What Can Bruce Lee Tell Us About Our Contemporary World?

Daryl Joji Maeda on How the Historical and Political Forces of the Late 20th Century Made a Cinematic Icon

In the climactic scene of Bruce Lee’s final film, the 1973 martial arts movie Enter the Dragon, Lee pursues the archvillain Han with the hope of finishing their fight in a hall of mirrors. The two stalk each other through the maze of reflections and refractions, the screen filled with one Lee, two, a dozen, or none at all, as he slinks in and out of the frame. Some of the images are complete, others only fragmentary slivers.

The multiple Lees always move in unison, sometimes in the same direction, sometimes toward or away from each other. A distorted image of Han lies in wait for Lee and strikes him in the face with a backhand blow. Lee swings back at the reflection but finds only air as Han retreats invisibly farther into the funhouse.

As Lee moves forward, his back to the camera, Han emerges from the reflections and slashes Lee on the shoulder with a bladed claw before disappearing again. The camera alternately captures images of Lee and Han reflected in long mirrored panels that break them up into a dozen overlapping images. Tension builds as the viewer is never sure of whether the image onscreen is the real Lee or a mere reflection. The fragmented Lee delivers a side kick that sends a dozen Hans flying, after which the real Han rolls across the screen.

Lee, frustrated by his inability to locate his foe, backs up against a set of mirrors as a voice-over of his sifu (teacher) intones, “Remember, the enemy has only images and illusions behind which he hides his true motives. Destroy the image, and you will break the enemy.”

The figure of Bruce Lee remains as elusive and contradictory in real life as he was in that hall of mirrors on the big screen.

Inspired by this brief philosophical refresher, Lee delivers a backhanded fist to an image of Han, in the process splintering the mirror containing Han’s reflection. Using fists and feet, he shatters mirror after mirror until he can move forward confidently, for the shards of broken glass reveal the falseness of the Hans they reflect and leave the true Han visible and vulnerable. Lee rushes triumphantly toward the exposed villain and side-kicks him across the room, impaling him on a spear protruding from the wall.

According to Robert Clouse, the film’s director, the hall of mirrors scene was not included in the original script but was dreamed up by him and his wife. The set consisted of a large room paneled completely in mirrors. Three shallow bays, each about five feet wide, were covered with narrow vertical slats of mirrors that created dozens more reflections. The camera sat inside a mirror-covered box about six feet square in the center of the room behind a mirrored sheet of plywood with a cutout for the lens that enabled it to shoot anywhere without capturing its own reflection.

Some $8,000 worth of mirrors—two truckloads’ worth—were used to construct the set, an undertaking that took three days. The scene, which lasts for just five minutes in the movie, took two days to shoot. Clouse claims that after filming on Enter the Dragon ended, Lee spent two more weeks in Hong Kong, where the film was made, shooting additional scenes on the mirrored set.

In many respects, this intricate scene represents the complexity of both Bruce Lee’s life and his career. Never before had the entire world had a chance to see Bruce so clearly, but Enter the Dragon elevated his profile to unimaginable heights. Though he was already Hong Kong’s biggest movie star, his final film hit occupied the top spot on the United States box-office chart for three weeks and took in more than $90 million worldwide.

But just as the images of the fictional Lee seesaw between reality and illusion, unity and multiplicity, perception and deception, the figure of Bruce Lee remains as elusive and contradictory in real life as he was in that hall of mirrors on the big screen. Hometown hero or global icon, Chinese nationalist or universal humanist, disciple of kung fu or heretic, ascetic or hedonist, devoted father and husband or playboy: the iconic martial arts practitioner and pop-culture hero vacillated between being all of these and none.

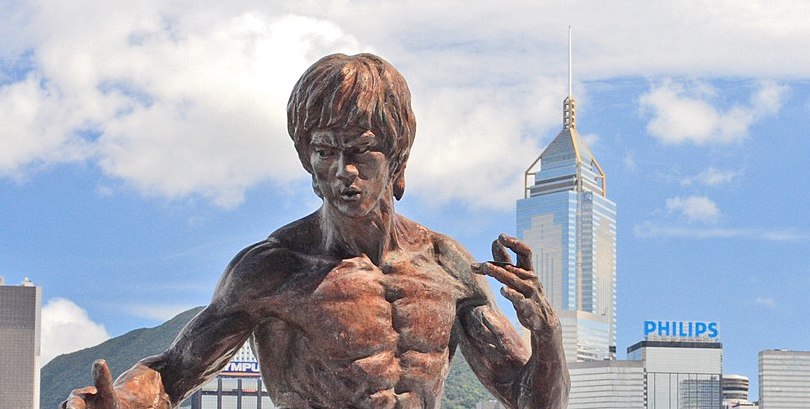

Take, for example, the question of what country can rightly claim him as its own. Hong Kong loves its native son, who grew up in the colony and in the 1970s became the first global Chinese superstar. A bronze statue of the martial artist and actor holds pride of place on the Avenue of Stars on the Kowloon waterfront, where tourists flock to strike martial arts poses for photographs framed by the blue waters of Victoria Bay and the soaring downtown skyline. The Bruce Lee: Kung Fu, Art, Life exhibit mounted at the Hong Kong Heritage Museum in 2013 told the story of a local boy and child movie star who learned Wing Chun style of kung fu and fought atop rooftops, decamped to the United States for a few years, then returned to Hong Kong to become Asia’s biggest movie star and win worldwide acclaim.

