The objective of NASA’s Apollo Program (1963-1972) was to land humans on the Moon and bring them safely back to Earth. Six of the missions accomplished this goal, completing the 238,900-mile return trip with a wealth of scientific data and more than 842 pounds of lunar rock and debris specimens. During the missions, a total of 304 hours were spent on the Moon’s surface and nearly 20,000 photographs were taken.

The astronauts documented their reconnaissance of sublime lunar landscapes, specific geological features, their own scheduled activities and dozens of experiments. Among other photographic equipment, specially designed 70mm Hasselblad cameras were developed and modified for the missions. By the time Apollo 17, the final mission, returned to Earth in 1972, twelve of these cameras had been abandoned on the Moon in order to make room for collected rocks and specimens. Only one, from Apollo 15, was returned to Earth. It recently sold at auction for more than $900,000.

The astronauts documented their reconnaissance of sublime lunar landscapes, specific geological features, their own scheduled activities and dozens of experiments. Among other photographic equipment, specially designed 70mm Hasselblad cameras were developed and modified for the missions. By the time Apollo 17, the final mission, returned to Earth in 1972, twelve of these cameras had been abandoned on the Moon in order to make room for collected rocks and specimens. Only one, from Apollo 15, was returned to Earth. It recently sold at auction for more than $900,000.

Prior to their missions, all of the Apollo astronauts trained extensively with the sophisticated Hasselblads, taking hundreds of photographs in challenging real and simulated settings in order to familiarize themselves with the technology. They were even encouraged to take the cameras on family trips.

Once they reached the Moon, the astronauts wandered like tourists, photographing “targets of opportunity” and whatever else they found interesting or dramatic. The most iconic images have become part of our collective human memory.

While on the lunar surface, the astronauts often wore cameras mounted on brackets attached to the chests of their space suits. These provided support and relative ease of operation, leaving hands free. The lunar surface cameras did not have viewfinders, light meters or automatic exposure and focus controls. Exposure settings for a variety of anticipated conditions were determined in advance, and guidelines were printed on top of the film magazines. Shutter speeds were typically set at 1/250 and f -stop recommendations were f/5.6 for objects in shadow; f/11 for sun. Instead of a rotating variable focus ring, the cameras had three settings: near, medium and far. A similar “zone” focusing system was used on some consumer compact cameras of the period.

The lunar surface cameras were fitted with Réseau plates, clear glass panes etched with a precise pattern of crosshairs, which would allow analysts to correct for image distortion and calibrate distance and heights, both on the Moon’s surface and from space. Many of the images produced with this technology were later assembled into David Hockney-like panoramic collages that present deep, accurate views of the expansive lunar landscape.

The photographs that appear here are from Kipp Teague’s exhaustive independent Project Apollo Archive, released in 2015 and developed with assistance from NASA, the Johnson Space Center and Eric M. Jones’ Apollo Lunar Surface Journal.

Although the astronauts’ task was simply to document their activities and strange surroundings, many of the images have unintended artful compositions. “Sunstruck” tonal shifts and in-camera cropping only enhance their unconscious aesthetic and beautiful, deft outtake quality.

–Evan Backes and Tom Adler

Astronaut Russell “Rusty” L. Schweickart outside Command Module “Gumdrop” in Earth’s orbit. [Apollo 9]

Astronaut Russell “Rusty” L. Schweickart outside Command Module “Gumdrop” in Earth’s orbit. [Apollo 9] Astronaut David Scott standing in the open hatch of the Command Module. Rusty Schweickart took this photograph from the porch of the Lunar Module “Spider.” [Apollo 9]

Astronaut David Scott standing in the open hatch of the Command Module. Rusty Schweickart took this photograph from the porch of the Lunar Module “Spider.” [Apollo 9] Buzz Aldrin’s “Bootprint Penetration Experiment” to study soil mechanics. Aldrin removed his camera from the chest-mounted bracket to get a closer view. [Apollo 11]

