'We're Looking at a New Cold War': A Conversation with Daniel Yergin

Bill Cohan Speaks to the Author of The New Map

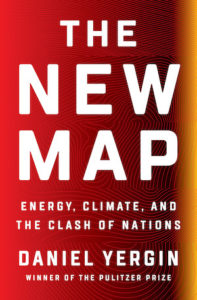

For decades, Daniel Yergin’s Pulitzer-winning book The Prize has been the go to guide to understanding the history of oil exploration, from 1850 up until the near turn of the century. Obviously, the past 30 years have seen enormous, even catastrophic changes to the landscape. Fracking has altered the land and also changed the global balance of power. For the first time in years the US is the world’s largest energy producer. In The New Map, his most revelatory book in years, Yergin addresses the ways a new geopolitical power game has been set off by energy production in the 21st century. He sat down and spoke with his friend, the writer William D. Cohan, about what his new book says and how, as a writer, he put it together.

*

Bill Cohan: Dan, I do want to talk to you about writing. You’re known for your talent for narrative. One review of an earlier book called you “a marvelous storyteller.” A reviewer of your new book, The New Map, calls it a “page turner.” But before we talk about writing, let’s talk about the book itself. It is really timely. It deals with issues that are at the forefront of the presidential campaign. But to begin with, what is this new map?

Dan Yergin: It’s a map that provides a guide through disruption. It’s about energy, but it’s also about our society, how we live and will live. And it’s very much about geopolitics and the clash of nations. And right now the clang of that clash is growing louder. I think we need to hear it.

BC: Speaking of that clash, in the book you talk about how Russia and China, our two largest nemeses, are forming a deeper alliance. They each call each other their best friends now or whatever, and our relationship with them continues to deteriorate. You go so far as to speak of a new cold war.

DY: We are looking at a new cold war. My first book was on the origins of the Soviet-American Cold War. I never expected to be writing a book about new cold wars, but as I was writing The New Map, it was becoming clearer to me that a new cold war was brewing between the US and China, and in the last few months that’s accelerated.

As I was writing The New Map, it was becoming clearer to me that a new cold war was brewing between the US and China.

The reality is that the world of open trade, open commerce that seemed to be the world after the end of the Cold War is over, and we have gone from an era of openness and travel and so forth to one of strategic rivalry and great power competition. I was very struck last year when I was in St. Petersburg at a conference, watching Presidents Putin and Xi—Putin apologizing for keeping Xi up so late talking, and Xi saying, “We never have enough time to talk.” I think they have a lot to talk about, including their common opponent, the United States.

BC: How does energy play into the increasingly tense geopolitical dynamic between the two countries?

DY: The South China Sea may seem very remote to a lot of people, but it’s the most important trade route in the world. It happens to be the route by which China, which imports 75 percent of its oil, gets much of that oil. The Chinese have been preoccupied for decades with the possibility of the US Navy interdicting their oil supplies, if there’s a standoff over Taiwan or something else.

The Chinese have responded by claiming that the South China Sea is actually Chinese territory. The United States and the other nations that abut the South China Sea do not agree. I describe in the book specific incidents of US and Chinese naval vessels almost colliding and US airplanes being challenged by the Chinese. I think any reader of the book will expect more of that to happen.

BC: One of the big components of the new map is the United States’ becoming far less dependent on imported oil, largely because of what we call fracking. So what are the myths and the facts about fracking?

DY: It’s really changed the map in so many different ways. The United States is now the world’s largest oil producer, ahead of Saudi Arabia and Russia, and not the largest importer that it used to be. Fracking or the shale revolution has been much more transformative and has had a much bigger impact in many ways than people would think.

When it first appeared on the scene about a decade or so ago, there was a discussion, about the environmental impact. I was on the committee that President Obama set up to look at the environmental impact, and the conclusion was this is an industrial activity. If it’s properly regulated, it’s a big plus, and it has been largely well regulated.

What people don’t understand is all the other impacts that it’s had. It’s been a major stimulus to the US economy. It created, before this downturn, literally millions of jobs. It’s been very important for manufacturing industries.

It’s changed our balance of payment, and it’s had a major impact on the role of the United States in the world. A prime example is Iran. Whether you support President Obama’s approach or President Trump’s approach to Iran or what would be President Biden’s approach, none of that would be possible were it not for the flexibility that comes from our being the world’s largest producer of oil and natural gas.

The Stone Age didn’t end because we ran out of stones. And the oil age isn’t going to end because we run out of oil: it will be because of technology.

The Iranians thought the original Obama sanctions would never work, because they though the oil market couldn’t take it. What they didn’t realize is their oil would be replaced by our oil. Shale has also brought significant income to poor rural or semi-rural communities.

BC: Where does this leave the Middle East and Saudi Arabia, the traditional major oil suppliers?

