We’re Not Promising Anymore: Lizzy Goodman on the Fleeting Amateur Spirit of Meet Me in the Bathroom

“You have to make your story out of what you find.”

This conversation is presented in partnership with the Refocus Film Festival, a four-day celebration of the art of adaptation and hosted by Iowa City’s nonprofit cinema, FilmScene. The 2nd annual Refocus Film Festival will take place in Iowa City October 12-15, 2023. Passes are on sale now, with individual tickets and full festival announcements coming in September.

*

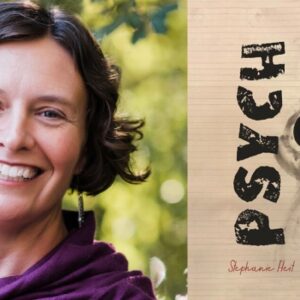

Spanning nearly 600 pages and over a decade of music history, Lizzy Goodman’s Meet Me in the Bathroom: Rebirth and Rock and Roll in New York City 2001-2011 is an oral history that chronicles the resurgence of rock at the turn of the millennium. Featuring members of seminal bands of the moment such as The Strokes, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, and LCD Soundsystem, as well as journalists, bloggers, and industry professionals, Goodman has crafted a sprawling narrative of nostalgia as intimate as it is intoxicating. It’s a story as much about the mythic idea of New York as New York itself, a collective recollection of a changing American landscape that is more loyal to immersive feeling than linear fact in the best, most impacting way. The book was adapted into a documentary of the same name in 2022, directed by Dylan Southern and Will Lovelace, and on which Goodman served as an executive producer.

I sat down with Goodman over Zoom to talk about what lies at the heart of nostalgia and how she navigated those complexities as she crafted her opus. What follows is a one-sided excerpt of our conversation, edited for clarity and concision, to serve as a thematic and emotional primer for both the book and the movie.

Lizzy Goodman: There tends to be a kind of “everything was better in the past” element. There can be, there’s a temptation to go there. And when you’re choosing to spend time in and focus on a particular period that’s in the recent past, you kind of glorify it. Inherently. I think that’s inevitable, but I’m really glad it doesn’t feel cranky. There’s nothing less attractive than people bitching about how much better things were in their era, and I really don’t subscribe to that.

In terms of figuring out what, if anything, I did to guard against that [brand of nostalgia], I’d say that I didn’t think about it. What I did was not let people talk about it in the book. To your point about controlling and not controlling exactly what’s in here, on the one hand you have total control, and on the other hand you can’t print anything that somebody didn’t say to you. So the material is found, in that sense. It’s initiated or invited in various ways, but you cannot create it. You have to make your story out of what you find.

I got lots of quotes from people feeling everything from sad to resentful to enraged to imperious about what we’ve lost and how the city used to be and what people don’t get, what kids today don’t get, yada yada yada. I used a kind of golden rule, a kind of measuring stick for what got in across the board. I always have this image of myself holding a slide that represents the piece of dialogue up to the light and going, Does this serve my story? And if it doesn’t, throwing it over my shoulder onto the cutting room floor. In that sense, it was simple. Not easy, but simple.

I always have this image of myself holding a slide that represents the piece of dialogue up to the light and going, Does this serve my story?Now I feel like I’m giving advice, which isn’t really what you’re asking, but I feel like saying this, so I will: I did not know how to write an oral history. I didn’t study it. I don’t have an MFA. I didn’t study creative nonfiction. I didn’t study creative writing outside of college in any meaningful way. The thing I really held to, and that I think you can always hold to, is this. You’re here because you see something in this, you see something that you’re trying to make manifest to others, you see a story. And just serve that. Like religiously, unrelentingly serve that. You’ve got to labor for that story. I didn’t think outside in, like, I need to really protect the story from X, Y, or Z derailment. I thought, What belongs to my story? What belongs to my story? What belongs to my story?

To return to part of what we were talking about before, in service of the question: what’s the difference between evolution and death? I think part of the reason I didn’t find myself drawn to the conversation around better-in-our-day-ness is that there’s nothing more eternal than being a person who used to be young and thinking that your youth was the superior version of the experience of coming of age. It’s how it’s supposed to feel. People ask me now in interviews, what do you think of New York’s current music scene? I’m like, Dude, I have no idea [laughter]. And how disturbing would it be if I did?

It’s supposed to be fleeting. It’s part of its beauty, the fragility of it, the ephemeral nature, the sense of living through something ecstatic and fundamentally temporary. And knowing that you’re not going to understand it in full while you’re living through it. That’s the whole gig. That’s what it is to be a person of coming-of-age age, the post-teen into early 20s era where you’re trying to figure out who you’re going to be as an adult. Who am I going to be in the world? Who are going to be my people? What is the language of myself? And in this case, as in many cases before and many cases since, New York as an idea is the backdrop, the setting for that process. And “New York” can exist in London or Omaha or Adelaide.

The whole point of that process is that it’s supposed to feel like it’s not going to be there forever, and you’re even kind of aware of that in the moment, and you can’t do anything about it. That’s where the urgency comes in. It’s inherent that once that door closes for you, your [experience] is cast in amber.

I think, for me, evolution involves death. To have something change is to lose what it was. And in that moment, that inciting incident was very much a sense that everything I just described, the kind of ecstasy of my early twenties and many of my friends’ early twenties, my relatively private coming-of-age story set in the city involving these bands, involving this sense of self-discovery and transition from desire and ambition to fucking doing it, to practical, real world action, that cycle had happened. And it was over, that part.

When I was a kid, my father, he had this line. He had these two best friends as a young man, and they traveled together in England after college, and they had all these young person experiences. And then one of them turned to my dad and said, Russell, we’re not promising anymore. And it’s just like, ugh! Right? But also, okay. Because that death of promise is the thing you’re trading on. That’s what that moment felt like: my friend’s band is onstage playing Madison Square Garden for famous people. For adults. For grownup humans who probably have savings accounts and other unimaginable things [laughter]. That world understands this world, recognizes it, and bought tickets to it. And that felt like a death, in a way, of that promise period. But it also felt incredibly exciting. It felt, yeah, elegiac, you used that word. There’s a sense of sorrow, a sense of wistfulness, but it was also exciting because it was like, I cannot believe we pulled this off. Is this real? Like, that’s Susan Sarandon watching LCD Soundsystem. She’s really cool. And in good movies. What is happening?

I’ve obviously had cause to think quite a lot about why Meet Me in the Bathroom as a book, but also as a container, a way of naming a certain period of time, has connected with as many people as it has. I think my generation’s immediate version of this thing, what makes it unique, is that our private world became this stand-in for this experience. I think what happened is really normal. I can use all these banal words: standard, basic, what’s supposed to happen. It’s just how it feels to be that age. And I also think our particular version of it had all these external extenuating circumstances that conspire to create a kind of supernova version of this thing everybody has some relationship with. It becomes a kind of avatar for this particular type of experience, of finding yourself and your people, and then discovering you’re not promising anymore.