What Are We Getting Out of Mythology?

Seamus Sullivan on Honesty and Mercy in Reading Myths

I must have been in grade school when Ingri and Edgar Parin d’Aulaire presented me with a death scene so visceral I carried it with me to adulthood. King Minos, conqueror of Athens and stepfather of the Minotaur, has traveled to Sicily in pursuit of Daedalus, his chief architect and erstwhile prisoner. At the invitation of the king of Sicily, Minos takes a bath in his host’s palace, as is traditional. “But,” the d’Aulaires informed me, “when he stepped into the fabulous bath that Daedalus had built, boiling water rushed out of the tap and scalded him to death.”

The brutality of Daedalus’s revenge struck me. Here was an artist, a father, murdering someone with a viciousness that went beyond self-preservation. As if Minos inspired such hatred, such fear and disgust, that the feelings themselves boiled up from Daedalus’s heart and gushed out through the tap to cook the wicked king alive. I didn’t know what it was like to hate someone that much.

Now, as a grown-up writing for other grown-ups in 2025, I think I can say that all but the most saintly among us know what it’s like to hate someone that much.

Every rule, every value, was created by the consensus of adults, and adults will discard those rules and values when it suits them.

There are other resonances in the Daedalus story that I can’t unsee now, at this halfway point in a pretty tough decade, the decade in which both of my sons were born.

The scalding becomes a metaphor for stochastic violence. The depersonalizing power of technology makes it easier to spray hatred at someone from a distance. Substitute broadband for indoor plumbing. Going back to the beginning of the story, the Minotaur becomes a metaphor for America’s willingness to designate whole groups of people as human sacrifices, whether they’re COVID victims, our disproportionately huge prison population, or residents of Gaza and the West Bank. The Labyrinth becomes a stand-in for the kind of technological know-how that can make sacrificial populations disappear without Americans having to see it directly. Consider, for example, the usefulness of Microsoft’s cloud service when targeting Palestinians for mass surveillance, arrests, and air strikes. Or US bombs falling on Gaza. Or US missiles hitting Yemen. Or drone strikes in Afghanistan. Or “shock and awe” in Iraq.

A lot of these connections emerged in hindsight, helped along by the passage of time, and possibly depression-induced apophenia.

Years ago I went on some dates with a playwright who wanted to explain The Mahabharata to me. You could, she told me, fit both The Iliad and The Odyssey, combined, into The Mahabharata many times over.

“Your western epics,” she said, mock-patronizing. “So cute.”

We’re married now, so the negging worked.

I asked my wife recently how her relationship with The Mahabharata had shifted since childhood. Madhuri thought about it, then said that the prevailing takeaway, as she got older, was “that adults were full of shit.”

In the cataclysmic civil war at Kuru-kshetra, both the divine Pandava brothers and their treacherous cousins, the Kauravas, end up breaking the rules of war to achieve victory at any cost. Abhimanyu, the teenaged son of the great archer Arjuna, dies at the hands of his own uncles and cousins, flanked on all sides and hopelessly outnumbered. Mighty Bhima, strongest of the Pandava brothers, defeats Duryodhana by breaking his thighs and crushing his genitals with his mace, literally hitting him below the belt. The remnants of the defeated Kauravas sneak into the camp of the victors at night and kill the children of the Pandavas as they sleep. The cost of victory turns out to be everything.

Every rule, every value, was created by the consensus of adults, and adults will discard those rules and values when it suits them.

Here’s another image from the D’Aulaires, a drawing this time, right at the confluence of cute and bloodthirsty so beloved by kids of a certain age. Echidna, mother of monsters, here depicted as a greenish, redheaded snake woman, hides from the Olympians in a cave. Climbing her body, suckling, and helpfully labeled by the authors, are adorable baby versions of six great monsters of Greek mythology: the Nemean Lion, Cerberus, Ladon the many-headed dragon, the Chimera, the Sphinx (with the nubs of two precious little baby wings emerging from her back), and the Hydra.

