Weird Short Story Writers for Strange Times

Jason Ockert on Authors That Engage the Unexpected

Weird is difficult to define. A cousin of strange, it tends to make us feel slightly uncomfortable. And yet, over time abnormal can be rendered normal and the unfamiliar made familiar. It wasn’t common to wear a face mask three years ago and, depending on where you live, it’s the new normal now. As a species, we adapt in order to endure. But as individuals we carry unique thoughts and feelings and respond to the world according to our own understanding of it.

Weird, like strange, is in the eye of the beholder. All of us have built in WTF barometers which we apply to the infinite flow of stimuli bombarding our eyeballs. We live our lives in medias res and the whir of WTF can lock us in a state of anxiety. Who knows what’s coming next? Not me, but I suspect it’s not good. My lack of control over what tomorrow will bring makes me jittery. When the creeping sense of dread becomes too much, I read short stories. At the very least, I know that there will be an ending and it is coming soon.

Weird short stories are gifts from strangers. After you’ve torn away the wrapper and set the curiously odd item on the table you might say, “WTF is this?” It’s nothing you asked for but maybe something you need. It captures your attention. Sure, you don’t understand what you’re supposed to do with it but it’s better than another scented candle. Luckily, your gift comes with an instruction manual. And if you pay attention, take your time, and keep yourself open to the possibility of discovery, it may prove to be the best present you’ve ever received.

Here are four writers who write weird wonderfully:

Steven Millhauser

Steven Millhauser is my favorite living short story writer. He is as close as we get to a real-life wizard. He writes with Houdini-hands and I find myself enchanted by his stories.

To anyone who has never encountered a Millhauser story, I recommend his collected works, We Others. These new and selected stories span over 30 years. In addition to several new stories included in the book, there are stories from In the Penny Arcade, The Barnum Museum, The Knife Thrower, and Dangerous Laughter. Once you’ve read the sample stories from his earlier work I highly suggest you go back and read the rest.

Millhauser’s stories almost always disorient right off the bat. The first story in We Others is called “The Slap.” The piece opens when a man, Walter Lasher, is approached by a stranger in a parking lot and is slapped hard in the face. The attack is, apparently, unprovoked and a random act of violence. From the onset, we have some questions: What did Walter do to deserve this? How is he going to respond to the attack? Who is the Slapper?

In these stories, aliens are landing, ghosts are narrating, the art of magic is alive, a knife thrower comes to town, and yes, characters are slapped in the face. Shocking a reader at the beginning of a story as a means of tricking them onto the page is not difficult. The hard part is to coax the reader along—sentence by sentence—and the greatness of Millhauser’s work is not in its disorientation but in the way that he re-orients you. “The Slap,” for example, is a pattern story. This style of story takes advantage of escalation—first Walter Lasher is slapped, then Robert Sutliff is slapped, then Charles Kraus is slapped!—until the strangeness of getting slapped feels familiar. In fact, a reader starts to wonder why more people aren’t getting slapped.

The stories I love do not have happy endings.

Of course, a pattern story that is simply an escalation of the central routine is unremarkable. The pattern must break. We demand answers to the questions that the writer made us ask in the beginning. And the answers must be right. If the answers are predictable—something we expected all along—we’re disappointed. If the answers are too vague or confusing, we’re angry. Millhauser’s answers proceed from the logic of the story and they are always satisfying. Once we’ve been slapped by a Millhauser story we cannot be un-slapped.

Karen Russell

Short story writers understand the beauty of compression. And they also realize that every single word that appears after the first sentence is feverishly moving to the end. If a writer does not provide the perfect ending, the rest of the story risks being forgotten. For me, Karen Russell is a literary gymnast who knows just how to stick the landing.

In each of the stories in Russell’s collections (St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves, Vampires in the Lemon Garden, and Orange World), the characters become the stabilizing epicenter for the weird. Yes, the girls are wolves. Yes, there is a vampire in the lemon grove. Yes, there’s a demon in the gutter outside the window. These things are true in the world of a Karen Russell story. But what brings me back to these pieces time and again is the perseverance of the protagonists. They are wounded, but they’re not victims. They’re turned around, not lost. They’ve been shoved off a cliff but their fingernails are still clutching the edge. We empathize with their vulnerabilities and root for them to somehow overcome their seemingly-doomed circumstances.