DY: The world oil market is no longer OPEC versus non-OPEC. It’s the Big Three—the US, Saudi Arabia, and Russia. We saw this past April the US brokering a deal to stem the oil price collapse that came with the COVID shutdown.

BC: One of my favorite expressions of all time is the Stone Age didn’t end because we ran out of stones. It means the oil age isn’t going to end because we run out of oil.

DY: When it ends, it will end because of technology. I did a study with Obama’s former energy secretary, Ernie Moniz, for Bill Gates and tech investors about the technologies that you actually need for an energy transition. We don’t have those technologies. You’re not just going do it all with wind and solar. By the way, wind and solar don’t power cars and replace oil. Wind and solar compete with gas and coal and nuclear to deliver your electricity.

BC: What’s your view on when this energy transition will take place?

DY: I spent a lot of time researching and thinking on that question for The New Map. It’s more like an energy evolution. The direction is clear. I think we’ll have an increasingly mixed energy system. We’re certainly going to see more renewables. But a lot will depend upon are those really big breakthroughs in technology.

BC: The photos in your book are incredible. What does it mean for the whole new map thesis of your book?

DY: The pictures are integral to the story. Here’s an example. There’s a great photograph of China’s president Xi Jinping taking his entire politburo over to a museum and standing in front of an exhibit about what they call the “century of humiliation.” Understanding that narrative is one key to understanding how China sees the world today—and how it comports itself.

BC: Put that in a larger context.

DY: “Map” is of course metaphoric. But also literal. The battles over the future of the Middle East go back to a map that an Englishman named Mark Sykes and a French diplomat Francois Georges-Picot drew up in the middle of World War I. That’s at the heart of many issues today. A different kind of map is the roadmap to the future and the possibility of overturning an automobile system that hasn’t really changed since Henry Ford started mass producing cars more than a century ago.The climate “map” is about how climate and how the politics would change dramatically with a Biden presidency and his $2 trillion climate program.

These are the organizing principles of the book, and it all comes together in this volatile interaction of energy and geopolitics.

BC: How disruptive has the COVID pandemic been? It’s been pretty disruptive for publishing.

DY: I know how challenging it has been for Penguin with everybody working at home and no meeting up in the hallway. Even under the very difficult operating circumstances, Penguin gave me the time to incorporate the world in which we now live, and I think the book catches not only the COVID curve but also the consequences. The chapter called “The Plague” describes the impact of the coronavirus on the energy system, geopolitics, and what I call the “economic dark age” of the shutdown.

Six years of digitalization have been compressed into six months. The nature of work has changed with big effects on commuting, on electricity use, and how people will travel. You see companies opening their offices, but asking people to avoid public transportation. Not easy to do in New York City.

BC: Do you ever think we’ll see a time that will be like what I saw, when I was growing and watching the cartoon series The Jetsons, where commuting was getting around on little personal flying jet cars?

DY: People are working on it. I spent time with a great innovator, Sebastian Thrum, one of the fathers of the self-driving car. He’s now working on the self-flying air taxi. So you may yet hitch a ride with the Jetsons.

BC: Let’s now talk about writing. How do you do it? You have a heavy agenda in your work and your other activities and travel. How do you find the time to write?

DY: I do do other things, but writing has been central for me since I was a child. It’s what I do. I can’t imagine not. There’s this persisting underlying urgency. My father had been a reporter in Chicago in the 1920s and 1930s and I was raised on what he would call his “newspaper stories.” He had all these writing projects when I was growing up, but they didn’t get anywhere. Somehow I took on the writing assignment.

BC: But your books take time.

DY: The way I think about is that you make a deal with yourself when you’re writing that unless something changes, you’re going to stick with the judgments and literary decisions you made a few years earlier. Of course, you’ll revise, update, test and retest. One of the enjoyable parts for me is editing and finely shaping a rough draft. I like that craftsmanship, and you adjust as you need to. You also have to trust yourself to depend upon this internal process to lead you through the narrative.

BC: Then do you plot out the book in advance?.

DY: I wish I could. That would be so much more efficient, but it’s never worked for me . . . For me, the writing is a process of not just research, but discovery—the stories, the gems, the connections you stumble over—and, really, an unfolding. What I do is immerse myself in one sub-part of the book and get my arms all around it and shape it and let the material tell me how it should be organized. Then I forget it, clear my mind, and move on to the next part.

BC: I’m laughing because that’s exactly what I do. I don’t understand these people who labor over outlines. As Hemingway said, “Leave a little bit, so you know what’s coming next,” what you’re going do the next day. Then you do that every day. But people think you have this book all mapped out.

DY: I can assure you that the book called The New Map was not mapped out in advance. I go where the story goes.

BC: And how do you actually write?

