What Can Superhero Stories Do For Us In 2022?

Peter Kalu on the Origins Stories That Made Him Who He Is

Every Saturday I flew to the local picture houses. To the Scala. To the Trocadero, aka the Flea Pit. I sank into the fading majesty of those places—they were working-class Opera Houses in miniature—with rococo frontages, ornate stucco interior ceilings, plush red carpeting, sprung seats, and liveried ushers; even the men who tried to grope you if you sat on the back row wore black ties and clean white shirts.

It was in these grandiose, crumbing, faded Empire settings that I first met my celluloid Superheroes. I was seven years old. Inside these theaters, I was no longer the shy boy with the scabby knees, holed shoes, and tangled Afro. I was Superman, Spiderman, and Batman all rolled into one.

The start of that unforgettable Pearl and Dean soundtrack accompanied by its vertiginous time-warp tunnel meant our superheroes were in the wings, warming up; the projectors were being loaded, the safety curtain was about to fly. It was mid-summer. We were ready with radioactively glowing Kia-Ora orange juice, teeth-gluing popcorn, tiny tubs of ice-cream, and as many bags of sweet as we’d managed to sneak in. We sank into the seats and slurped, eyes glued to that silver screen. The show started, and we drank in the phrases dreamed up by scriptwriters in place of swear words: Holy Whiskers, Batman! Holy Long John Silver! Ker-Pow! Holy Understatement! Holy Ravioli!

Enrapt. Agog. Breathless. We left the picture house groggy on technicolor stimulation. That day, we tumbled out of the Scala to see a boy our age run into the road and get hit by a car. A man in the crowd burst forward and lifted the car up with his bare hands while a group of people dragged the boy out from under the wheels. He dusted himself off and hobbled away as the crowd, and the car-lifting superhero, dispersed. In that moment, I knew there were superhumans not only in the Scala but living among us. We just needed to know how to see them.

My juvenile cinema trips faded when Marvel Comics burst onto the scene. They were the high-gloss, color-saturated new comics on the block. They soaked up all your pocket money if you bought them new. I generally read hand-me-downs: The Incredible Hulk, Fantastic Four, Spider-Man, The X Men. My smug friends pitied me as the sad boy who was reading last week’s comic and so didn’t know if The Hulk crashed through that burning building and pulled out the Naïve Scientist who’d made a World Saving Discovery—or not. I was unforgivably late: in the way that light from the distant parts of our Milky Way Galaxy can take thousands of years to reach us on earth, so the comics I was reading were ancient stuff.

In the twenty-first century, we are wisely wary of superheroes. They can very often turncoat and transform into villains.

Comics during this time in my life were an escape from real-life family dramas. These ranged from my sister failing to return at night from her stints as a Bunny Girl at the Playboy Club, to my Import-Export-mad dad fretting over what to do with 50,000 pairs of European-sized ladies’ underwear that had proven useless to prospective buyers in Nigeria—owing to “the generosity of Nigerian women’s bottoms compared with those of the English” (his words, not mine)—and my brother’s near-fatal late-night asthma attacks.

I cast aside all this 3D melodrama for a 2D comic Spider-man flinging himself across Gotham’s skyscrapers in pursuit of the villainous pasty-faced jewel thief. I still went to the movies. But I became—with my film aficionado friend Sanjay Jobanputra—a Clint Eastwood fan: we bobbed along to any cinema where Clint was showing, loving his short-tongued way with words. “Do you feel lucky, punk?” was Dirty Harry. We admired too the Super-Vigilante Death Wish franchise’s Charles Bronson and his “Do you believe in Jesus? You’re gonna meet him.” These were my new superheroes. Until they weren’t.

By my late teens, I had developed a growing political awareness, fed by reading the Communist Manifesto (courtesy of People’s Publishing House, Beijing). I joined a revolutionary circus (I kid you not), fell in and tumbled around with anarchists, Trotskyites and plain orthodox communists. This environment fed a repulsion for the exceptionalism and individualism that superheroes represented.