My favorite endings provide the reader with an image or a gesture. The protagonist performs one final act—returns to the pack, faces the monster in the mirror, calls Mom. We mull over what the gesture means for the character and in doing so we clarify what it means to us. That’s how the dream of the story lives on in our imaginations.

Ted Chiang

What I admire most about Ted Chiang’s short story collections (Stories of Your Life and Others and Exhalation) is his ability to supply his narratives with galaxy-sized concepts within the confines of a tea kettle. He does this by always turning the lens inward, delving deeper into the nuances of humanity despite the oddities of the humans.

The titular story in Exhalation, told in an epistolary style, finds the first person narrator contemplating how life will end. Chiang’s choice of format is brilliant—letters are, after all, artifacts, and tangible items that can be examined. By taking a notion that cannot easily be described (the end of life) and inserting it into a confined space (a letter), the form itself counterbalances the conceit. Chiang is invested in the journey toward discovery and he never leaves the reader behind. “Exhalation” is pitch-perfect, ruminative, and surprising. The piece is not a heavy-handed doomsday warning; it is a reminder to persist even as the clock winds down.

Brian Evenson

Brian Evenson is the king of literary horror. The collections I recommend are Collapse of Horses, Song for the Unraveling of the World, and The Glassy, Burning Floor of Hell.

Evenson’s stories are uncanny, like being in a store—masked up—and seeing someone who looks vaguely familiar. You can’t quite identify the person, so you follow them into the parking lot and watch them get into a car that looks like yours. For a split second you wonder if you’re being robbed. But, no, your car is a few rows over and as you drive, distracted, you wonder who that was. When you get home you find the person in your living room sitting in your chair. Unmasked, they look exactly like you. But when you tear off your own mask to confront the stranger you discover that your face has changed. You’re not who you thought you were at all. In fact, you might be the intruder.

The act of reading is intimate and the best stories read like they were written specifically for us. One way a writer can latch onto a reader is to unsettle them. Evenson’s work isn’t scary—it’s psychologically terrifying. He disrupts our expectations and retrains our attention on the fringe. My favorite piece from his most recent collection, The Glassy, Burning Floor of Hell, is “The Shimmering Wall.” The story begins this way: “Those parts of the domed city were not the city at all—or maybe the parts we lived in were what was not the city.” WTF, right? We are being invited into the land of Evenson and it’s a thrilling place to reside.

*

The stories I love do not have happy endings. A happy ending is like fluorescent lighting at a grocery store where all of the carefully-designed products are illuminated and ready to be consumed—an unsettling sight. Nor am I in the mood for stories that pitch me into a bottomless pit of despair and hopelessness. I get enough of that from the news.

The pieces I love seem strange at first. They are gifts I don’t think I need. Gradually, though, the weird wears off and you discover that what the writer has given you is a matchstick. The world is filled with dark places and stories equip us with the possibility of providing light. Look around. Strike anywhere.

__________________________________

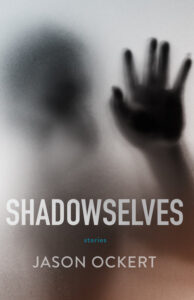

Shadowselves by Jason Ockert is available via Dzanc Books.

Jason Ockert

Jason Ockert is the author of Wasp Box, a novel, and three collections of short stories: Shadowselves, Neighbors of Nothing, and Rabbit Punches. Winner of the Dzanc Short Story Collection Contest, the Atlantic Monthly Fiction Contest, and the Mary Roberts Rinehart Award, he was also a finalist for the Shirley Jackson Award and the Million Writers Award. His work has appeared in journals and anthologies including Best American Mystery Stories, Granta, The Cincinnati Review, Oxford American, One Story, and McSweeney’s. He teaches at Coastal Carolina University.