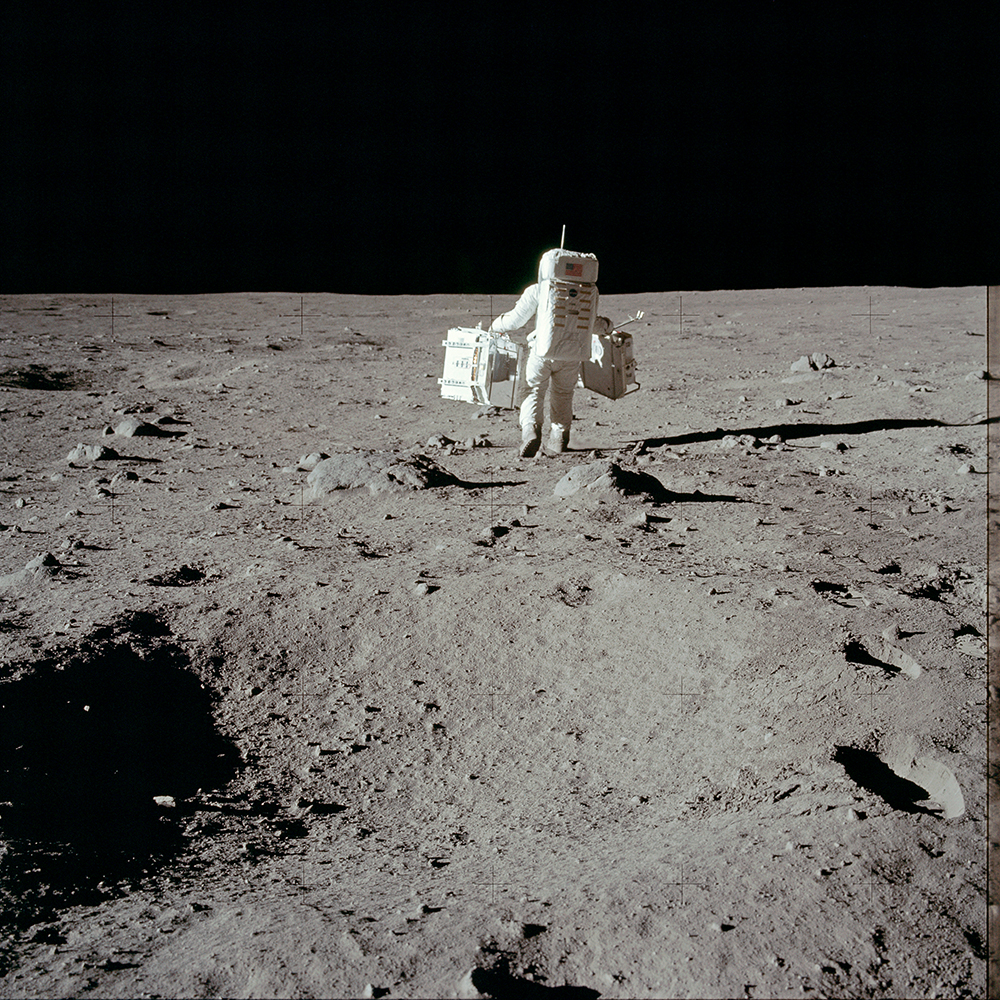

Buzz Aldrin’s “Bootprint Penetration Experiment” to study soil mechanics. Aldrin removed his camera from the chest-mounted bracket to get a closer view. [Apollo 11] Buzz Aldrin carries the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package. Photo by Neil Armstrong. [Apollo 11]

