Brando Skyhorse on the Fantastic Art of Revision

"Are we no longer confused?"

This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

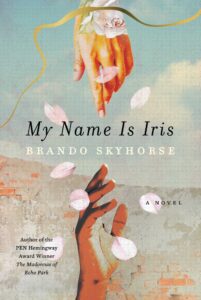

About seven years ago, I started a novel called La Niña, about a single woman named Maribel Nava who finds a baby left on her doorstep. This month, I published a novel called My Name Is Iris, about a just-divorced mother named Iris Prince who wakes one morning to a wall that has appeared in her front yard overnight.

These projects are, in fact, the same book.

How did this happen? The answer: revision, or the fantastic art of throwing out what doesn’t work, and keeping what does.

I’m evangelical about revision because a) it costs the writer nothing except time, which is already an essential part of the writing process, b) it keeps hidden all the writer’s early, terrible drafts (except when they’re excavated in tiny pieces for essays like this) and c) it’s the only way I know to see meaningful progress in a written work. It makes bad writing better, transforms incoherence into competence.

Most times when I write, I do not understand what I am trying to say on the page. Something gets lost in the journey from the place where I think about what I want to say, and then saying it. Over the years, I’ve collected some bullet points on revision that have helped me figure out what I mean when I sit down to write. I can’t fit all of them here, but these are the most important ones. Maybe they’ll help you, too.

• Does each of my characters want something? Is what they want clear within a page of their appearance?

This was the biggest problem with La Niña. I did not know Maribel well enough to understand what she wanted. A catalytic event happened to her, and she reacted to it. The challenge with reactive characters is that they are too busy reacting to what a writer puts in front of them—and writers are so busy thinking of new things for them to react to so we can keep the plot moving—that what they really want can get lost in the process. A character should demonstrate what they want within a page of the reader meeting them.

In My Name Is Iris, Iris likewise has a major inexplicable event happen to her, but we learn this event is, somehow, a manifestation of her desire not to stand out, for security, anonymity, and belonging. Iris is a Mexican-American woman who has just initiated a divorce (her action, based on her desire) and has moved into a new suburban community with her child. She wants to blend in, nice and easy. This wall—and other events in the novel—won’t let her. She reacts to these events, but her agency initiated the chain of events. Her desire to hold onto her new home, and her new life, forces her to act throughout the novel. Clear desire equals action.

• Avoid using clichéd actions to describe what a character is doing, saying, or feeling.

A baby left on the doorstep is one of the oldest plots in fiction. I knew this when I started La Niña, but I didn’t have any better ideas, so desperation let me ignore how lame this device was. To work around this contrivance, I paired it with a what-if idea: what if a successful Constitutional amendment referendum stripped citizenship from every American who cannot prove at least one parent is a US citizen? (This idea, too, was cribbed, from a piece of legislation proposed by a former US Senator who was later outed as a client of a DC-based escort service.) I wasn’t sure how these two ideas fit together but I kept kicking them around together in clunky drafts for a year or two that started like this:

Three days after the election, Maribel Nava found a sticky, pink-skinned baby in an oblong Amazon box on the porch of her two-bedroom tract home.

Not terrible, but… eh. A cliché is a cliché, no matter how you write it. The same goes for shrugged shoulders, nodding heads, and characters who smile or shrug in dialogue, though as it turns out, only Richard Russo can get away with that. (See Benjamin Dreyer’s phenomenal Dreyer’s English: An Utterly Correct Guide to Clarity and Style.)

Revision is a change in perspective. It’s not spell checking, or changing “red” to “crimson.” It’s about changing your point of view of your story.

Changing your perspective on your work is the most important thing that can happen to it. This change can happen in a variety of ways: practical, emotional, psychological. For me, it involved moving into an old farmhouse in the summer of 2016. The house was too big, meaning I had lots of time to read the daily news and stare out the window. That summer, one word dominated the news cycle: wall. I heard it everywhere. It had ceased being a dead noun and instead became animated, alive. It was the inflexible punch of an advertising slogan, the spike at the end of an infectious chant. One breezy morning, I looked out my window and stared at a long, stone wall ambling through a green pastoral field. I don’t know how long I was staring but I heard a voice say, “It’s growing! Can’t you see the wall is growing?”

That was my introduction to Iris Prince.

As I became more familiar with Iris’s voice, the baby on the doorstep contrivance disappeared, and I began to focus on who Iris was, and what her desires were. She desired “security” for herself and her daughter above everything else and, as such, had many thoughts about the Constitutional amendment referendum from La Niña. That idea stayed, morphing into a high-tech wrist wearable launched by a Silicon Valley startup called “the Band.” In the novel, the Band is pitched as a convenient, eco-friendly tool to help track local utilities and replace driver’s licenses and IDs, but is available only to those who can prove parental citizenship. Iris doesn’t qualify, meaning her goal will be to figure out where she fits in this new “reality,” with “the Band” forcing her to act/react on one end, and a mysterious wall that won’t stop growing on the other.

After two-plus years of aimless searching, I had a new voice that told me who it was and what it wanted. I had some ideas that felt unique enough for me to pursue. I had a couple of grainy images of where the novel started and ended. I even had a new book title—“Wall”—that lingered for most of the novel’s years-long composition until I realized that word—wall—might be selling my main character Iris Prince short. The same way that word has sold a lot of people short. Maybe this book was about something bigger than a wall instead.

• Are we no longer confused?

The book took nearly seven years to figure out. I say “figure out” instead of “write” because much of that time wasn’t spent writing, but revising—and thinking about—what I had written. The “we” here are your readers, those souls fortunate enough (or not!) to tell the writer what still doesn’t make sense on the page. Maybe you have a long-suffering partner who continues to read your endless drafts and endures rounds of defensive questioning when they try to explain what remains unclear to them. You’d be amazed at how often a writer says, “What I meant to say…” and offers a perfect explanation about what should be happening on the page, but can point to no written words that illustrate what they just described.

Don’t just think it—write it down.

This month, I published a novel named My Name Is Iris. This is its first line:

Whenever I ask my mamá what her first memory of America was, she says, “Who cares about me? You were born here.”

This is the story I arrived at after six-and-a-half years. Revising is how I got there. I couldn’t have written it any other way.

______________________________________________

My Name Is Iris by Brando Skyhorse is available now via Avid Reader Press.