Within the turbulence of people, cultures, and identities roiled by transnational capitalism and militarism, Lee combined Taoism and Western philosophies.

Chinese America also loves its native son, who was born in San Francisco in 1940, worked as a busboy in a Chinese restaurant while attending a technical school in Seattle, developed a reputation as a martial artist in Oakland, and struggled to make a name for himself in Hollywood. On the Bruce Lee walking tour of Seattle, sightseers visit the playground where the young martial artist worked out and dine on his favorite dish of beef with oyster sauce at Tai Tung, his favorite Chinese restaurant.

The Do You Know Bruce? exhibit at the Wing Luke Museum in 2015 traced Lee’s Seattle roots and stressed his development as a martial artist, teacher, and actor on the US West Coast. Yet neither of these two competing local stories—of a Hong Kong boy who ventured out into the world or a Chinese immigrant struggling to make it in the United States—captures what is most compelling about this iconic figure.

As the often riveting details of Bruce Lee’s life reveal, his story is endlessly fascinating, and for many different reasons. He became a global phenomenon due to his incessant traversals across the Pacific, a vast region across which peoples of various nationalities, races, and cultures have confronted each other as adversaries, trading partners, and neighbors over four centuries. Transpacific migrations shaped Lee and his world.

Movements and migrations across the Pacific Ocean structured the histories and cultures he inherited, the milieu he occupied, the martial arts practices he developed, the films he made, and the world that he left behind after his death in Hong Kong on July 20, 1973, a year that will also be remembered as the one that witnessed the Yom Kippur War, the Arab oil embargo, and the start of the Watergate hearings in Washington, DC. Lee’s death, blamed on an overdose of a prescription pain killer, was officially ruled “death by misadventure,” which in turn became the title of a 1973 documentary about Lee’s turbulent life and times. He was thirty-two years old.

The conditions that enabled Lee to become an icon celebrated around the globe were created by a variety of forces—European and US trade with China in the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries, the British colonization of Hong Kong in 1841, the discovery of gold in California in 1848, Cold War deployments of US troops throughout Asia in the last half of the twentieth century, the counterculture of the 1960s, and Lee’s own incessant shuttling between Hong Kong and the West Coast of the United States until the abrupt end of his richly multifaceted career in 1973.

Bruce Lee’s story is a quintessential illustration of how larger forces have shaped an increasingly globalized world.

Within the turbulence of people, cultures, and identities roiled by transnational capitalism and militarism, Lee combined Taoism and Western philosophies; synthesized fighting styles from China, Japan, Okinawa, the Philippines, Korea, and the West; and blended Hong Kong and Hollywood cinema to create a fusion all his own. He pioneered new ways to use the body as a weapon, advocated martial arts as a path toward harmony among strangers, and articulated interlinked critiques of colonialism and racism.

*

Bruce Lee’s colorful and dramatic story is worth examining for a number of important reasons. Because Lee embodied the transpacific flows of people, culture, and ideas that began in the sixteenth century and have accelerated ever since, his story provides a lens through which to understand how peoples confront each other, intermingle, and produce wondrous new cultural forms and alliances in an era of globalization that itself confronts continuing inequality, racism, and xenophobia.

Bruce Lee’s story is a quintessential illustration of how larger forces have shaped an increasingly globalized world. Lee was an extraordinary person, to be sure, but his story could not have unfolded at any other moment in history. The forces of mercantile capitalism, colonialism, Cold War militarism, and globalization fundamentally reordered the world in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, giving rise to the intricately intertwined and thoroughly transnational planet we inhabit today. Humans have crossed geographical and political boundaries since time immemorial but never at the pace and frequency seen in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Migrations and contacts, whether friendly or belligerent, produce new forms of culture. Whenever peoples meet others whom they consider to be different from themselves, regardless of whether the distinctions are drawn along tribal, ethnic, religious, or national lines, they exchange, adopt, adapt, co-opt, and incorporate ideas, beliefs, technologies, and cultural practices and create new identities.

As the Roman Empire grew through conquest, it not only spread its religion throughout Europe and Africa but also incorporated new local deities that coexisted alongside the old gods. The Manchus who conquered China strategically embraced the native ideology of Confucianism as an instrument of rule. What could be more English than tea served in a fine China pot? Yet both the beverage and the vessel that typify Britannia originated in China.

It is impossible to imagine US music or world music for that matter—jazz, rock-and-roll, hip-hop—without hearing the voices of enslaved African peoples. The borderlands of the Southwest of the United States boast a unique hybrid culture that combines Mexican, Spanish, Indigenous, and European influences and, where these borderlands abut the Pacific, Asian influences as well. Where could the Korean taco have emerged except in Los Angeles?

___________________________________

Excerpted from Like Water: A Cultural History of Bruce Lee by Daryl Joji Maeda. Copyright © 2022. Available from NYU Press.

Daryl Joji Maeda

Daryl Joji Maeda is Dean and Vice Provost of Undergraduate Education and Professor of Ethnic Studies at the University of Colorado, Boulder. He is the author of Chains of Babylon: The Rise of Asian America and Rethinking the Asian American Movement.