DY: My mother was a painter and I would watch her sketching when I was a child, building up the picture. I begin by sketching out in long-hand the picture before I paint it. I’m very visual. I see what I’m writing. I see the scene. I’m writing what I’m seeing. At least I think that’s the way I do it.

BC: But you’re traveling a lot and called to be in a lot of different places.

DY: I do—or rather did before COVID—a lot of traveling. But that gives me the opportunity to observe a lot, and that is in the book. But I didn’t want to use the “I’, the first person. I don’t say in the book that it was I who asked Putin a question, where he exploded in rage and he started shouting at the questioner, but that was me and he did start shouting at me, and being shouted at by Vladimir Putin in front of about 3,000 people is not exactly a pleasant experience. It’s tempting to use the “I” word, but it’s a literary judgment—that I shouldn’t use the first person if I’m trying to get that sense of historical sweep. For this kind of book, I think of the Victorian novel—the omniscient narrator. But, by the way, do describe the scene as vividly as you can.

BC: What are your other thoughts about narrative?

DY: One of the things I do believe in is the importance of voices, a lot of voices. Readers need to hear people. For the section on Tesla, for instance, you’ll hear and get to know the voice of the chief technology officer, who was just obsessed with electricity from childhood. You’re always looking for that quote that resonates off the page.

BC: So much of my time is spent on interviewing people, trying to uncover new things, literally the reporting, not just clipping things that other people have done.

I struggle with how to convey to the reader that I’ve actually done this reporting, that they’re actually getting something that’s novel here and important and worth their time, and not just something that I cut and paste from all these articles.

DY: That’s a really good question. Some people go very far with the first person singular. I think that question of how to introduce yourself into it probably depends upon the book, too. It may be for this book you’re now working on about GE, that it does make sense for you to set scenes where you can bring yourself in, but not in a heavy-handed way.

After all, what you’re really doing is uncovering a mystery, the mystery of what happened to what was considered America’s greatest corporation. That’s partly what writing is. Partly it’s solving a puzzle. It’s partly solving an equation, it’s partly solving a mystery. It’s partly bringing people alive. And it’s partly capturing the contingency of life..

BC: Is it true that you wrote this book in longhand?

DY: Absolutely. Always. How else? I write longhand because . . .

BC: Help me, god. I don’t understand how you do that.

DY: For me, that’s the sketching. I can stretch out on a couch, have it all in my head.

BC: You write on a couch?

DY: Yes, I’ll stretch out on a couch or in a chair, in a much more relaxed posture than sitting at a computer. At least I tell myself it’s a much more relaxed posture than sitting—

BC: Does that give you more permission in your brain to be relaxed?

DY: Yes. Or at least that’s what I believe. I find I get the pieces in place, and this flows into this and this flows into that.

But then the process of going from the handwriting to the computer is where—I hadn’t thought about it this way—I change hats and become my own editor as well as writer. Of course, at the computer you can keep playing with it and playing with it. Then I print it out so I’m working on hard copy. Once I’ve gotten it pretty much down. I usually read it out loud to myself: Does it flow? Does it sing? Does it have zing?

BC: I’m still amazed by the longhand.

DY: Not everybody is. A magazine for pen lovers, appropriately called Pen, was thrilled to hear that I write in in longhand, and they did an article about me. But, frankly, they were disappointed to find out that I do not write with a fancy fountain pen but rather with plenty of boxes of pens that come by the dozen.

BC: How do you marry the narrative with the facts to tell a story?

DY: My whole predisposition is that you’ve got to get to a narrative. Sometimes you can stop and explain something, but then, for your reader, you’ve got to get to the story and you’ve got to bring people into it, voices, and you need a sense of momentum and urgency to the narrative. So, at the end, you have to be true to the facts, but you also have to move with the facts.

BC: This book is somewhat unusual in that it traverses time periods.

DY: One of the challenges of this book is that I’m writing about the past, the present, and the future within the same framework. The past is what lends itself most to story, but the present does, too. But then how to write about the future in the same context. It’s a challenge. And this is a book about past, present, and future—all wrapped in the same narrative. The aim is to connect with the readers in a meaningful way. After all, their own lives are narratives.

__________________________________

The New Map by Daniel Yergin is available now from Penguin Press.

Bill Cohan

Bill Cohan, a former senior Wall Street M&A investment banker for 17 years at Lazard Frères & Co., Merrill Lynch and JPMorganChase, is the New York Times bestselling author of four non-fiction narratives about Wall Street, as well as The Price of Silence, about the Duke lacrosse scandal. He is a special correspondent at Vanity Fair and a columnist for the DealBook section of the New York Times. He also writes for The Financial Times, The New York Times, Bloomberg BusinessWeek, The Atlantic, The Nation, Fortune, and Politico.