At three, my eldest son loved this drawing. (To this day, he pretends to be baby creatures: a newly-hatched velociraptor, or a squid “the size of eight pennies.”) His favorite Greek myths were all creature-related. He often wanted to hear about the mechanics of Bellerophon’s confrontation with the Chimera, or Heracles’s defeat of the Hydra.

He found his favorite story, by far, on a trip to visit grandparents in Chennai, where we bought him an Amar Chitra Katha comic depicting the boyhood adventures of Krishna. If you are mythologically inclined and have a small child to entertain, you will not find anything better than these stories, in which the divine little boy beats the ever-loving tar out of a series of demons and monsters. The crown jewel, for our son, was Krishna’s encounter with the hundred-and-one-headed snake, Kaliya.

Krishna discovers that Kaliya is living beneath the surface of a local pond and poisoning its waters with his venom. Venturing into the water to do battle, Krishna grows in size to escape the snake’s constricting coils. When Kaliya spits fire, Krishna dances across its many heads, crushing them. Where many of Krishna’s battles end in death for the aggressor, this story is remarkable for its mercy—Krishna spares Kaliya after the snake’s wives and children emerge from the pond to plead on his behalf.

That summer we played Kaliya every day. Inevitably, someone ended up swinging a quilt around to mimic the great snake’s darting heads and churning coils.

Now five, our eldest son loves creatures more than anything. He loves Brachiosaurus and the cookie-cutter shark, Anomalocaris canadensis and the giant ground sloth, spiders and crows and every variety of squid and octopus. Snakes remain a favorite. He is distressed when people step on insects, and he intercedes with other kids who are about to stomp.

I wouldn’t say Kaliya inspired all this (The Magic School Bus and the Kratt brothers have more to do with it), but I do credit the great snake for my son’s early flicker of self-knowledge, his recognition of nature’s vastness and strangeness, the vulnerability of its creatures, their need for his curiosity and his love.

We don’t know our youngest son’s favorite myths yet. We don’t know which myths will take on new meanings for our boys, when they’re closer to our age.

Our youngest son was a baby when his big brother encountered Kaliya. Now that our youngest is old enough to voice his own opinions, we aren’t reading as much mythology. Like Hyperion and his Titans, the creatures of myth have been overthrown by young upstarts: Hallucigenia, Tyrannosaurus, axolotls, flying geckos, polar bears. We don’t know our youngest son’s favorite myths yet. We don’t know which myths will take on new meanings for our boys, when they’re closer to our age.

Here’s what I do know. Stories that acknowledge and commemorate sadness and loss are a psychological necessity, particularly if you are living through years in which great sadness, loss, and moral injury are taking place, and especially if you are living under a corrupt political system and a supine press establishment, both of them loudly proclaiming, with lies of commission and omission (as with COVID, as with Gaza, as with climate change) that you have nothing to feel sad about.

It is a given, I fear, that my sons will experience great sadness, that they will see things come to pass that should never come to pass. They will learn that adults are full of shit.

I hope that the myths we’ve read together, and the myths they’ll seek out on their own, will help them hold on to some honesty and some mercy, in the face of what’s coming. I hope they’ll find like-minded friends and loved ones—myth people, book people, creature people—peers and confidantes who also believe in honesty and in mercy, however loudly certain voices continue to insist that those things are as fanciful as a Pegasus, or a Chimera.

__________________________________

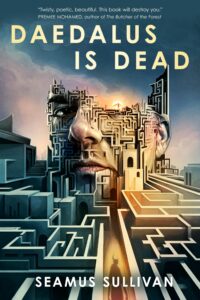

Daedalus Is Dead by Seamus Sullivan is available from Tordotcom, an imprint of Macmillan.

Seamus Sullivan

Seamus Sullivan’s fiction has appeared in Terraform and his book reviews have appeared in Strange Horizons. He lives in Jersey City with his family. Daedalus is Dead is his first novel.