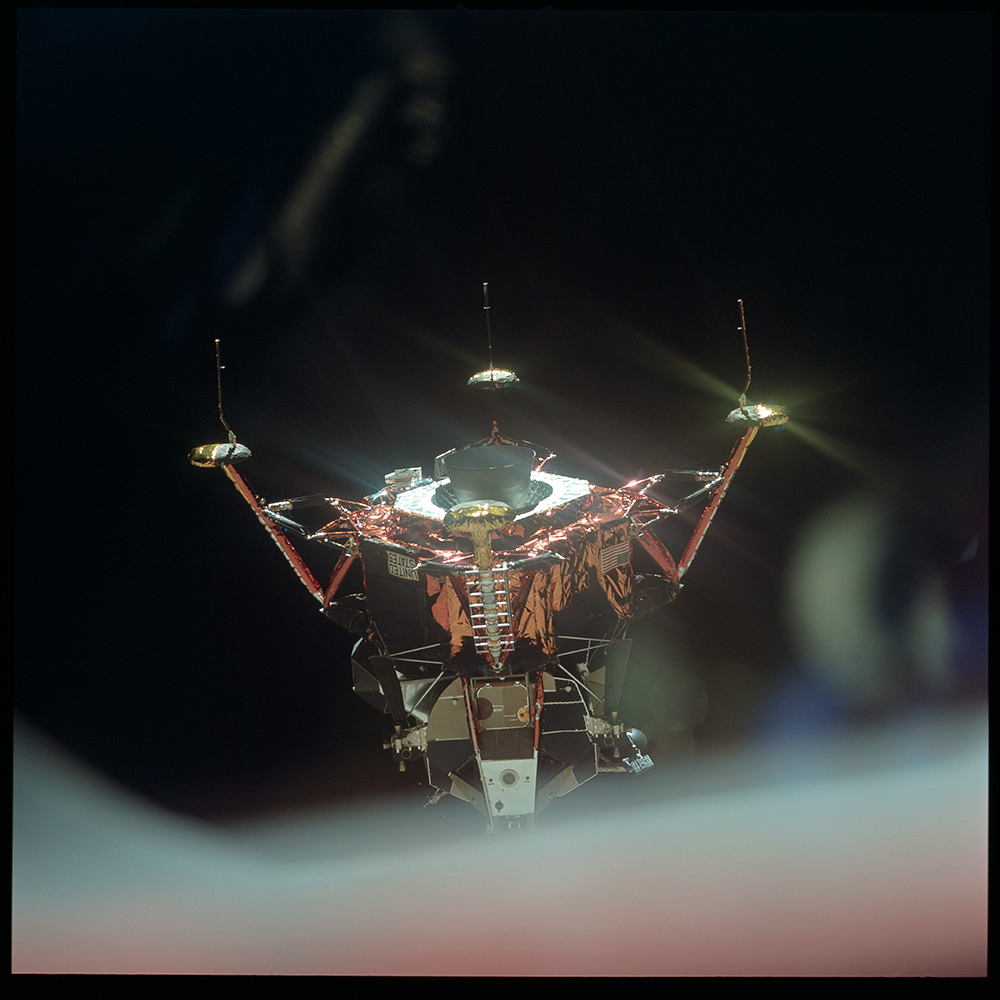

Buzz Aldrin carries the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package. Photo by Neil Armstrong. [Apollo 11] Lunar Module “Eagle” carrying Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin after undocking from the Command Module “Columbia.” Photo by Michael Collins. [Apollo 11]

Lunar Module “Eagle” carrying Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin after undocking from the Command Module “Columbia.” Photo by Michael Collins. [Apollo 11] Charles “Pete” Conrad, Jr. with 70mm camera and extension handle. Photo by Alan Bean. [Apollo 12]

