extraordinary rendition and drones bringing death and destruction while being piloted from so many miles away.

What remains constant is the pain, the sense of suffering and of loss. The faces of those who populate Käthe Kollwitz’s war cycle—the volunteers, the widows, the mothers—could come from so many times and so many places. The Berlin of 1921 is the Sarajevo of 1994. It is the Aleppo of 2016 or the Baghdad of the early days of 2020.

*

A few days after my visit to Käthe Kollwitz’s grave, I went with the German artist Sebastian Neeb to the Kupferstichkabinett in the Kulturforum, not far from Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. In the study room we looked up some of Käthe Kollwitz’s sketches and prints, spreading them out to get a feel for both her working process and how subtle changes to the images as she worked increased their visual power. We talked about what it is that images have, whether photographs, paintings or film, to shock or move us, to get a point across. And we talked about Kollwitz’s technique and the skills required to create these works that speak to us across the decades.

The Volunteers, 1921.

The Volunteers, 1921.

Technique alone was not enough, Neeb said as we sat down for a coffee in the canteen afterwards. “Without the story to tell,” he continued, “and her feeling and emotion that is behind it… well, all the technique in the world wouldn’t matter.”

Look long enough at any work of art and it becomes imprinted behind your eyelids. Kollwitz’s subjects were traveling with me as I moved between the different places in Berlin that link the artist’s life and work. There was no question that her work spoke to me as it speaks to many others. That it haunted me as it no doubt haunts others. But could her art, could any art, really make a difference?

Kollwitz created the War cycle to explore the cost of war. She created posters for causes that she believed in, to help the fight against hunger, poverty and militarism. She used the name she had made with her art to back an open call for unity against the National Socialist threat. But in the end her art and her name was no match for the Nazis. Another war was soon to follow. Millions more dead, including Kollwitz’s grandson, called Peter like her son. War destroyed her home and forced her out of the city she’d lived in for more than 50 years. She would not live to see the end of it.

How important can art be really?

In the Kulturforum canteen, Neeb finished his coffee.

“It can help us shape our thoughts,” he said. “It can help us find and articulate our opinions. On an individual level. More than that…”

He paused for a second.

“We shouldn’t overestimate the power of art,” he said. “But we shouldn’t underestimate what it can do either.”

*

In den finsteren Zeiten,

wird da auch gesungen werden?

Da wird auch gesungen werden.

Von den finsteren Zeiten.

In the dark times

Will there also be singing?

Yes, there will also be singing,

Of the dark times.

–from the Svendborger Gedichte, by Bertolt Brecht

*

In her art, Käthe Kollwitz sang of the dark times. She never hid from them, from the pain and suffering of others or indeed herself. The British poet Ruth Padel has written persuasively on the power of visual art, including Käthe Kollwitz, and poetry to engage with trauma and create something that speaks to others. “No poem ever stopped a tank,” she wrote in The Guardian in 2018, “But by putting vivid words, memorably together, in ways that resonate more loudly the deeper you go, poetry can address huge issues very powerfully.”

Reading these words, I couldn’t help but think of Käthe Kollwitz’s War cycle, as well as her sculpture The Grieving Parents, which stands guard over the grave of her son Peter and his comrades at the Vladslo German war cemetery in Belgium. There are many other places they could be standing guard, reflecting loss and mourning, reminding us that when people die in the thousands or millions, each individual leaves behind survivors who hold tight to their memory as Kollwitz’s The Grieving Parents do, down on their knees. You do not need to be able to speak German to understand what Kollwitz was trying to say. This is both the power of her art but also the possibility of what art can do.

*

Returning home from the Kupferstichkabinett I contacted Anne Mager, a friend and the Ireland-based curator of a number of projects, including an exhibition The Other Side at the Dortmunder U, that reflect on contemporary Irish positions to focus on the personal, political and cultural impact of borders and social division. As a German curator whose projects and exhibitions have dealt with contemporary social and political themes, what did she think about the possibility and responsibility of art and the artist to deal, as Kollwitz did, with troubled times?

The faces of those who populate Käthe Kollwitz’s war cycle could come from the Berlin of 1921 is the Sarajevo of 1994. It is the Aleppo of 2016 or the Baghdad of the early days of 2020.

Mager began by making it clear that art has no obligation to be anything other than art. It had no responsibility other than to itself. Not to entertain or inform, nor to be political or education.

“That said,” she continued, “what it can do is give us the unique opportunity to see the world and its issues from a completely different perspective. It challenges our ways of seeing and thinking about the world around us. Artists can share their experiences while leaving enough space for the viewer to connect to it individually.”

When I look at Käthe Kollwitz’s work I think not only of the stories she is telling, of 19th-century weavers and living conditions in Prenzlauer Berg, the devastation of the First World War or the rising nationalist, militarist threat, but how it also speaks to the world today. It resonates in ways she could not possibly have imagined because of the shifts that have taken place in the 75 years since her death. But the genius lies in the space she left, to allow each one of us, across time and space, to connect with it in our own way, in relation to our own experiences. The possibility of art.

*

The artist is under no obligation to challenge the dangers in troubled times, but how about the citizen?

When Käthe Kollwitz signed the call for unity in the face of the National Socialist threat in 1932, alongside Heinrich Mann, Albert Einstein and others, she came face to face with not only the intransigence of the fractured left but also what Andrea Weiss, in her book In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain, described as an ambivalence in the general public. “As the Nazis swelled their ranks,” she wrote, “the majority of decent Germans carried on with their daily lives, neither oblivious nor sufficiently alarmed.”

Kollwitz was not alone in calling attention to the danger, both in her art and in her public actions. Her fellow artist Georg Grosz had warned of Hitler’s threat as early as 1923. The writer Joseph Roth used his newspaper articles to reflect on the dangers of the rising nationalist tide. But there were not enough willing to heed the warnings. The nonpolitical outnumbered the political. The apathetic were more than the engaged. And it was true in the art world as it was the wider society.

Much is made, as we enter this new decade, of the parallels between then and now. We look at the world around us and we imagine history repeating. The dangers we face are the dangers Kollwitz and the others warned us about. Let us not make the same mistake again. But nothing is ever exactly the same, so instead we need to reflect on what we can use for our own, very different situation.

In a series of essays for the book Known and Strange Things, Teju Cole reflected on actions taken by a government in the name of its people, from drone strikes as part of the global war on terror to abuses much closer to home. “No citizenry,” he wrote, in 2016, “can shirk the responsibility of calling the state’s abuse of power to account.” And yet, while not oblivious to the dangers of our contemporary world, from the state’s abuse of power, rising populist nationalism and militarism to poverty and the catastrophic impact of the climate crisis, we seem to be not sufficiently alarmed. I cannot help but think that Kollwitz would agree with Cole. We all have a responsibility to sound the alarm. And the possibility of art is that it can sound it in ways that only art can.

Paul Scraton

Paul Scraton is the editor-in-chief of Elsewhere: A Journal of Place and the author of Ghosts on the Shore: Travels along Germany's Baltic Coast (Influx Press). His debut novel Built on Sand was published by Influx in 2019. He lives in Berlin.