I denounced my childhood film-watching and comic reading. I rejected the Eastwoods and Bronsons and McQueens. The Black Power texts grabbed me, and I joined the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party, spending time deep-diving into Capitalism and Slavery (Eric Williams), the Autobiography of Malcom X, How the West Underdeveloped Africa (Walter Rodney), Steve Biko’s I Write What I Like, and the like. Emerging from these works, I doubly rejected the West’s superheroes: the white man can never save the black man—on the contrary, the white man is the cause of all the black man’s problems, I decided. Or, to rephrase Audre Lorde, “the Master’s superheroes will never overthrow the master’s house.”

Side-stepping Western popular culture, I immersed myself in Yoruba mythology and began to adopt West African gods in my narratives. Cue my radio plays: Xango’s Challenge featured a living embodiment of the God of Lightning, Shango. AfroGoth, my award-winning radio play for Radio 4, starred Ogun, God of War, in a supernatural-meets-Gothic setting. Both of these plays were written and produced around 1990. I was amazed, on a 2018 visit to Cape Town, to be approached by a South African student who told me they were studying it as part of their graduate program. Yet, my West African Gods inspiration in turn fizzled out: the dialectics of superheroes, whether mythological or comic-based, would not be denied, and the contradictions of Exceptionalist superheroes and my Collectivist politics were irreconcilable.

My writing became countercultural, anti-heroic. The first short story I had published was a detective story, The Adventures of Maud Mellington Part 1: Dirty laundry (I never wrote Part 2). Its “hero” was a Windrush-generation former National Health Service nurse who was trying to cure the loneliness of the older West Indian generation of Manchester. I wrote a number of crime fiction stories featuring aspiring black cop Ambrose Patterson working in a racist force, along with a down-at-heel private detective, Delroy Johnson, doing wonderful things quietly to help out folks whose attempts to obtain justice by official means had been blocked by apathy and disinterest.

I leapt into sci-fi with my novel Black Star Rising, in which an all-black crew—traveling in a space-ship a thousand years from now—faced an extinction dilemma. And I wrote young adult fiction, giving wit and energy to young working-class voices of the North. I never thought I’d create a superhero again.

Then Comma Press came calling, claiming they had a formula to square the circle. They wanted stories of activist superheroes, based on historical British figures, who fought political crimes rather than the crimes that cops fight anyway. It was a compelling point of departure from the American superheroes of Marvel and DC Comics. I dug around in archives and found English history was replete with working-class heroes and social justice movements which had figureheads of collectives of ordinary radicals: working-class folk who resisted unjust authority or rebelled against outright tyranny.

Such was the case in 1797 on the ship, The Hermione, site of the bloodiest mutiny of British history. The mutiny took place around the time of revolutions: the 1791 Haiti Revolution, the 1789-99 French Revolution, the 1765-1791 American Revolution. Revolution was everywhere, including at sea. So, I invented my superhero “Hermione”—with the help of historian, Niklas Frykman—(her catch-phrase: “until my last breath, they shall breathe too”) and dedicated the story to the ship Hermione’s brave, downtrodden, from-all-parts-of-the-world crew, who, all those years ago, had dared to combine, resist, and rise up against their despotic English Captain and his lickspittle officers.

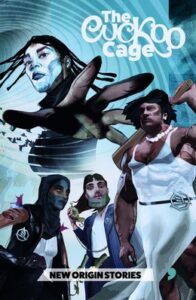

In the 21st century, we are wisely wary of superheroes. They can very often turncoat and transform into villains. But if we have to have them, then the superheroes contained in The Cuckoo Cage are the best around.

__________________________________

Pete Kalu’s story “Hermione” features in The Cuckoo Cage: New Origin Stories, published by Comma Press, February 2022. Available to buy here. Top image: “SuperHero” by ‘J’ Jose Maria Perez Nuñez.

Peter Kalu

Peter Kalu is a poet, fiction writer and playwright. He cut his teeth as a member of Manchester, UK's Moss Side Write black writers workshop and has had nine novels, two film scripts and three theatre plays produced to date. He gained his PhD in Creative Writing, Lancaster University, UK, in 2019.