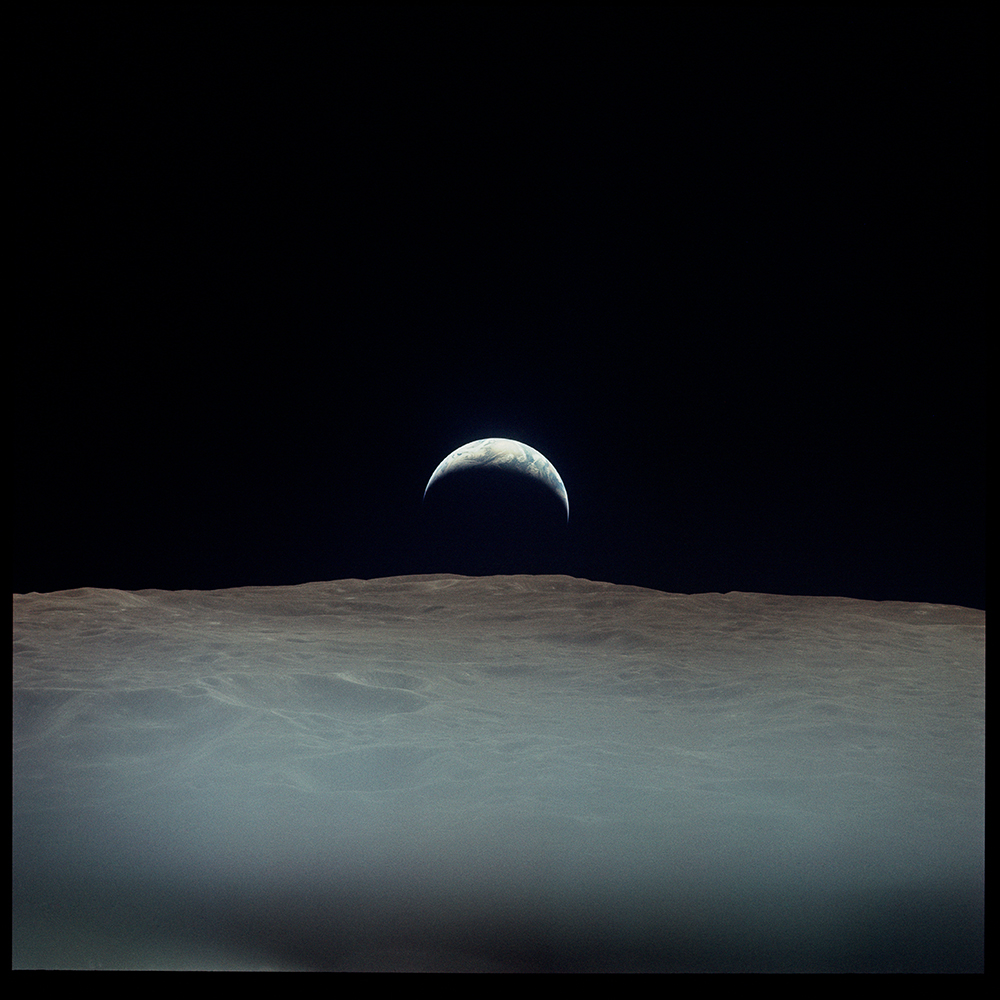

Charles “Pete” Conrad, Jr. with 70mm camera and extension handle. Photo by Alan Bean. [Apollo 12] Earth rises above the horizon. Photo by Richard Gordon. [Apollo 12]

Earth rises above the horizon. Photo by Richard Gordon. [Apollo 12] Commander Alan Shepard shades his eyes from the sun after his first steps on the Moon. Photo by Edgar Mitchell. [Apollo 14]

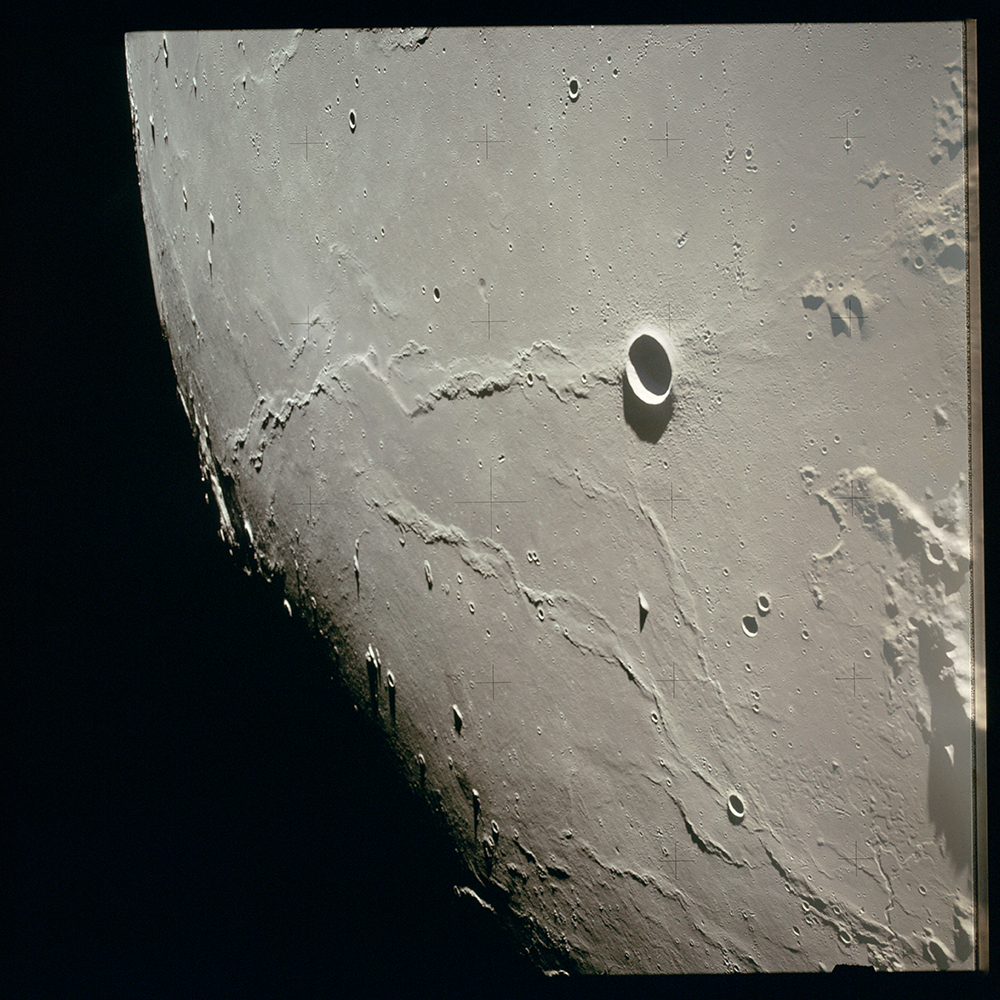

Commander Alan Shepard shades his eyes from the sun after his first steps on the Moon. Photo by Edgar Mitchell. [Apollo 14] Nielsen crater and the Ocean of Storms from the Command Module “Endeavour.” Photo by Alfred M. Worden. [Apollo 15]

Nielsen crater and the Ocean of Storms from the Command Module “Endeavour.” Photo by Alfred M. Worden. [Apollo 15] American flag alongside the Solar Wind Composition Experiment. Photo by Charlie Duke. [Apollo 16]

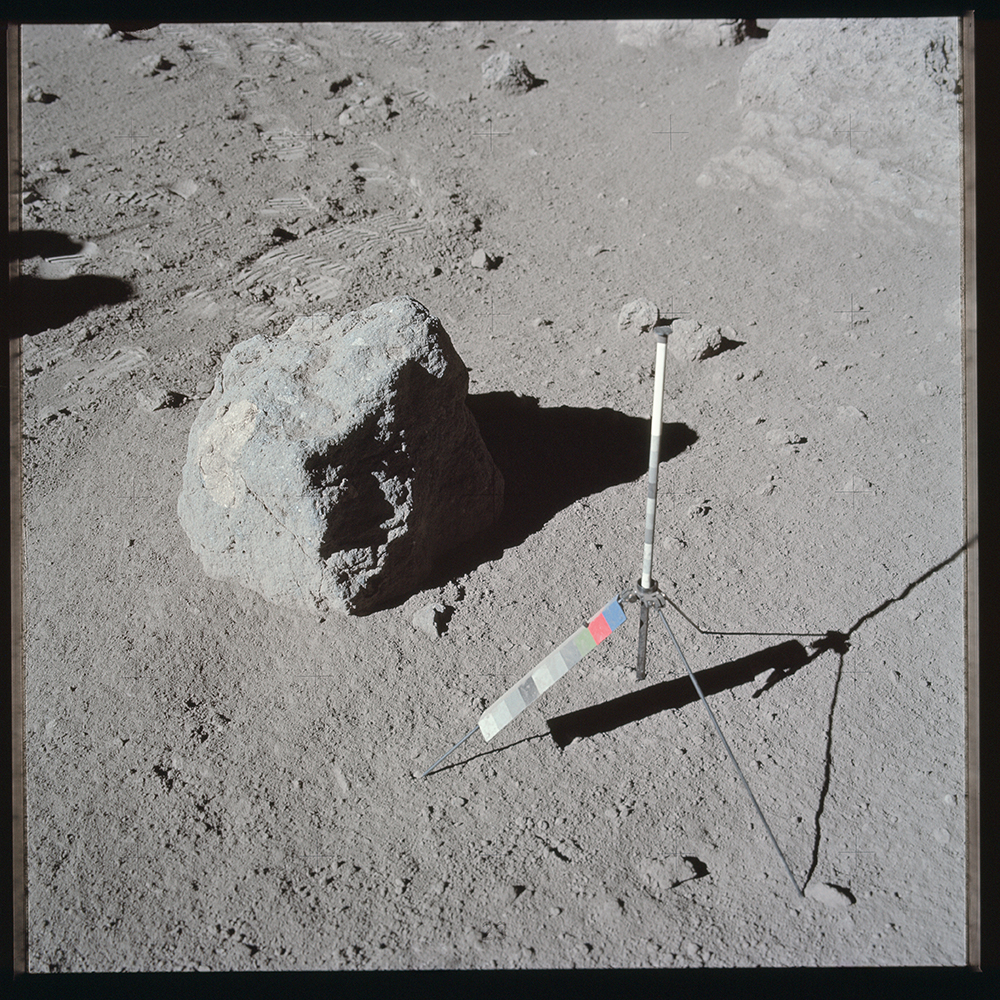

American flag alongside the Solar Wind Composition Experiment. Photo by Charlie Duke. [Apollo 16] A gnomon with color patch used to indicate sun angle, scale and lunar color. Photo by Gene Cernan. [Apollo 17]

A gnomon with color patch used to indicate sun angle, scale and lunar color. Photo by Gene Cernan. [Apollo 17] Scientist-astronaut Harrison Schmitt heading back to the rover with sampling scoop in hand. East Massif (left) and Bear Mountain (center right) are behind him. This is one of the last photographs taken of man on the Moon. Photo by Gene Cernan. [Apollo 17]

Scientist-astronaut Harrison Schmitt heading back to the rover with sampling scoop in hand. East Massif (left) and Bear Mountain (center right) are behind him. This is one of the last photographs taken of man on the Moon. Photo by Gene Cernan. [Apollo 17]

From The Moon 1968-1972. Edited by Evan Backes & Tom Adler. Used with permission from T. Adler Books, Santa Barbara.

Lit Hub Photography

Photography excerpts are curated by Catherine Talese and Rachel Cobb.